The two old men got slowly to their feet.

“Love is not enough,” said the old man. “You need custom and kinship as well. Love her all you like. There is no shame in it. But choose your people and stay with them. That is the path of a brave.”

Without another word the old men went out, their bare feet passing within an inch of John’s face. He lay on the skins, the very symbol of a man brought low, and let them walk past him.

It grew dark. John lay still. He did not notice the thickening of the light and the spreading shadows on the wall. He heard the distant sound of singing and knew that dinner had been cooked and eaten and that Suckahanna’s people were at the dancing circle, singing down the moon, singing the fine weather in, singing the herds of deer toward them, singing the fish into the weirs and the seeds strong and tall out of the ground. John lay face down in the skins and neither wished nor wept. He knew his own emptiness.

A light came to the doorway, a twig of burning candlewood, bright as the best wax in London. Beneath it, half lit, half shadowed, was Suckahanna.

“You told them you did not want me?” she asked from the doorway.

“I failed a test,” John said. He sat up and rubbed a hand over his face. He felt immensely weary. “They said I should have to fight against my own people and I could not agree to do it.”

“Very well.” She turned to go.

“Suckahanna!” he cried and the desperation and passion in his voice would have made any woman pause but a woman of the Powhatan. She did not even hesitate. She did not drag her feet. She went out as lightly stepping as if she were about to join a dance. John leaped up from the floor and ran out after her. She must have heard him coming, she knew the rhythm of his stride from her girlhood, but she did not hesitate nor look around. She walked without breaking her pace down the little street to her own house, parted the deerskin at the door and slipped inside without even glancing back.

John skidded to a standstill and felt an urge to scream and hammer his fist through the wall of the light, beautifully made house. He took a sobbing breath and turned toward the fire at the dancing circle.

They were dancing for joy, it was not a religious ceremony. He could tell that at once since the werowance was seated on a low stool with only an ordinary cape thrown for warmth around his shoulders, and no sacred abalone shells around his neck. He was clapping his hands to the music of the drums and flutes, and smiling.

John went toward the light but knew that he was not suddenly revealed. They would all have seen him in the shadows, sensed him running after Suckahanna and then turning back to them. He skirted the beaten earth of the dancing floor and worked his way around to the werowance’s seat. The three old men glared at him with the bland amusement of cynical old age which always enjoys the diversion of youthful pain.

“Ah, the visitor,” said the werowance.

“I want to marry her,” John announced without preamble. “And my children will be Powhatan, and my heart will be with the Powhatan. And you may command me as a brave.”

The sharp, beaky face gleamed with pleasure. “You have changed your mind,” the werowance observed.

“I have learned the price,” John said. “I am not a changeable man. I did not know what Suckahanna would cost me. Now you have told me and I know. And I agree.”

One of the men smiled. “A merchant, a trader,” he said, and it was not a compliment.

“Your children to be Powhatan?” the other old man confirmed. “And you to be our brave?”

John nodded.

“Against your own people?”

“I trust it will never come to that.”

“If it ever does?”

John nodded again. “Yes.”

The werowance rose to his feet. At once the drumming stopped, the dancing halted. He put out his arm and John, uncertainly, went toward him. The thin arm came down lightly on John’s broad shoulders but he could feel the strength of the sinews in the hand as the werowance gripped him.

“The Englishman wants to be a brave of the Powhatan and marry Suckahanna,” the werowance announced in Powhatan. “We are all in agreement. Tomorrow he goes hunting with the braves. He marries her as soon as he has shown he can catch his own deer.” John scowled at the effort of understanding what was being said. Then the beaky face turned toward him and the werowance spoke in English.

“You have a day to prove yourself,” he said. “One day only. If you cannot mark, hunt and kill your deer in the day from dawn to sunset then you must go back to your people and their gunpowder. If you want a Powhatan woman then you have to be able to feed her with your hands.”

Suckahanna’s husband grinned at John from the center of the dancing circle. “Tomorrow then,” he said invitingly in Powhatan, not caring whether John understood or not. “We start at dawn.”

At dawn they were in the river, in the deep, solemn silence of the prayers for the rising of the sun. Around the braves, scattered on the water, were the smoking leaves of the wild tobacco plant, acrid and powerful in the morning air. The braves and the women stood waist-deep in the icy water in the half-darkness, washed themselves, prayed for purity, burned the tobacco and scattered the burning leaves. The embers, like fireflies, swirled away downriver, sparks against the grayness.

John waited on the bank, his head bowed in respect. He did not think he should join them until he was invited, and anyway, his own strict religious background meant that he shrank in fear for his immortal soul. The story of the Hare and the man and the woman in his bag was clearly nonsense. But was it any more nonsense than a story about a woman visited by the Holy Ghost, bearing God’s own child before kneeling oxen while angels sang above them?

When the people turned and came out of the water their faces were serene, as if they had seen something which would last them all the day, as if they had been touched by a tongue of fire. John stepped forward from the bushes and said in careful Powhatan, “I am ready,” to Suckahanna’s husband.

The man looked him up and down. John was dressed like a brave in a buckskin shirt and buckskin pinny. He had learned to walk without his boots and on his feet were Powhatan moccasins, though his feet would never be as hard as those of men who had run over stones and through rivers and climbed rocks barefoot since childhood. John was no longer starved thin; he was lean and hardened like a hound.

