She was lying on the pillow, lit only by a single candle and by the flickering light from the fire. She had unbraided her hair and it spread dark and sweet-smelling on the pillow. A sudden anguish of longing for his lost wife Jane, and the serious passionate desire that they had shared, swept over John. He had promised himself he would not think of her, he had thought it would be fatal to this night if he thought of her, but when he saw Hester in his bed, he did not feel like a bridegroom, but like an unwilling adulterer.

It was a business contract, and it must be fulfilled. John turned his mind to the outrageously half-naked painted women of the old king’s court. He had seen them at New Hall when he was little more than a boy and remembered them still with an erotic mixture of disapproval and desire. He held the thought of them in his mind and moved toward Hester.

She had never been touched by a man who was in love with her, or she would have known at once that John was offering her the false coin of his body while his mind was elsewhere. But she too knew that the contract of marriage was not completed until consummation. She lay still and helpful beneath him while he pierced her and then brutally moved in the wound. She did not complain, she did not comment. She lay in silence while the pain went on and then suddenly stopped as he sighed and then moved away from her.

She rose up, biting her lip against the hurt, and wrapped a cloth tightly around her groin. There was only a little blood, she thought; it probably felt worse than it was. She thought that she would have taken the whole thing easier if she had been younger, fresher, warmer. It had been a coldhearted assault and a coldhearted acceptance. She shivered in the darkness and got back into bed beside her husband.

John had turned to lie on his side with his back to her as if he would shut out the sight of her and shut out the thought of her. Hester crept back under the covers, careful not to touch him, not to breach the space between them, and set her teeth against the pain, and against the bitterness of disappointment. She did not cry, she lay very still and dry-eyed and waited for the morning when her married life would begin.

“I shall go to Oatlands this week,” John remarked the very next morning at breakfast. Hester, seated beside Baby John, looked up in surprise. “This week?”

He met her gaze with bland incomprehension. “Yes.”

“So soon?”

“Why not?”

A dozen reasons why a newlywed husband should not leave his home in the first week of his marriage came to her. She folded her lips tightly on them. “People may think it looks odd” was all that she said.

“They can think what they like,” John retorted bluntly. “We married so that I should be free to do my work and that is what I am doing.”

Hester glanced at Frances, seated at her left, opposite Baby John. Frances’s white-capped head was bowed over her bowl, she did not look up at her father, she affected to be deaf.

“There is the planting of the spring bulbs to finish,” he said. “And pruning, and planning for winter. I have to make sure the silkworm house is sound against the weather. I shall be a month or so away. If you are in any need you can send for me.”

Hester bowed her head. John rose from his place and went to the door. “I shall be in the orchard,” he said. “Please pack my clothes for me to go to Oatlands and tell the boy I shall want a horse this afternoon. I shall ride down to the docks and see if anything has come in for the king’s collection.”

Hester nodded and she and the two children sat in silence until the door closed behind John.

Frances looked up, her lower lip turned down. “I thought he would stay home all the time now you are married.”

“Never mind!” Hester said with assumed cheerfulness. “We’ll have lots to do. There’s a bonfire to build for Guy Fawkes’s day, and then Christmas to prepare for.”

“But I thought he would stay home,” Frances persisted. “He will come home for Christmas, won’t he?”

“Of course,” Hester said easily. “Of course he will. But he has to go and work for the queen in her lovely gardens. He’s a royal gardener! He can’t stay home all the time.”

Baby John looked up and wiped his milky mustache on his sleeve.

“Use your napkin,” Hester corrected him.

Baby John grinned. “I shall go to Oatrands,” he said firmly. “Pranting and pranning and pruning. I shall go.”

“Certainly,” Hester said, and she emphasized the correct pronunciation: “Planting and planning and pruning are most important.”

Baby John nodded with dignity. “Now I shall go and look at my warities.”

“Can I take the money from the visitors?” Frances asked.

Hester glanced at the clock standing in the corner of the room. It was not yet nine. “They won’t come for another hour or so,” she said. “You can fetch your schoolwork, both of you, for an hour, and then you can work in the rarities room.”

“Oh, Hester!” Frances complained.

Hester shook her head and started to pile up the empty porridge bowls and the spoons. “Books first,” she said. “And, Baby John, I want to see all our names written fair in your copybook.”

“And then I will go pranting,” he said.

Hester packed John’s clothes for him and added a few jars of bottled summer fruit to the hamper that would follow him by wagon. She was up early on the day of his departure to see him ride away from the Ark.

“You had no need to rise,” John said awkwardly.

“Of course I had need. I am your wife.”

He turned and tightened the girth on his big bay cob to avoid speaking. They were both aware that since the first night they had not made love, and now he was going away for an indefinite period.

“Please take care at court,” Hester said gently. “These are difficult times for men of principle.”

“I must say what I believe if I am asked,” John said. “I don’t venture it, but I won’t deny it.”

She hesitated. “You need not deny your beliefs but you could say nothing and avoid the topic altogether,” she suggested. “The queen especially is touchy about her religion. She holds to her Papist faith, and the king inclines more and more to her. And now that he is trying to impose Archbishop Laud’s prayer book on Scotland, this is not a time for any Independent thinker; be he Baptist or Presbyterian.”

“You wish to advise me?” he asked with a hint of warning in his voice which reminded her that a wife was always in second place to a man.

