He recognized Bertram at once despite the marks of hunger and fatigue on the man’s face. He was about to cry out in greeting but the English words were sluggish on his tongue; and then he realized that Bertram was pointing his musket at John’s belly.

“That’s mine,” Bertram snarled, showing his black and rotting teeth. “Mine. D’you hear? My food.”

John spread his hands in a quick deferential gesture, aware all the time of his razor-sharp reed arrows nestling in the quiver in the small of his back. He could have one on the string and loosed long before Bertram could reload and prime his musket. Was the man mad to threaten with an empty gun?

“Step back.” Bertram waved him aside. “Step back, or by God I’ll shoot you where you stand.”

John went back two, three steps, and watched with silent pity as Bertram hobbled over to the dead hare. There was precious little meat on it, and the rich guts and heart had been blasted out by the shot on to the snow. The silvery pelt, which would have been good to trade, had been destroyed too. Half the hare had been wasted by killing it with a gunshot, whereas Attone’s reed arrow should have gone straight to the heart and left nothing more than a farthing-size hole.

Bertram bent stiffly over the body, picked it up by the limp ears and stuffed it in his game bag. He bared his teeth at John. “Get away,” he said again. “I’ll kill you for staring at me with your evil dark eyes. This is my land, or at any rate, near enough mine. I won’t have you or your thieving people within ten miles of my fields. Get away with you or I’ll have the soldiers out from Jamestown to hunt you down. If your village is near here we’ll find it. We’ll find you and your cubs and burn the lot of you out.”

John stepped back, never taking his eyes from Bertram. The man’s face was a twisted ruin hammered from his old sunny, smiling confidence. John had no inclination to step forward now, to greet his old friend and shipmate by name, to make himself known. He did not want to know this man, this weak, cursing, stinking man. He did not want to claim kinship with him. The man threatened him like an enemy. If his gun had been reloaded John thought that it would have been his blood on the snow, and his belly blasted away like the hare’s. He bowed his head like a servile, frightened, enslaved Indian and backed away. In two, three paces, he was able to lean into the curve of a tree and know that a white man’s eyes would not be able to pick him out from the dapple of white snow and dark tree shadows and speckled bark.

Hobert glared into the shadowy forest which had swallowed up his enemy in seconds. “I know you’re there!” he shouted. “I could find you if I wanted.”

Attone came up beside John so silently that not even a twig cracked. “Who’s the smelly one?” he asked.

“My neighbor, the farmer, Bertram Hobert,” John said. The name sounded strange and awkward on his lips, he was so accustomed to the ripple of Powhatan speech.

“The winter has rotted his feet,” Attone remarked.

John saw that the brave was right. Bertram was painfully lame and instead of shoes or boots his feet were encased in thick wrappings tied with twine.

“That hurts,” Attone said. “He should wear bear grease and moccasins.”

“He does not know,” John said sadly. “He would not know that, and only your people could teach him.”

Attone gave him a quick smile at the unlikeliness of such a meeting and such a lesson. “He has our hare. Shall we kill him?”

John put his hand on Attone’s forearm as he reached for his arrow. “Spare him. He was my friend.”

Attone raised a dark eyebrow. “He was going to shoot you.”

“He didn’t know me. But he helped me build my house when I came to the plantation. We traveled across the sea together. He has a good wife. He was once my friend. I won’t see him shot for a hare.”

“I would shoot him for a mouse,” Attone remarked, but the arrow stayed in his quiver. “And now we will have to cross the river. There will be no game here for miles where he is stamping on his rotting feet.”

They caught no game though they stayed out for three days, traveling along the narrow trails which the People had used for centuries. Every now and then one of the trails would spread itself to double, even treble, the necessary width and then Attone would scowl and look out for a new house being built, a new headright created where this wide path would lead. Again and again they would see a new building standing proud, and facing the river and around it a desert of felled trees and roughly cleared land. Attone would look for a moment, his face expressionless, and then say to John: “We have to go on, there will be no game here.”

They struck away from the river on the second day, since the plantations chose the riverside so that the tobacco could be floated down to the quayside at Jamestown. Once they broke away from the riverbanks things were better for them. In the deeper forest they found traces of deer again and then on the third day, as they were bearing around in a wide circle for home, a great shadowy bush caught Tradescant’s eye and as he watched, it moved. Then he felt Attone’s hand on the small of his back and his breath as he said: “Elk.”

Something in the quiver of the brave’s voice set John’s heart racing too. The beast was massive, its antlers as broad as the outspread wings of a condor. Moving almost unconsciously, John fitted his arrow to his bow and felt the thinness of the shaft and the lightness of the sharpened reed arrowhead. Surely, this would be like shooting peas at a carthorse, he thought. Nothing could bring this monster down.

Attone was moving away from him. For a moment John thought they were to make the traditional pincer movement of deer-stalking, but then he saw that Attone had slung his bow over his shoulder and was climbing the lowest branches of one of the trees. When he was stretched along it with an arrow on the string he nodded to John with one of his darkest smiles.

John glanced back at the grazing elk. It was calm, unaware of their presence. John made a pointing upward gesture: should he climb too? Attone’s teeth flashed in a grin, white in the darkness. He shook his head. John should shoot at ground level.

John realized at once why this was apparently amusing. When the elk was struck it would look around for its enemy and it would charge the first thing it saw. That would be John. Attone, in the safety of the branch of the tree, would rain down arrows, but John on the ground below would serve as decoy: as bait. John scowled at Attone, who gave him the blandest of smiles and a shrug – it was the luck of the hunt.

