He gave her a friendly nod and crossed the little bridge to the road before Hester could say another word. She watched him march up the road to the ferry at Lambeth before she closed the door and went to find John in the garden.

He was pruning the roses with a sharp knife, his hands a mass of scratches from his work.

“Why won’t you wear gloves?” Hester remarked irritably.

He grinned. “I always mean to, then I start work and I think I can do it without scratching myself, and then I can’t be troubled to stop and go and find them, and then I draw blood and think there’s no point in fetching them now.”

“You’ll never guess who came to the door.”

“All right. I never will.”

“A messenger from the king,” she said, watching for his reaction.

He stiffened, like an old hunter when it hears the hunting horn. “The king sent for me?”

She nodded. “To attend him at Windsor. The man was clear that you need not go unless you wish. The king has no power to order you to obey. But he brought the message.”

John stepped carefully through the rosebushes, disentangling his coat when it was caught by a thorn, his mind already at Windsor.

“What can he want of me?”

She shrugged. “Not some harebrained scheme of escape?”

He shook his head. “Surely not. But there’s nothing to interest him in the garden at this time of year.”

“Will you go?”

Already he was walking toward the house, his pruning knife slipped in his belt, his roses almost forgotten. “Of course I have to go,” he said.

They had no horse, there was not enough money to replace the mare who had carried Johnnie to Colchester and been slaughtered for meat during the siege. John walked to the ferry at Lambeth and took a boat upriver to Windsor.

The castle looked much the same: a guard of soldiers at the door, the usual bustle and work that surrounded the royal court. But it was all strangely diminished: quieter, with less excitement, as if even the kitchen maids no longer believed that they were cooking the meat of God’s own anointed representative on earth, but instead working in a kitchen for a mere mortal.

John paused before the crossed pikes of the men on guard.

“John Tradescant,” he said. “The king sent for me.”

The pikes were lifted. “He’s at his dinner,” one of the soldiers said.

John went through the gateway, through the inner court, and into the great hall.

There was an eerie sense of a life lived again. There was the royal canopy billowing a little in the drafts from the open windows. There was the king seated in state below it, the great chair before the great table, and the table crowded with dishes. There were the common people, crammed into the gallery, watching the king eat as they always did. There was the yeoman usher to declare the table ready for laying, the yeoman of ewry to spread the cloth, the yeoman of pantry to lay out the long knives, spoons, salt and trenchers, the yeoman of cellar standing behind the chair with the decanter of wine. It was all as it had been, and yet it was completely different.

There was no constant ripple of laughter and wit, there was no vying for the eye of the king. There was no plump, ringleted queen at his side, and none of the glorious portraits and tapestries which had always been hung in his sight.

And Charles himself was changed. His face was scarred with disappointment, deep bags beneath his dark eyes, lines on his forehead, his hair thinner and streaked with gray, his mustache and beard still perfectly combed, but paler with white hairs where it had been glossy brown.

He looked down the hall and saw John; but his habitual diffidence did not allow him to greet a friendly face. He merely nodded and with a tiny gesture indicated that John should wait.

John, who had dropped to his knee as he came into the hall, rose up and took a seat at a table.

“What you kneeling for?” a man asked critically.

John hesitated. “Habit, I suppose. Do you not kneel in his presence?”

“Why should I? He’s no more than a man, as I am.”

“Times are changing,” John observed.

“You eating?” another man said.

John looked around. These were not the elegant courtiers who used to dine in the hall. These were the soldiers of Cromwell’s army, unimpressed by the ritual. Hungry, honest, straightforward men at their dinner.

John drew a trencher toward him and took a spoonful of meat from the common bowl.

When the king had finished dining one yeoman came forward and offered him a bowl to wash his fingertips while another offered the fine linen cloth to dry his hands. Neither of them kneeled, John noticed, and wondered if the king would refuse their service.

He did not even complain. The king took the service as it would have been offered to a mere lord of the manor. He did not even remark that they were not on their knees. John saw the mystery of kingship shrink before his eyes.

John rose at his place, waiting for an order. The king crooked his finger and John approached the high table, paused and bowed.

King Charles rose from his seat, stepped down from the dais and snapped his fingers for a pageboy, who sprang to follow him.

“I d-dined on melons two nights ago,” he remarked to John as if no time at all had passed since John and the queen and the king had planned the planting of Oatlands together. “And I th-th-thought that we always said we should have a m-melon bed at Wimbledon. I saved you the seeds for p-planting.”

John bowed, his mind whirling. “Your Majesty?”

The pageboy stepped forward and handed John a little wooden box filled with seeds.

“W-will they grow at Wimbledon?” the king asked as he walked past John to his inner chamber.

“I should think so, Your Majesty,” John said. He waited for more.

“Good,” said the king. “Her M-Majesty will like that, when she s-sees it. When she comes h-h-home again.”

“And then he was gone,” John said to an astounded Hester and Johnnie, sitting at the fireside after a long, cold boat trip back to Lambeth.

“He summoned you all that way to give you melon seeds?” Hester demanded.

“I thought it might be some secret,” John confessed. “I searched the box, and I waited all day in case he should send a secret message for me, once he knew I was in the castle. I weeded the flower bed beneath the window of his privy apartments so that he would know I was there. But… nothing. It was truly just for the melon seeds.”