“I know the court,” she said steadily. “I spent my girlhood there. My uncle is an official painter there, still. I have half a dozen cousins and friends who write to me. I do know things, husband. I know that it is no place for a man who thinks for himself.”

“They’re hardly likely to care what their gardener thinks,” John scoffed. “An undergardener at that. I’ve not even been appointed to my father’s post yet.”

She hesitated. “They care so much that they threw Archie the jester out with his jacket pulled over his head for merely joking about Archbishop Laud; and Archie was the queen’s great favorite. They certainly care what you think. They are taking it upon themselves to care what every single man, woman, and child thinks. That’s what the very quarrel is all about. About what every individual thinks in his private heart. That’s why every single Scotsman has to sign his own covenant with the king and swear to use the Archbishop’s prayer book. They care precisely what every single man thinks.” She paused. “They may indeed question you, John; and you have to have an answer ready that will satisfy them.”

“I have a right to speak to my God in my own way!” John insisted stubbornly. “I don’t need to recite by rote, I am not a child. I don’t need a priest to dictate my prayers. I certainly don’t need a bishop puffed up with pride and wealth to tell me what I think. I can speak to God direct when I am planting His seeds in the garden and picking His fruit from His trees. And He speaks to me then. And I honor Him then.

“I use the prayer book well enough – but I don’t believe that those are the only words that God hears. And I don’t believe that the only men God attends are bishops wrapped up in surplices, and I don’t believe that God made Charles king, and that service to the king is one and the same as service to God. And Jane-” He broke off, suddenly aware that he should not speak to his new wife of his constant continuing love for her predecessor.

“Go on,” Hester said.

“Jane’s faith never wavered, not even when she was dying in pain,” John said. “She would never have denied her belief that God spoke simple and clear to her and she could speak to Him. She would have died for that belief, if she had been called to do so. And for her sake, if for nothing else, I will not deny my faith.”

“And what about her children?” Hester asked. “D’you think she would want you to die for her faith and leave her children orphans?”

John checked. “It won’t come to that.”

“When I was at Oatlands only six months ago, the talk was all about each man’s faith and how far each man would go. If the king insists on the Scots following the prayer book he is bound to insist on it in England too. If he goes to war with the Scots to make them do as he bids, and some say he might do that, who can doubt that he will do the same in England?”

John shook his head. “This is nothing,” he said. “Nonsense and heartache about nothing.”

“It is not nothing. I am warning you,” Hester said steadily. “No one knows how far the king will go when he has to protect the queen and her faith, and to conceal his own backsliding toward popery. No one knows how far he will go to make everyone conform to the same church. He has taken it into his head that one church will make one nation, and that he can hold one nation in the palm of his hand and govern without a word to anyone. If you insist on your faith at the same time as the king is insisting on his, you cannot say what trouble you might be running toward.”

John thought for a moment and then he nodded. “You may be right,” he said reluctantly. “You are a powerfully cautious woman, Hester.”

“You have given me a task and I shall do it,” she said, unsmiling. “You have given me the task of bringing up your children and being a wife to you. I have no wish to be a widow. I have no wish to bring up orphans.”

“But I will not compromise my faith,” he warned her.

“Just don’t flaunt it.”

The horse was ready. John tied his cape tightly at the neck and set his hat on his head. He paused; he did not know how he should say farewell to this new, common sense wife of his. To his surprise she put out her hand, as a man would do, and shook his hand as if she were his friend.

John felt oddly warmed by the frankness of the gesture. He smiled at her, led the horse over to the mounting block and got up into the saddle.

“I don’t know what state the gardens will be in,” he remarked.

“For sure, they will appoint you in your father’s place when you are back at court,” Hester said. “It was only your absence which made them delay. It is out of sight, at once forgotten with them. When you return they will insist on your service again.”

He nodded. “I hope they have not mistook my orders while I was gone. If you leave a garden for a season it slips back a year.”

Hester stepped forward and patted the horse’s neck. “The children will miss you,” she said. “May I tell them when you will be home?”

“By November,” he promised.

She stepped back from the horse’s head and let him go. He smiled at her as he passed out of the stable yard and ’round the path which led to the gate. As he rode out he had a sudden sense of joyful freedom – that he could ride away from his home or ride back to it and that everything would be managed without him. This was his father’s last gift to him – his father who had also married a woman who could manage well in his absence. John turned in his saddle and waved at Hester who was still standing at the corner of the yard where she could look after him.

John waved his whip and turned the horse toward Lambeth and the ferry. Hester watched him go and then turned back to the house.

The court was due at Oatlands in late October, so John was busy as soon as he arrived planting and preparing the courts that were enclosed by the royal apartments. The knot gardens always looked well in winter, the sharp geometric shapes of the low box hedging looked wonderful thinned and whitened by frost. In the fountain court John kept the water flowing at the slowest speed so that there would be a chance for it to make icicles and ice cascades in the colder nights. The herbs still looked well, the angelica and sage went into white lace when the frost touched their feathery fronds behind the severe hedging. Against the walls of the king’s court John was training one of his new plants introduced from the Ark: his Virginian winter-flowering jasmine. On warm days its scent drifted up to the open windows above, and its color made a splash of rich pink light in the gray and white and black garden.

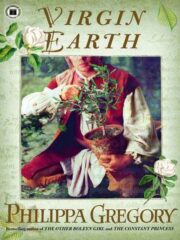

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.