“I can’t bear to chop it down,” John said. “It has grown to a good size even if it is not bearing much of a crop.”

“Can you move it?” Hester asked. Her gaze went beyond the tree, to the doorway of the ice house where the ivy and the honeysuckle were planted. No one could have spotted its outline unless they were looking for it. She liked the thought of the garden plants helping to hide the rarities. There was some unity in the Ark if they all worked together to save the precious things.

“My father had a way of moving even big trees,” John said thoughtfully. “But it takes time. We’ll have to be patient. It will be a couple of months at the earliest.”

“Let’s do it,” Hester said. “I am ashamed of the rarities room as it is, I want the treasures back inside.” She did not tell John that while the king was held by the Scots she had no fears for the safety of the treasures or of the family. Hester had great faith in Scottish efficiency, and in the dour Covenanters’ immunity to Stuart charm. If the Scots were holding the king, even if they took him far away to Edinburgh, then Hester felt safe.

Hester remembered the moving of the cherry tree as an event which coincided with the death of the hopes of the runaway king. Both processes happened in slow stages. John dug a trench around his father’s cherry tree and watered it every morning and night. The news from Newcastle was that the king would agree to nothing: neither the proposals from England nor those from his hosts the Scots.

With the help of Joseph and Johnnie pulling the trunk slowly first one way and then the other, John dug underneath the tree and gently shoveled earth away from all but the greatest roots. A Scottish cleric who had wrestled with the king’s conscience for two months went home to Edinburgh and died, they said, of a broken heart, blaming himself that the most stubborn man in England could not be brought to see where his own interests lay.

John watered the tree richly with his father’s mixture of stinging-nettle soup, dung, and water, three times a day. They heard that the queen herself wrote to the king and begged him to make an agreement with the Scots, so that he might be king of Scotland at least.

John pruned the tree, carefully cutting away the branches which would sap the tree’s strength. The Scots Covenanters, debating with their royal prisoner, privately declared among themselves that he was mad, he must have been mad to come to them without an army, without power, without allies, and then imagine that they would fight a war for him, on his terms, against their co-religionists for nothing more than his thanks.

Johnnie and Joseph, with John and Alexander on the other side, gently thrust poles from one side of the crater around the tree to the other until it was supported, and then John went down into the mud-filled ditch and freed the last of the roots. The longest, strongest root he pulled gently from the mud and then cursed when it broke and he fell back into the slurry with a bump.

“That’s killed it,” Joseph said gloomily, and John climbed out of the ditch soaked through and irritable. Then the four men gently lifted the tree out of the ground and carried it down to the bottom of the orchard where a new hole was dug and waiting. They put it in, lovingly spread out the roots, backfilled the earth, and gently pressed it down. John stood back and admired his work.

“It’s crooked,” Frances said behind him.

John turned wrathfully on her.

“Just joking,” she said.

With the doorway clear, Hester tied a duster over her head to keep off the cobwebs and spiders and set to pulling aside the ivy and the honeysuckle. The key still worked in the lock, the door opened with a creak on the dirty hinges. John peered inside. The little round chamber was lined with straw and piled high with chests and boxes of his father’s treasures. He caught Hester’s dirty hand and kissed it. “Thank you for keeping them safe,” he said.

Autumn 1646

Hester, Johnnie and Joseph were lifting tulip bulbs in the garden of the Ark. They worked with their fingers in the cold soil. Even the common bulbs were too valuable to risk spearing with a fork or slicing with a spade. On the ground beside Hester were the precious porcelain bowls of the most valuable tulips, their expensive bulbs already lifted and separated, the sieved earth tipped back into the beds.

Joseph and Johnnie filled the labeled sacks with the Flame tulip bulbs. Almost every one had spawned a second, some of them had two or three bulblets nestling beside the first. All three gardeners were smiling in pleasure. Whether the price for tulips ever recovered or stayed as low as it had been thrust by the collapse of the market, still there was something rich and exciting about the wealth which made itself in silence and secrecy under the soil.

There was a step on the wooden floor of the terrace and Hester looked up to see John Lambert. He was looking very fine, dressed as well as always, with a deep violet feather in his hat, and a waterfall of white lace at his throat and cuffs. Hester got to her feet and felt a pang of annoyance at her dirty hands and disheveled hair. She whipped off her hessian apron and walked toward him.

“Forgive me coming unannounced,” he said, his dark smile taking in her rising blush. “I am so honored to see you working among your plants.”

“I’m all dirty,” Hester said, stepping back from his proffered hand.

“And I smell of horse,” he said cheerfully. “I am on my way from my home in Yorkshire. I couldn’t resist calling in to see if my tulips were ready.”

“They are.” Hester gestured to the three bulging sacks at the corner of the terrace. “I was going to send them to your London home.”

“I thought you might. That’s why I have come. I am on my way to Oxford and I wanted the special tulips there. I shall plant them in pots and have them in my rooms.”

Hester nodded. “I am sorry you will not meet my husband,” she said. “He is in London today. He has gone into trade in a small way with a West India planter and he is sending some goods out.”

“I am sorry not to meet him,” John Lambert said pleasantly. “But I hardly dare to delay. I am to be governor of Oxford while my health mends.”

Hester risked a quick glance at him. “I had heard you were ill – I was sorry.”

