“I might go and stay with Mother for a few days,” she said, looking out over the bright water.

“Why?” asked John. “Am I crowding you out?”

“I don’t want to be here when they do it,” she said.

For a moment he did not understand her. “Do what?”

“Behead him. They’ll do it here, won’t they? In the Tower? And put his head on Tower Bridge? I don’t want to see it. I know he’s been in the wrong, but I remember the day he came to the Ark and he was so handsome, and she was so pretty and dressed so richly. I don’t want to hear the drums roll and then stop for him.”

“I have to,” John said. “I feel I have to see the end of this.”

Frances nodded. “I think I’ll go and stay with Mother for a while when they start to build the scaffold.”

Saturday, 27 January 1649

Westminster Hall was more crowded than ever, John and Alexander were pressed against the railings and continually pushed against the broad back of a sentinel soldier. A little after midday the commissioners came into the hall; sixty-eight of them were present, Cromwell among them. When John Bradshaw came in wearing his hat John saw that he was robed in red, red as a cardinal, red as blood.

There was complete silence when King Charles came in, dressed in his rich black. He walked with purpose, and his face was bright. He no longer looked like an exhausted man pushed to his limit, he looked determined and filled with confidence. John, reading his master’s stance and face, whispered to Alexander: “He has a plan or something. He’s found a way out.”

Charles did not drop nonchalantly into his chair as he had done before. He seated himself and leaned forward earnestly and spoke at once, before Bradshaw could begin. “I shall desire a word to be heard a little,” he started.

Bradshaw at once refused. The proceedings were fixed, the king could not simply speak as he wished. Instead Bradshaw himself started to repeat the charge when there was a stir from the galleries where two masked women were sitting.

“Oliver Cromwell is a traitor!” one of the women shouted clearly.

“Take aim!” shouted the commander of the guard and at once the soldiers in the courtroom turned their muskets on the gallery. There was a scream and a rush away from the armed men, Alexander stumbled and grabbed at the railing. The women were hustled away and the guards went back to their positions. Alexander straightened his coat and brushed down his breeches. “This is unbearable,” he said to John. “I thought we were going to die in a riot.”

John nodded. “Look at Cromwell,” he said.

Cromwell was on his feet, his eyes raking the crowd, taking in the leaded windows through which an attack on the courtroom might be led. There was nothing. It had been nothing more than one woman crying out for her king.

Slowly, Cromwell resumed his seat, he glanced over to the king. Charles raised his eyebrows, slightly smiled. Cromwell’s face was grim.

Bradshaw, struggling to regain the attention of the court, ruled that the king’s refusal to speak was considered to be a confession of guilt, it would count as a guilty plea. But since the charge was so serious they would hear him speak in his defense as long as he did not challenge the authority of the court.

“They’re bending over backward to give him a fair chance,” Alexander whispered to John. “There’s no precedent for letting him speak in his defense when he won’t say whether or not he is guilty.”

The king leaned forward in his chair, his confidence increasing all the time. “For the peace of the kingdom and for the freedom of the people I shall say nothing about the jurisdiction of the court,” he said clearly. Again, there was no trace of his stammer. “If I cared more for my life than for the peace of the kingdom and the liberty of the subjects I should have made a particular debate and I might have delayed an ugly sentence. I have something to say which I desire may be heard before sentence is given. I desire to be heard in the Painted Chamber before the Lords and the Commons before any sentence is passed.”

“What?” John demanded.

“What can he be thinking of?” Alexander whispered. “A proposal of peace at last? Some kind of treaty?”

John nodded, his eyes on the king. “Look at him, he thinks he has the answer.”

Bradshaw was refusing, insisting on the court’s determination not to be delayed again when one commissioner – John Downes – started up. “Have we hearts of stone? Are we men?” he demanded.

Two judges either side of him tried to pull him down. “If I die for it I must speak against this!” he shouted.

Cromwell, seated before him, turned, his face black with fury. “Are you mad? Can you not sit still?”

“Sir, no! I cannot be quiet!” He raised his voice to reach everyone in the hall. “I am not satisfied!”

John Bradshaw surveyed the sixty-eight commissioners, saw half a dozen irresolute faces, a dozen men wishing they were elsewhere, a score of men who would have to be persuaded all over again, and announced that the court would withdraw to consider.

The king went out first, his step light, his head high, a slight triumphant smile on his face. The commissioners filed out after him, muttering to each other, clearly thrown off their course by this late offer. A draft of clean, cold air swept into the courtroom as the double doors were thrown open at the back and some of the crowd left.

John and Alexander kept their places. “I’m not leaving,” John said. “I swear he will escape the hangman. They’ll return with an agreement. He’s done it again.”

“I wouldn’t take a bet against it,” Alexander said. “He could easily do it. The commissioners are all of them uncertain, Cromwell looking ready to murder. The king has them on the run.”

“What d’you think they are doing now?” John asked.

“Cromwell wouldn’t purge them, would he?” Alexander speculated. “Rid himself of Downes and any that agree with him? He’s done it with Parliament, why not with the court?”