John set his arrow on the string and waited. The elk sniffed the forest floor, searching for food. It turned full face to John and lifted its head for a moment, scenting the air. It was a perfect opportunity. Both arrows flew at the same second. John’s arrow, aimed for the heart, pierced the thick skin and layer of fat at the chest, while Attone’s plunged deep and unerringly into the beast’s eye. It bellowed in pain and plunged forward. A second arrow from Attone’s bow pierced its shoulder, severing the muscle of the foreleg so the animal dropped to one knee. John’s shaky second shot went wide and then he was running, dodging behind the trees as the beast came on, stumbled on, blood pouring from its head. Attone let fly one more arrow into the head again and then jumped from the tree, his knife in his hand. The flow of blood was weakening the animal, it was unable to charge. It fell to both knees, its head moving from one side to the other, the great sweep of the antlers still a danger. John peeped out from behind a tree and came running back, pulling his hunting knife with the sharp shell blade from its safe pouch. Either side of the wounded animal the two men watched for their chance. Attone, whispering the word of blessing on the dying creature, dived behind the moving antlers and plunged his knife between its high shoulders. The head slumped and John reached down and jabbed a hacking, sawing cut into the thick throat.

The two men jumped clear as the beast rolled on its side and died. Attone nodded. “Good and quick,” he said breathlessly. “Go, my brother, we thank you.”

John rubbed the sweat from his face with fingers that were wet with fresh blood. He dropped to sit on the snowy forest floor, his legs weak underneath him. “What if you had missed?” he asked.

Attone thought for a moment. “Missed?”

“When the beast was charging at me. What if you had missed your shot?”

Attone took a breath to answer and then John’s aggrieved face was too much for him; he could make no sensible reply. He whooped with laughter and dropped back on the cold snow. He laughed and laughed his great belly laugh of joy and John, trying to keep a straight face, trying to stay on his dignity, found it was too much for him and he started to laugh as well.

“Why ask? Why should it matter to you?” Attone demanded, wiping his eyes, and bubbling again. “You wouldn’t care. You’d be dead.”

John howled at the logic of this and the two men lay like lovers, side by side on their backs in the winter forest, and laughed until their empty bellies ached while the blue winter sky above them was darkened with the passing of the geese and the wood was louder with their honking than with laughter.

John was left to guard the carcass while Attone started the long run back to the village. It would be two days before he could bring the braves back to carry the meat into camp. John made himself as comfortable as he could for the wait, built a little bender tent of a pair of saplings and thatched it with thin winter fern, made himself a hearth at one side of it and let the tent fill with smoke for the warmth, and started the work of skinning and butchering the great beast. Attone had left his hunting knife with John, so that when John’s knife was blunted cutting the thick hide, fat and meat he would not have to waste time sharpening it. He worked from sunrise in the morning when he rose and said the Powhatan morning prayers at his morning wash in the icy water. At noon he gathered nuts and berries and ate with his dark gaze on the river, watching for shoals of fish. After his dinner he gathered firewood and set to work on the elk again. At night he cut a thin slice of elk meat to barbecue over the fire. John had lost completely the white man’s habit of gorging when food was available and starving when times were thin. He ate like one of the People, conscious all the time of the river that brought fish to him, and the winds that blew the birds to him and the woods that hid and offered the animals. It was not the way of a Powhatan to plunge into a trough of food like a hog into acorns. Food was not a free gift, it was part of a giving and taking, a balance; and a hunter must take with awareness.

In the two days and three nights while he waited John realized how much of a Powhatan he had become. The forest was no longer fearful to him. He thought how he had once seemed to be a little beetle crawling across a terrifying and infinite world. He now seemed no bigger, the Powhatan never thought of themselves as owners of the forest. He now felt as if this little beetle called John Tradescant, called Eagle, had found his place and his ordained path in this place, and that he need fear nothing since his place led him from the earth to birth and life and death and then to the earth again.

He knew there were wolves in the forest and soon they would get the scent of the elk, and so he built a rough fence of fallen branches around the carcass, and kept the fire lit. Now that he could eat well from the forest the immense labor of his English life seemed to him absurd. He could hardly remember how he had nearly starved in a wooden house set in a forest teeming with life. But then he remembered the hungry anger in Bertram’s twisted face and he knew that a man could live among plenty and never know that he was rich.

On the morning of the third day, as John methodically cut steaks of meat from the big animal’s body, he heard a tiny crackle of movement behind him and whirled around with his knife at the ready.

“Eagle, I give you greeting,” said Attone pleasantly.

Suckahanna was with him. John held out his arms to her and she came to him, her body as light as a girl in his grasp, her shoulders birdlike and bony.

“I brought your wife and my children, and some others to help cure the meat and to feast. They were hungry at home,” Attone said. “Build up the fire, they will come soon.”

John wiped Attone’s knife and returned it to him with a word of thanks and then he and Suckahanna piled John’s little brushwood fence onto his fire so that it flared up and crackled. As soon as it had burned down into hot embers Suckahanna brought large boulders from the river and heaped them with ashes to make them hot, then she laid dozens of small steaks of meat on the hot stones where they sizzled and spat. By the time the village had arrived – all those able to walk – there was meat cooked and ready for everyone.

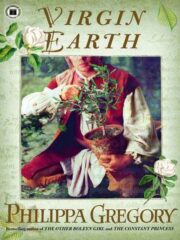

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.