Suckahanna’s husband grinned at John. “Ready?” he asked in his own language.

“Ready,” John replied, recognizing the challenge.

But first every man had to check his weapons, and sons and girls were sent running for spare arrowheads and shafts, and new string for a bow. Then a woman ran after them with her husband’s strip of dried meat which she had forgotten to give him. It was a full hour after sunrise before the hunting party trotted out of the village. John suppressed a smug sense of satisfaction at what he regarded as inefficient delays; but kept his face grave as they jogged past the women, setting off for the fields. There were catcalls and hoots of encouragement at the men’s hard pace and at John, keeping up in the rear.

“For a white man, he can run,” a woman said fairly to Suckahanna, and Suckahanna turned her head to look after them as if to demonstrate that she had not been watching and had not noticed.

John did not permit himself a grin of satisfaction. The fat had been leached off him during his hungry time in the woods and his stay in the Indian village had been hard work. He was always running errands from field to village, or helping the women with the heavy work of clearing the land. The food they gave him had built only muscle, and he knew that though he might be thirty-five this year he had never been healthier. He imagined that Attone would think that he would drop from the line of braves panting and gasping within the first ten minutes, but he would be proved wrong.

Ten minutes went by and John was gasping for breath and fighting the desire to drop out from the line. It was not that they moved so fast, John could easily have sprinted past them, it was the very steadiness of their pace which was so exhausting. It was not a run and it was not a walk, it was a walk on the balls of their feet, a fast walk which never quite broke into a run. It was hard on the calf muscles, it was hard on the arch of the instep. It was sweating agony on the lungs and the face and the chest and the whole racking frame of the Englishman as he tried first to run and then to walk and found himself forever out of stride.

He would not give up. John thought that he might die on the trail behind the Powhatan braves, but he would not return to the village and say that he had not even sighted the deer he had promised to kill because he had been out of breath and too weary to walk to the woods.

For another ten minutes, and another unbearable ten after that, the file of braves danced along the path, following in each other’s footsteps so precisely that anybody tracking them would think he was following only one man. Behind them came John, taking two steps to their one, then one and a half, then a little burst of a run, then back to a walk.

Suddenly they halted. Attone’s fingers had spread slightly as he held his hand to his side. No other signal was needed. The fingers opened and closed twice: deer, a herd. Forefinger and little finger were raised: with a stag. Attone looked back down the line of the hunting party and slowly, one by one, all the half-shaven heads turned to look back at John. There was a polite smile on Attone’s face which was soon mirrored down the line. Here was the herd, here was a stag. It was John’s hunt. How did he propose they should go about killing one, or preferably three, deer?

John looked around. Sometimes a hunting party would set fires in the forest and drive a herd of deer into an ambush. Even more skill was required for an individual hunter to stalk an animal. Attone was famous among the People for his gift of mimicry. He could throw a deerskin over his shoulders and strap a pair of horns to his head and get so close to an animal that he could stand alongside it and all but slide a hand over its shoulders and cut its throat as it grazed. John knew he could not emulate that expertise. It would have to be a drive and then a kill.

They were near to an abandoned white settlement. Some time ago there had been a house by the river here, the deer were grazing on shoots of maize between the grass. There was a jumble of sawn timber where a house had once been and there was a landing stage where the tobacco ship would have moored. It had all gone to ruin years before. The landing stage had sunk on its wooden legs into the treacherous river mud and now made a slippery pier into the river. John looked at the lie of the land and thought, for no reason at all, of his father telling him of the causeway on the Ile de Rhé and how the French had chased the English soldiers over the island and to the wooden road across the mudflats and then picked them off as the tide swirled in.

He nodded, affecting confidence, as if he had a plan, as if he had anything in his head more than a vision of something his father had done, whereas what he needed now, and so desperately, was something he himself could do.

Attone smiled encouragingly, raised his eyebrows in a parody of interest and optimism.

He waited.

They all waited for John. It was his hunt. It was his herd of deer. They were his braves. How were they to dispose themselves?

Feeling foolish but persisting despite his sense of complete incompetence, John pointed one man to the rear of the herd, another to the other side. He made a cupping shape with his hands: they were to surround the deer and drive them forward. He pointed to the river, to the sunken pier. They were to drive the deer in that direction.

Their faces as blank as impudent schoolboys, the men nodded. Yes indeed, if that was what John wanted. They would surround the deer. No one warned John to check the direction of the wind, to think how the men would get into place in time, to disperse them in stages so that each would get to his place as the others were also ready. It was John’s hunt, he should fail in his own way, without the distraction of their help.

He had beginner’s luck. Just as the men started to move into their places the rain started, heavy thick drops which laid the scent and hid the noise of the men moving through the woodland surrounding the clearing. And they were skilled hunters and could not restrain their skill. They could not move noisily or carelessly when they were encircling a herd of deer even if they wanted to, their training was too deeply engrained. They stepped lightly on dry twigs, they moved softly through crackling shrubs, they slid past thorns which would have caught in their buckskin clouts with the sharp noise of paper tearing. They might not care whether or not they helped John in his task; but they could not deny their own skill.

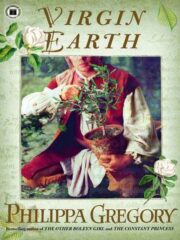

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.