The young woman shook her head, urgent and forceful, and her eyes grew darker, their pale summer-blue colour changing as if someone had spilled a droplet of ink into each one. Just as the whistle touched his lips she gave a strange little shudder and moved her hand quickly. He thought at first it was to snatch the whistle from him, but instead it went to the blouse buttons at her throat and started to undo them. Pyotr watched. As each button revealed more, he felt the blood rush to his face, burning his cheeks.

Her skin was like milk. White and unused below the golden triangle at her neck where the sun had crept in. The blouse was shapeless, collarless, with short embroidered sleeves and, though it may once have possessed colour, now it was bleached to the grey of ash. As she slid the blouse open, he caught the flash of a knife at her waistband. It gave him a shock. Underneath the blouse she was wearing only a flimsy garment of threadbare material that clung to her thin body. The sight of her fragile collarbones made him forget the whistle, but it was her breasts he stared at, where the cloth outlined them clearly. His brain told him he should look away but his eyes took no notice.

Then once more she pressed a finger to her lips and gave him a smile that, in a strange way he didn’t understand, seemed to steal something from inside him. It left a hole in a secret place, which previously only his mother had touched – and that was when he was just a child. His chest stung so badly he had to crush his hand against his ribs to stop the hurt, and by the time he looked back, she was gone. A faint movement of the branches and a shimmer of leaves, that was all that remained. Even the wolf had disappeared.

He stayed there with the whistle in his hand for what felt like for ever but which must have been no more than a minute, and gradually the sounds around him started to return. The dog whining; the hunters calling and cursing him. A magpie rattled out its annoyance. He knew he should shout to them, it was his duty as a Soviet citizen to alert them. Quick, there’s a fugitive running down to the river. Bring your rifle. But something stubborn hardened inside his young chest when he thought of the moonlight hair, and the words wouldn’t come to his lips.

7

Sofia stood without moving, concentrating on the sounds of the night: the rustle of some small creature as it skittered over a tree stump; a faint plop in the water, most likely a toad. Above her the sky was as black as she could wish for, a warm summer night with the air moist on her skin and no sign of the wolf. She’d seen the animal skulking around yesterday, its festering paw thick with summer flies, so she knew it posed no threat to her or the boy. It just wanted somewhere to hide and lick its wound. No sign of the dog or the men either.

Were they listening for her, as silently as she was listening for them? Here among the whisper of the trees. The silence a trap for me?

But no, OGPU troops didn’t possess that kind of patience. They liked to storm in at night and yank you from your bed when you were soft and vulnerable and at your weakest. Not this silent soulless stalking. No. Whoever the men with the rifles were, they weren’t the secret police.

She felt her pulse drop a notch and began to breathe more easily. Her feet made no sound as she wove between the trees, heading for the cabin, the pine needles releasing their fragrance under her feet. Hunters, that’s what they must have been, with their hound on the scent of… what? The wolf, probably. Already back in their village with a glass of kvass and a hand groping the skirts of a willing wife while-

Someone was in the clearing.

A dim light spilled from the hut and cut a yellow wedge out of the darkness, revealing a horse tethered outside. Sofia’s heart stopped. She shrank back into the trees and merged with one of the black pine trunks, the length of her body tight against its rough bark. It smelled strongly of resin. She wanted to smell of resin too, to hide her scent in the skin of the tree. The light went out and instantly the cabin door opened, figures emerged. The horse whinnied a welcome and she heard two male voices speak in low whispers. Then came the excited bark of a hound and the creak of saddle leather as one of the men swung up on to the horse. There was the shake of a bridle, the impatient stamp of hooves.

‘Thank you, my friend,’ one man said, his voice unsteady with some strong emotion. ‘I… can say no more… but spasibo. Thank you.’

Sofia caught the flat sound of two hands being clasped, then the horse cantered away across the clearing, heading west. It was in a hurry. She listened for the other man and his dog but they seemed to have vanished into the night. She told herself that whoever he was, he was nothing to her, just a temporary disturbance of her own night’s plans. She could still make it down to Tivil village before dawn.

She released her hold on the tree and felt a tremor of anticipation tighten her skin. With a stealth and sureness that were gained from months of travelling by night, she slid away into the blackness.

She had picked her time well. Still a couple of hours till dawn, the villagers had not yet begun to stir from the warmth of their beds.

The village of Tivil lay silent in the darkness. It looked crumpled and lifeless, yet Sofia’s heart lifted at the sight of it. This was the place she’d spent months searching for. She’d pictured it a thousand times in her mind, sometimes bigger, sometimes smaller, but always with one person standing at the heart of it.

Vasily. Now she had to find him.

Her pulse quickened as she stared down into the valley from the forest ridge. Again into her mind sprang the question that had plagued her steps each time she’d risked her life sneaking into barns or thieving chicken eggs to survive. Was Tivil the right place? Or had she come all this way for nothing? She shivered at the thought and pushed it away out of reach, because she had staked everything on one woman’s word. That woman was Maria, Anna’s childhood governess.

How good was her word?

Maria had whispered to Anna when she was arrested that Vasily had fled from Petrograd after the 1917 Revolution and turned up on the other side of Russia in Tivil, living under the name of Mikhail Pashin.

But how good was her word?

Sofia had to believe he was here, had to know he was close.

‘Vasily,’ she whispered aloud into the wind so that it would carry the word down to the houses below, ‘I need your help.’

