A vessel was waiting to go, almost ready to cast off: the Makepeace, going to Virginia by the southern route and stopping at the Sugar Islands.

“I have to see the captain,” Hester said to one of the sailors. She was jostled by a family throwing their bundles on board and pushing their way toward the gangplank. “Or a trustworthy gentleman.”

“We’ve got a brace of vicars,” the man said rudely. “And half a dozen cavaliers. Take your pick.”

“I need a gentleman to assist me,” Hester said stoutly. “I shall see one of the clerical gentlemen.”

The sailor laughed, turned his head and shouted below. Hester smoothed her cape and wished that she had brought Johnnie with her, or even allowed Alexander Norman to come too. Eventually a white-haired man looked down from the ship’s side and said quietly, as if he would not raise his voice over the din of the ship, “I am the Reverend Walter de Carey. May I help you, madam?”

Hester stepped quickly up the swaying gangplank and held out her hand. “How do you do, I am Mrs. Tradescant, wife of John Tradescant of the Ark, Lambeth.”

He bowed over her hand. “I am honored,” he said.

“I am sorry to ask a favor of a stranger but my husband has been-” Hester paused for a moment. “Plant collecting in Virginia and finds himself without money. I have a note of credit for him but I need to find a trustworthy gentleman to take it to Virginia and give it to him.”

The man smiled wearily. “I am so little trusted that I have been expelled from my church and the blacksmith stands in my pulpit and tells my congregation what revelation he has gleaned that week from his forge fire,” he said. “I was twenty years in my vicarage and I baptized every single one of those young men and women who now tell me that I am in league with the Antichrist and a worshipper of the whore of Babylon. They would not call me a trustworthy man.”

Mutely, Hester held out the sealed and folded paper. “If you were twenty years in the vicarage and a good parish priest then you are the man for me,” she said. “These are hard times of change for us all. Will you help me try to bring my family back together? This is my husband’s passage money home.”

He hesitated for only a moment and then he took the paper. “Forgive me, I am too absorbed in my own sorrows. I will take the paper; but how will I find your husband?”

“He’ll find you,” Hester said with certainty. “He’ll be waiting for this. All you have to do is to tell people in Jamestown that you are looking for him and he will find you. Whereabouts are you going in Virginia?”

“I hope to settle there and found a school,” the vicar said. “The times are against men who believe in the king and God in this country. I trust that the new world will be a refuge for men of steady faith. Half this ship is filled with men like me, who cannot bear the new rule of Parliament and the wild heresies of madmen and self-taught preachers and the like in our own churches.”

“My husband left at the outbreak of the war,” Hester said. “He could not bear to watch the country being torn apart, and it was tearing him apart too.”

“He will come home to difficult times,” the vicar remarked. “The fighting may be nearly over, but the bitterness of these years will not be easily restored. And what is to become of the king in the hands of such a crew?”

There was a shout from the bridge and an answering shout from the shore.

“I must go,” Hester said hurriedly. “I do thank you for accepting the letter for John. He will do all he can to help you when he meets you, I know he will. He will be grateful.”

The vicar bowed. Hester turned for the gangplank and went down it as the lumpers on the dockside shouted to the sailors on the ship and finally cast off from shore.

“God speed,” Hester called to the ship. “Tell him I am waiting.”

The vicar put his hand to his ear, so Hester waved with a smile on her face and said more quietly, so he would be certain not to hear, “Tell him I love him.”

Autumn 1645, Virginia

John found that he had learned patience from the Powhatan, as well as the skill of living off the land. When he knew for certain that nothing he could do or say could save Opechancanough from death he went back to the farmer at the edge of the forest and agreed with him that he would work four days a week for his food and bed and a pittance of a wage, and three days of the week he would be free to go collecting in the near-virgin woods around the plantation.

Only a year before he would have been irritable, longing for the ship to come to release him from this service so that he could go home. But John found a sense of peace. He felt this was an interlude between his life with Suckahanna and the Powhatan, and the return – which must be a difficult experience – to Hester and the Ark at Lambeth.

In the days when he worked in the fields he was employed in harvesting the tobacco crop, taking the leaves to the drying sheds, baling them up and then loading them onto the ships which stopped at the little quay as their last port of call before setting off across the Atlantic.

In the days when he was free to roam he took his duckskin satchel, now properly cleaned, and went out into the woods with nothing more than a knife, a trowel, a bow across his shoulder and a couple of arrows in his quiver. It was a secret life he lived once he was out of sight of the planter’s house. As soon as he reached the shelter of the trees he stopped and shed his heavy clothes and kicked off his painful shoes. He wrapped them and hid them in a tree, just as Suckahanna the little girl used to do with her servant’s gown, and then he went barefoot and naked but for his buckskin through the forest and felt himself to be a free man once again.

Even after his years in the wilderness he had not lost his sense of awe at the strangeness and beauty of this country. He longed to bring it home entire, but he forced himself to choose the best of the shrubs and trees that he found on his long, loping surveys. He found a type of daisy that he thought had never been seen before, a big-flowered daisy with curious petals. He dug up half a dozen roots and packed them into damp soil, hoping they would survive until he had a ship for home. He took cuttings of the vine which Suckahanna had planted at his doorstep all that long time ago. He recognized it now. It was a favorite of hers: a sweet woodbine which some people called honeysuckle, but growing here with long scarlet flowers like fingers. He had a new convolvulus which he would name for himself, “Tradescantia.” He found a foxglove which was like the English variety but stronger-colored and bigger in shape. He potted up a Virginian yucca, a Virginian locust tree, a Virginian nettle tree. He found a Virginian mulberry which reminded him of the silkworms and the mulberry trees at Oatlands Palace. He found a wonderful pink spiderwort, the only flower his father had put his own name to, and kept the corms dry and safe, hoping they would grow in memory of his father. He dug up the dry roots of Virginian roses, certain that they would grow differently alongside their English cousins if he could only get them safe home to Lambeth.