He gave her his warm, intimate smile. “I am well enough, and the work I set myself to do is all but done. Pray God we will have peace again, Mrs. Tradescant, and in the meantime I can sit down in Oxford and make sure that the colleges get back into some kind of order, and their treasures are safe.”

“These are hard times to be a guardian of beautiful things.”

“Better times coming soon,” he whispered. “May I take my tulips now?”

“Of course. Shall you want them all at Oxford?”

“Send the Flame tulips to my London house, my wife can plant them for me there. But the rare tulips and the Violetten I must have beside me.”

“If you breed a true violet one then do let us know,” Hester said, gesturing to Joseph to take the sack of labeled rare tulips out to the wagon waiting in the street beyond the garden gate. “We would buy one back from you.”

“I shall present it to you,” John Lambert said grandly. “A mark of respect to another guardian of treasure.” He glanced down the garden and saw Johnnie. “And how’s the cavalry officer these days?”

“Very disheartened,” Hester said. “Would you let him make his bow to you?”

John Lambert cupped his hands around his mouth and shouted: “Ho! Tradescant!”

Johnnie looked up at the shout and came up from the tulip beds at a run, skidded to a halt, and dipped in a bow.

“Major!” he said.

“Good day.”

Johnnie beamed at him.

“You must have been disappointed in recent months, I am sorry for it,” John Lambert said gently.

“I can’t see what went wrong,” Johnnie said passionately.

John Lambert thought for a moment. “It was mostly how we used the infantry,” he said. “Cromwell has them trained in such a way that they change formation very fast, and they can hold their ground even against a charge. And once the king dismissed Rupert then the morale among his commanders was very low. That’s one of the keys, especially in a war inside a country. Everyone’s got to trust each other. That’s what Cromwell got right, when he got the Members of Parliament out of the army. We made the army a family which prays together and thinks together and fights together.”

Johnnie nodded, listening avidly. “It wasn’t Prince Rupert’s fault that he lost Bristol!” he exclaimed.

“Indeed it was not,” John Lambert agreed. “It was mostly the weather. It rained and their gunpowder was soaked. They were going to mine the city walls, rather than let us take a fortified town. They had the mines dug and the gunpowder in place – but then it was wet and didn’t fire. No commander could have done anything about that. But there was another thing-”

“What, sir?”

“It’s about belief,” Lambert said slowly. “There are very few like you, Johnnie, who have such certainty about the king. But there are very many, most of my army in fact, who truly believe that if they can win the war that we can make a better country here, better for everyone. They think they are doing God’s work and man’s work. They think that they will make a world of greater justice and fairness – we think that.”

“Are you a Leveler, sir?” Johnnie asked. Hester would have interrupted but Lambert was unruffled.

“I think we all are in a way,” he said. “Some of us would go further than others, but all the honest men I know think that we should be governed by our consent, and not by the king’s whim. We think we should have a parliament elected by everyone in the country and that it should sit all the time and return to the country for election every three years. We don’t think that the king and only the king should decide when and where it sits, and whether or not he will listen to it.”

“I’m still a royalist,” Johnnie said stubbornly.

Lambert laughed. “Perhaps we can find a way to persuade you royalists that it is for the good of us all – king to beggar – that we live in some order and harmony. And now I must go.”

“Good luck,” Hester called, her hand on Johnnie’s shoulder. “Come again.”

“I’ll come next spring and bring my Violetten!” he called, and with a swirl of his cape he was gone.

Spring 1647

Johnnie sat in his rowing boat on the little lake at the bottom of the garden, a news-sheet spread before him, his coat turned up around his ears against the sharp frost. He was reading one of the many royalist papers that spread a mixture of good cheer and open lies in an effort to keep the king’s cause alive, even while he squabbled with his Scots hosts at Newcastle. This edition assured the reader that the king in his wisdom was forging an agreement which would convert the Scots from their stubborn determination never to accept the English prayer book or the English system of bishops. As soon as the Scots had agreed they would then sweep down through England, return the king to his throne and all would be well again.

Johnnie looked up and saw his father coming through the orchard. John waved and walked to the bank where a little pier stretched into the water.

“You must be freezing,” John remarked.

“A bit,” Johnnie said. “This can’t be right. The Scots aren’t likely to surrender all they believe in when they have all but won the war. They aren’t likely to start fighting for the king against Parliament when they’ve been allies with Parliament for the last few years.”

“No,” John said briefly. “You bought the paper. What did you think it would tell you: the truth?”

“I just want to know!” Johnnie sat up abruptly and the boat rocked. “He has no chance, has he?”

John shook his head. “What your paper doesn’t tell you is that they’ve refused to take him to Edinburgh unless he too signs their covenant, against Laud’s prayer book and against the bishops. Of course he can’t sign. He’s just turned the kingdom upside down to try and make us do it his way. But the Scots are going back to Scotland, and they don’t know what to do with him. Nobody knows why he went to them in the first place. There was never any chance of an agreement. They’ll send him to Parliament.”

Johnnie went pale. “Betray him to his enemies?”

“He’s with his enemies already but he wouldn’t see it,” John said bluntly. “The Scots and Parliament have been allies since the war started. Of course they would work on him to try and make a peace. Of course if he won’t bend they have to hand him over.”

“What will he do?” Johnnie asked, anguished.

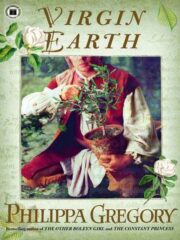

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.