I did not think I would ever be able to say it, but I am glad you are not here, husband. I miss you and so do the children but I do not know how a man could keep his wits and bear the sorrow of this kingdom, especially one like you who had served the king and the queen and seen them reap the consequences of their folly. There are rights, God-given rights, on both sides of the argument and all a woman can wonder is why the two sides cannot come together and resolve to live in peace. But they cannot, they will not, and God help them we all suffer while they hammer out the victory one on the other. Parliament is now in alliance with the Scots and they have sworn to defend each other against the king. But the Scots are a long way away and the king’s armies are very close, and everyone seems to think he has the advantage. Also, he has now recruited a Papist Irish army and we are all most afraid of their coming.

What seems more and more certain to me, when this is all over, is that we shall see the king in London again with his liberties barely trimmed, and those who have stood against him will have to pray God that he is more generous in victory than he was in peace time. Prince Rupert is said to be everywhere, and the other commander of the armies is the queen, so you can imagine how the king is advised between those two. Prince Maurice serves also and they have taken Bristol and Devizes this summer. Against the wealth of the king, the Parliament army makes a pitiful showing. The king has commanders who have fought all over Europe and know how it should be done, Prince Rupert has never lost a battle. Against them the Parliament puts plowboys and apprentice lads into the fields and the gentlemen mow them down like barley. We hear constantly from the Parliament of little battles which are fought at places of no name and mean nothing but are hailed as great victories.

However, the king has not yet approached London – and the City remains firmly against him. Your father-in-law, Mr. Hurte, has provided his own regiment to defend the City, he says – as all the merchants do – that the king cannot rule the City again. But since all the other great towns of the kingdom are falling to the king one by one then clearly, London cannot hold out alone – especially if the queen prevails on her French relations to join her husband. If a French army marches on Westminster the Parliament will have been defeated indeed, and I think it will be harder to be rid of the French Papists than it was to invite them.

Worse than the French Papists will be an Irish army. The great fear is that the king is planning all the time to flood the kingdom with Irishmen, but I cannot believe that such wickedness is in his mind. Not even he, surely, would sow such a whirlwind. If they could ever be prevailed upon to leave, what Englishman would ever trust the king’s word again?

The king holds Oxford of course, and his friends hold garrisons all the way up the Great North Road to Scotland. The queen holds York, and while she is in the field I have no hope of peace. The king’s army must march on London soon, and those of us who know not what to think (and that is most of us) can only hope that the city surrenders quickly.

The children are well, though running wild with neither school nor society to tame them. I will not let them go to the city which is full of the plague again, spread I am sure by the traveling soldiers who come and go from battle to village. I have had a one-way door set in our wall so that we can give food to passing paupers without any one of the servants having to open our front door. The bridge over the stream I have had made into a little drawbridge and we pull it up at night. I have completed the wall around the Ark and garden and sometimes I feel that I am a Mrs. Noah in very truth, peering over the edge of the Ark as the waters of the end of the world arise and swirl around me. It is on such nights that I feel very lonely and very afraid and I wish that I were with you.

Johnnie says that he will be a soldier and fight for the king. He has an etching of Prince Rupert on his black horse pinned to the head of his bed and makes most bloodthirsty prayers for his safety every night. He is a handsome, brave boy, as clever as any child in the kingdom. He is reading and writing in Latin and English and French, and I have set him to making the plant labels in English and Latin which he does without error. He misses you very much but he is proud of having a Virginia planter for a father, he thinks you are daily wrestling with bears and fighting Indians and prays for your safety every night.

Frances is well too. You would hardly recognize her, she has grown in these last few months from a girl to a young woman. She wears her hair pinned up now all the time and her skirts very long and elegant. I always knew she would be beautiful but she has surpassed my hopes for her. She has such a dainty prettiness about her. She is as fair as her mother, Mrs. Hurte tells me, but she has a lightness of spirit which is all her own. Sometimes she is too flighty, I am aware of it, and I try to reprove her, but she is such a merry dear that I cannot be too strict. She manages the garden in your absence and I think you will be proud of her when you return. She has a real way with plants and growing things. I often think it is such a shame that she cannot take your place in very truth and be another Tradescant gardener as she always wished to be.

It is her fate which is my greatest worry if the fighting should come near to London. I think that Johnnie and I could survive anything but a direct attack, but Frances is so pretty that she attracts notice wherever she goes. I dress her as plainly as I can and she always wears a cap on her head and a hood to cover her hair when she goes out, but there is something about her which turns men’s heads. I have seen her walk down the street and people simply look at her as if she were a flower or a statue, something rare and fine which they would like to take home with them. A wealthy man, whom I will not call a gentleman, visited the garden the other day and offered me ten pounds to give her to him. I had Joseph show him off the premises as quickly as you would wish, but it shows you the anxieties which I suffer over her. One of the kitchen maids – a fool – told Frances that the gentleman had taken a fancy to her and made an offer which was not of marriage, and before he had gone I am sorry to say that she climbed up on the garden wall, turned her back on him, and upended her skirts to show him her bum. I pulled her down and spanked her for indecency, and then thought she was crying most pitiably for shame, but when I had her right way up again I saw she could not speak for laughing. I sent her to her room in disgrace, and only when she was gone did I laugh too. She is a great mixture of minx and child and young lady, and I fancy the fine gentleman would have got more than he had bargained for.