“He is to stand trial for treason, and he is thinking about planting melons?” Hester wondered.

John nodded. “That is the king indeed,” he said.

“Where will you plant them?” Johnnie asked.

John looked at the taut face of his son, at the shadows under his eyes and the continual frown of pain.

“Would you like to help me?” he offered gently. “We could make a proper melon bed at Wimbledon. My father taught me the way, and he was taught by Lord Wootton at Canterbury. We were there when I was a boy. Would you like me to teach you how to do it, Johnnie? When the spring comes and you’re strong again?”

“Yes,” Johnnie said. “I’d like to plant them for the king.” He paused for a moment. “Will he see them grow, d’you think?”

January 1649

John packed a bag. Hester, watching him from the doorway, knew that she was powerless to stop him.

“I have to be there,” he said. “I can’t sit at home while he is on trial for his life. I have to see him. I can’t stand not to know what is going on.”

“Alexander could send you a message every day, tell you what has taken place,” Hester suggested.

“I have to be there,” John repeated. “This was my father’s master, and my own. I was there at the start of this. I have to see the end.”

“Who knows when the trial will be?” she asked. “They should have started this month and yet the date is put back and put back. Perhaps they don’t mean to try him at all, but just to frighten him into agreeing.”

“I have to be there,” John insisted. “If there is to be no trial, then I have to see that there is no trial. I’ll wait until it happens – if it happens.”

She nodded, resigned. “Send word to us then,” she said. “Johnnie is sick with anxiety.”

John swung his cloak over his shoulder and picked up his bag. “He’s young, he’ll mend.”

“He still thinks they should have held out longer at Colchester, or fought their way out,” she said. “When I think what this war has done to Johnnie, I wish the king was charged with treason. He has broken hearts up and down this country. He has turned against his people.”

“Johnnie will recover,” John said. “You don’t break your heart at fifteen.”

“No,” she said. “But when he should have been at school or playing in the fields the country was at war and I had to keep him home. When you should have been home to teach and guide him you were away because you knew the king would keep you in his service, wherever that service might lead. Then, when he should have been apprenticed to you and making beautiful gardens or traveling and collecting plants, he was under siege in Colchester for a battle which could neither be won nor lost. Johnnie has never had a chance to be free of the king and the king’s wars.”

“Maybe we’ll all be free of him at the end of this,” John said grimly.

John could not find a room in an inn near Westminster for love or money. He could not find a bed. He could not find a share of a bed. They were renting out stables and hayracks as sleeping accommodation for the hundreds and thousands of people who were flocking to see the king on trial.

If there had been half the sympathy that the king so confidently expected, there would have been a riot, or at the least intimidation of the commissioners. But there was no sense of outrage among the men and women who were packing into the City like herrings in a barrel. There was a sense of being spectators at the most remarkable event, of being safely in ringside seats to watch a cataclysm. They were birds above an earthquake, they were fish in a flood. The worst thing that could happen to a kingdom was happening now; and they were able to watch it.

Once the crowd got a taste of history, there was no chance that they would resist it. They had come to see the most extraordinary event in an extraordinary decade, and they wanted to go home having seen it. A reversal in favor of the king that resulted in his agreement with Parliament and resting safe in his bed would have left the crowd, even the royalists among them, with a sense of having been cheated. They had come to see the king on trial. Most of them would even acknowledge that they had come to see the king beheaded. Anything less would have been a disappointment.

John walked downriver to the Tower and knocked on Frances’s door, admiring the Christmas rose she had planted at one side.

“One of mine?” he asked her as she opened the door.

She hugged him as she answered. “Of course. Did you not know you had been robbed?”

“I’ve not been much in the garden,” he said. It was a statement of his deep distress, which she read at once.

“The king?”

“I’ve come to see his trial.”

“You had much better not go,” she said frankly, drawing him into the little hall and then into the parlor where a small fire of coal was burning.

“I have to,” John said shortly.

“Will you stay here tonight?”

He nodded. “If I may. There are no beds to be had in the City and I don’t want to go home.”

“Alexander is going, but I didn’t want to see it. I remember when the king came to the Ark that day, and I saw him, and the queen. They were both so young then, and so rich. They were wrapped in silk and ermine.”

John smiled, thinking of the little girl who had sat on the wall until her fingertips were blue with cold. “You wanted him to appoint you as the next Tradescant gardener.”

She leaned forward and stirred the coals so they flamed up. “It’s unbelievable that everything should be so changed. I don’t expect to be a gardener; but it is impossible to think that there may be no king.”

“You could be a gardener now,” John offered. “In these strange days anything is possible, I suppose. There are women preaching, aren’t there? And there were women fighting. There were hundreds of women who had their husbands’ and their fathers’ business in their charge while the men were off to war, and many still working because the men won’t be coming home again.”

Frances nodded, her face grave. “I thank God that Alexander’s work was here, and that Johnnie was too young for all but the very end.”

“Amen to that,” John said softly.

“Is Johnnie taking it hard?”

“He’s bound to,” John said. “I wouldn’t let him come to see the end of it. But I had to see it for myself.”

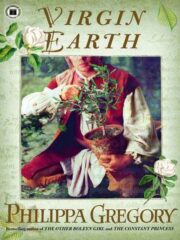

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.