Specimen after specimen he brought back to the little farmhouse and heeled in the growing plants into his nursery beds and laid the seeds in sand or rice to keep them dry. Plant after plant he brought in to add to the Lambeth collection. And as he added a new tree, the Virginian maple, or a new flower, the yellow willow herb, or a new herb, Virginian parsley, he realized that he would bring back to England an explosion of strangeness. If the country had been at peace and ready to attend to its gardens he would have been hailed as a worker of miracles, a greater plantsman and botanist even than his father.

He believed that he thought of nothing but his plants on these long expeditions when he was gone from dawn to dusk and sometimes from dawn till dawn, when he slept in the woods despite the cold winds which warned of the change of season. But somewhere in his heart and in his mind he was saying farewell: to Suckahanna the girl, whose innocence he had prized so highly, to Suckahanna the young woman he had loved, and to Suckahanna the proud, beautiful woman who had taken him into her heart and into her bed and in the end sent him away.

John said good-bye to her, and good-bye to the forest that she had loved and shared with him, and by the time the Makepeace sailed by the end of the pier and went upriver to dock at Jamestown, John had said his farewells and was ready to leave.

He had half a dozen barrels of seeds and roots packed in sand. He had two barrels of saplings planted in shallow earth and watered by hand every day. He left them on the end of the pier ready for collection and paddled the canoe upriver to Jamestown to see if this latest ship had brought him a message and the money from Hester.

He hardly expected it. It could be this ship or a later one. But it was part of John’s ritual of saying farewell to Suckahanna and making a new troth with Hester that he should be on the quayside to greet every ship, to show his trust that Hester would work as fast as she could to get the money to him. Their plan should not miscarry through his fault.

There was the usual crowd, shouting greetings and offering goods and rooms for hire. There was the usual anarchy of arrival: goods thrown on the quayside, children squealing with excitement, friends greeting each other, deals being struck. John stood up on a capstan and shouted over the heads of the crowd: “Anyone with a message for John Tradescant?”

No one replied at first so he shouted again and again like a costermonger bawling out his wares. Then a white-haired man, looking frail and sick, came down the gangplank with one eye on his sea chest of belongings and lifted his head and said:

“I!”

“Praise God,” John said and jumped down from his vantage point, and knew at the same time the plummet of disappointment that now there was nothing more to stay for, and he must leave Suckahanna’s land, just as he had left her.

He pushed through the crowd with a smile of greeting on his face. “I am John Tradescant.”

“I am the Reverend Walter de Carey. Your wife trusted me with a letter for you.”

“Was she well?”

The older man nodded. “She looked well. A woman of some courage, I should imagine.”

John thought of Hester’s stubborn determination. “Above rubies,” he said shortly. He opened the letter and saw at once that she had done as he asked. He had only to go to the Virginia Company offices and claim his twenty pounds, Hester had paid the money for him to a London goldsmith and the deed attested to it.

“I thank you,” he said. “Now, is there any service I can do for you? Do you have somewhere to stay? Can I help you with your bags?”

“If you could help me carry this sea chest,” the man said hesitantly. “I had thought there would be some porters or servants…”

“This is Virginia,” John warned him. “They’re all freeholders here.”

Winter 1645, England

In October Frances and Alexander Norman came upriver to Lambeth to stay for two nights. Hester urged them to stay longer but Alexander said he dared not leave his business for too long, the war must be coming to an end, every day he was sending out new consignments of gunpowder barrels and there were rumors that Basing House had fallen to Cromwell’s army at last.

It was not that it was such a strategic point, not like Bristol – the second city of the kingdom – which Prince Rupert had lost only the month before. But it was a place which had captured people’s imagination for its stubborn adherence to the king. When Johnnie knew that Rupert was dismissed from the king’s service, Basing House became his second choice. It was to Basing House where he planned to run and enlist. Even Hester, with memories of a court which were not all of playacting and folly but which also had moments of great beauty and glamour, longed to know that whatever else changed in the kingdom, Basing House still held for King Charles.

It was owned by the Marquess of Winchester, who had renamed it Loyalty House, and locked the gates when the country around him went Parliamentarian. That defiance seemed to Hester a more glorious way to spend the war than gardening at Lambeth and selling tulips to Parliamentarians. Inigo Jones, who had known Johnnie’s grandfather and worked with him for the Duke of Buckingham, was safe behind the strong defenses of his own design at Basing House, the artist Wenceslaus Hollar, a friend of the Tradescants, and dozens of others known to Hester had taken refuge there. There were rumors of twenty Jesuit priests in hiding and a giant of seven feet tall. The marchioness herself and her children were in the siege and she had refused free passage out of the besieged house but decided to stay with her lord. She had engraved every windowpane of the house with the troth “Aimez Lovauté” so that as long as the house stood and the panes were unbroken it would carry a record that one place at least was always unwaveringly for Charles.

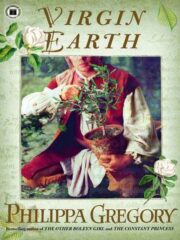

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.