If I think there is a chance of the fighting coming any closer I shall send her up the river to Oatlands, but with the country in this turmoil I do not know where she could be most safe. My choice, of course, is to keep her close by me.

My greatest adviser in these difficult times is your father’s friend and your uncle, Alexander Norman, who has the most immediate news of anyone. Since he sends out the ordnance from the Tower of London he always knows where the fiercest fighting has been and how much munition was used in every battle. He comes out to see us every week and brings us news and satisfies himself that we are well. He treats Frances as a complete young lady and Johnnie as the head of the household, and so they always welcome his arrival as their most favorite guest. Frances is never naughty when he is with us but very sober and careful, an excellent little housewife. When I told him of the man who had offered money for her he was more angry than I have ever seen him before and he would have challenged the man to a duel if I had given his name. I told him that the man had been punished enough but I did not tell him how.

And as for myself, husband, I will speak of myself though we were not married for love and have never been more than mere friends and for all I fear you do not think of me kindly since we parted on a disagreement. I am doing my duty according to my promise made to you at the altar and to your father on his deathbed to be a good wife to you, a mother to your children, and to guard the garden and the rarities. The beauty of the rarities, of the garden and of the children is my greatest joy, even in these difficult times when joy is hard to find. I miss you more bitterly than I had thought possible and I think often of a moment in the yard, a second in the hall, a letter which you once wrote to me which sounded almost loving, and I wonder perhaps if we had met each other in easier times whether we might have been lovers as well as husband and wife. I wish I had felt free to go with you on this venture, I wish you had held me so dear that you would not have gone without me, or felt as I do, tied to the house and the garden and the children. But you do not, and it is not to be, and I do not waste my time in mourning the failure of a dream that perhaps I am a fool to even think of.

So I am well, a little afraid sometimes, anxious all the time, working hard to keep your father’s inheritance together for you and for Johnnie, watching Frances, and praying for you, my dear, dear husband, and hoping that wherever you are, however far away you are from me and in such a strange land, you are safe and well and will one day come home to your constant wife, Hester.

John dropped to his knees on his mattress and then hunkered down. He read it all over again. The paper was fragile in parts where it had been wetted by sea water or rain, the ink had run on one or two words but the voice of Hester, her idiosyncratic, brave little voice sounded across the sea to her husband, telling him that she was keeping faith with him.

John was completely still. In the silence of the house he could hear the scratch of a squirrel’s claws on the roof above his head. He could hear a log shift in the hearth in the room below. Hester’s love and steadiness felt like a thread that could stretch all the way from England to Virginia and could guide him home, or it might wrap around his heart and tug at it. He thought of Frances growing up so mischievous and so beautiful, and of his funny little scholarly son who prayed for him every night and thought he was wrestling with bears, and then he thought of his wife, Hester, a true wife if ever a man had one, fortifying his house with her little drawbridge, managing the business and showing people the rarities even while she watched the progress of the war and planned their escape. She deserved better than a husband whose heart was elsewhere, who exploited her skill and her courage, and then left her.

John dropped his head in his hands. He thought that he must have been mad to leave his wife and his children and his home, madly selfish to leave them in the middle of a war, mad with folly to think that he could make a life for himself in a wilderness and mad with vanity to think that he could love and marry a young woman and make his life all over again, to his own mad pattern.

John stretched out on his mattress and heard a low groan of pain, his own sick heart.

He lay very still for some time. Down below Francis the Negro came in with a load of wood and dumped it by the hearth. “You in here, Mr. Tradescant?”

“Here,” John said. He dragged himself to the ladder and came down, his knees weak, the very grip of his fingers on the rungs seemed powerless.

Francis looked more closely at John and his face slightly softened. “Was it your letter? Bad news from your home?”

John shook his head and passed his hand over his face. “No. They’re managing without me. It just made me think I should be there.”

The Negro shrugged, as if the weight of exile was unbearably heavy on his own shoulders. “Sometimes a man cannot be where he should be.”

“Yes, but I chose to come here,” John said.

A slow smile lightened the man’s face, as if John’s folly was deliciously funny. “You chose this?”

John nodded. “I have a beautiful home in Lambeth and a wife who was ready to love me, and two healthy children growing every day, and I took it into my head that there was no life for me there, and that the woman I loved was here, and that I could start all over again, that I should start all over again.”

Francis kneeled at the hearth and stacked wood with steady deftness.

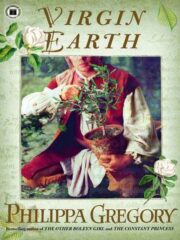

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.