She slid down from the ridge with a soundless tread. The only movements along Tivil’s dirt road were the brief flickers of shadow as clouds traced a path across the face of the moon, emerging now from its sleep. She had observed the izbas carefully, the rough single-storey houses that clung to the edge of the road, with their intricate shutters and precious patches of land staked out behind them in long rectangles. She watched till her eyes ached, trying to prise dark shapes out of a dark landscape. But nothing ruffled the stillness.

That’s when she drew the knife from the rawhide pouch on her hip and finally, after so many months of effort, set foot in Tivil. It gave her a quick and unexpected surge of joy and she felt her damaged fingertips tingle. The village was made up of a straggle of houses each side of a single central street, mixed up with an untidy jumble of barns and stables and patched fences. It lay at the head of the Tiva valley which, further down, shook itself loose and broadened into a wide plain protected by steep wooded ridges where hawks cruised by day.

At the centre of the village stood the church. Now that in itself was strange. Throughout Russia most village churches had been blown up by order of the Politburo or were being used as storage for grain or manure – the ultimate insult. This one had escaped such shame but, judging by the abundance of notices pinned outside, it had been turned into a general assembly hall for the compulsory political meetings. The brick building loomed deeper black against the black sky, almost as much a presence as the forest itself, and it gave Sofia hope.

Maybe Maria was as good as her word. It could be true – all of it. But just because the church was here, she told herself, that didn’t mean Vasily was, or that he’d be crazy enough to want to risk his life on the word of a stranger.

She moved with the shadows into the doorway of the church. Chyort! The lock was a big old-fashioned iron contraption that would shrug off any attempts she made with her knife. With another muttered oath she skirted round the side of the building, all the time scanning for any movement in the darkness. At the back, where the fields crept close to a scrubby yard, she found a small door, its lock flimsier. Immediately she set about it with the tip of her blade.

Sofia worked quickly, concentrating hard, careful to keep the sound low, but her pulse missed a beat when the shadows abruptly grew paler around her. A light must have been turned on somewhere close. She edged stealthily back to the corner of the building, her body becoming part of its solid mass, and holding her breath she peered into the street.

The solitary light gleamed out at her like a warning. It came from the window of a nearby izba. And as she watched, a man crossed inside the rectangle of yellow lamplight, a tall figure moving in a hurry, and then he was gone. A moment later the izba was plunged once more into darkness and the sound of a front door shutting reached her ears.

What was he doing out so early? She hadn’t bargained on the village coming to life before dawn. Didn’t he sleep? A bat darted across her line of vision, making her jerk away awkwardly. Her hair felt slick on the back of her neck. The man’s footfalls sounded as clear as her own heartbeat in her ears and, watching from her hiding spot, she saw the figure pass. His determined stride and speed of movement made Sofia nervous, but still she crept forward to see more.

He was heading away from her down the street, picked out in detail by a brief trick of the moon. It allowed her to make out that his hair was clipped short and he was wearing a rough workman’s shirt, which struck her as odd because he moved with the easy assurance and confidence of someone who was used to a position of command. Sofia’s hand relaxed on the knife.

Could it be Vasily?

She almost stepped out into the street and called his name. Except of course it wouldn’t be the name she knew, it would be Mikhail Pashin, the name Anna had said he was using. ‘Mikhail Pashin,’ she whispered, but too softly for anything but the moon to hear. She struggled to subdue a wave of excitement and reined in an unruly surge of hope. Surely she couldn’t be so lucky? She scuttled along the front of the church and, as she peered out into the shadows that were wrapped round the village, her luck held and the moon gave up its flirting behind the clouds and emerged white and full, bathing the street in solid silver.

He was there, ahead of her, clearly outlined, moonlight robbing him of colour, so that he could have been a ghost. A ghost from the past. Is that what you are, Mikhail Pashin?

She saw him turn off the street up a steep rutted track that clung to the hillside, leading up to the vague outline of a long dark building, a form she could only just make out. She was tempted to follow his footsteps but something about him made her certain she would be discovered. There was an alertness about him that, even in the dim light, came off him like sparks.

She sank to the ground, waiting, invisible in the black overhang of the church, her back pressed firmly against the wall to keep her still. Her patience was rewarded ten minutes later when she heard the sound of a horse descending the track, its hooves lively on the dry earth. She exhaled with relief because the rider was the same man. He’d obviously been up to a stable and saddled his horse for an early morning start, his cropped hair and broad shoulders painted silver by the moonlight once again.

But to her surprise, behind him a man on foot was also trotting down the track, a small slight figure, middle-aged but very light on his feet. They were talking in low voices but there was a certain curtness in their manner towards each other that spoke of ill feeling. Sofia’s gaze remained fixed on the rider.

Anna. Her lips didn’t move but the words sounded sharp as ice in her head. I think I’ve found Mikhail Pashin.

Just then the two men reached the point where the rutted track joined the road, and the rider turned abruptly to the left without a word. The second man, the small one, turned right, but not before he had run the palm of his hand lovingly down the massive curve of the horse’s rump as it swung away from him. Then, with his shoulders lifting and falling repeatedly, as if he was trying to uncage a painful tension in his neck, he stood staring after the horse and man.

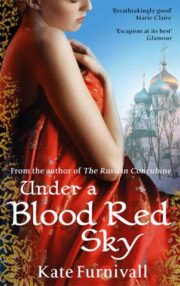

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.