John was about to reply when the doors at the back of the hall were slammed shut, the usual signal that the court was about to reconvene, and then the king reentered, smiling slightly, like a man who is playing a role which is too absurdly easy for him to take seriously, and seated himself in his red armchair. Then the commissioners came in again. Downes was not with them.

“He’s not there,” Alexander said quickly. “That’s bad.”

John Bradshaw’s face was as grim as Cromwell’s. He announced that the court would not accept any more delays. There would be no calling of the Commons and the Lords. The court would proceed to sentence.

“But a little delay of a day or two further may bring peace to the kingdom,” Charles interrupted.

“No,” Bradshaw said. “We will not delay.”

“If you will hear me,” the king said sweetly. “I shall give some satisfaction to you all here, and to my people after that.”

“No,” Bradshaw said. “We will proceed to sentence.”

The king looked stunned, he had not thought they would resist the temptation of an agreement. He sat back in his chair for a moment and John could tell, from his absorbed expression and the gentle beating of his fingers on the arm of his chair, that he was thinking of another plan, another approach.

It was John Bradshaw’s great moment. He had a speech in his hand and he started to recite. He read slowly enough for all the writers from the journals to copy down what he was saying. He cited the traditional duty of Parliament and the duty of the king, and the claim that kings could be held accountable for their crimes. The crowd grew restless during the long legal citations but Bradshaw came to the point – that the king, by taking arms against his people, had destroyed the agreement between a king and his people. He was there to protect his people, never to attack.

“I would desire only one word before you give sentence,” the king interrupted.

“But sir, you have not owned us as a court, we need not have heard even one word from you.”

The king subsided into his chair as Bradshaw gestured to the clerk of the court.

“Charles Stuart as a tyrant, traitor, murderer and a public enemy shall be put to death by the severing of his head from his body.”

In silence the sixty-seven commissioners rose to their feet.

“Will you hear me a word, sir?” the king asked politely, as if nothing had taken place.

“You are not to be heard after sentence,” Bradshaw said and motioned to the guards to take him away.

The king leaned forward more urgently. He had not realized that they would not hear him after sentence had been passed. He knew so little of the laws of his own land that he had not realized a man sentenced is not allowed to speak. “I may speak after the sentence-” Charles argued, his voice a little higher in anxiety. “By your favor, sir, I may speak after the sentence.”

The guards came closer. John found he was shrinking back, a hand to his mouth like a frightened child.

Charles persisted. “By your favor, hold! The sentence, sir, I do-”

The guards closed in, forcing him to his feet. Charles shouted over their heads to the stunned crowd: “I am not suffered for to speak: expect what justice other people will have!”

They hustled him from the hall, there were confused shouts, some for, some against him. The commissioners filed out, John saw them go as if they were floating away, Bradshaw’s red gown and absurd hat a dreamlike imagining. “I never thought they would do it,” John said. “I never thought they would.”

Sunday, 28 January 1649

John would not attend church with Frances and her husband. He sat at the kitchen table, a glass of small ale before him, while the church bells rang and then fell silent, and then rang again.

Frances, entering in a rush to prepare the Sunday dinner, checked at the sight of her father, so uncharacteristically idle.

“Are you sick?”

He shook his head.

Alexander followed his wife into the kitchen. “They say he is praying with Bishop Juxon. He is allowed to see his children.”

“No clemency?” John asked.

“They are building the scaffold at Whitehall,” Alexander said shortly.

“Not here?” Frances asked quickly.

Alexander took her hand and kissed it. “No, my dear. Nowhere near us. They are closing off the street before the Banqueting House. They are fortifying it against a rescue attempt.”

“Who would rescue him?” John asked forlornly. “He has betrayed every one of his friends at one time or another.”

Tuesday, 30 January 1649

It was such a bitter, cold morning that John thought the ice on roof and gutter had crept into his own veins and was freezing his belly and bones as he waited in the street. The king was to be executed before noon but though the streets were lined three-deep with soldiers, and the two executioners waited in the lee of the black-draped scaffold, the note-takers and sketch artists gathered at the foot, there was no sign of the king.

The street, crammed with people packed in behind the cordon of soldiers, had a strange echo to it, as the sound of talk, prayers, and the shouts of ballad-sellers bawling out the titles of their new songs bounced off the walls of the windowless buildings and boomed in the cold air.

John, looking behind him at the tight-packed crowd and then forward to the stage, thought it seemed like an exercise in perspective, like Inigo Jones’s deceiving painted scenery for a masque, the penultimate scene of a masque which would be followed by the ascension, with Jehovah coming down from a great cloud and the handmaidens of Peace and Justice dancing together.

The two executioners climbed the steps to the platform and there was a gasp at their appearance. They were in costume, in false wigs and false beards and dark brown doublets and breeches.

“What are they wearing? Masquing clothes?” Alexander asked of the man on his left.

“Disguised to hide their identity,” the man said shortly. “It’ll be Brandon the hangman hidden under that beard, unless it’s Cromwell himself doing the job.”

John briefly closed his eyes and opened them again. The scene had not changed; it was still unbearable. The chief executioner positioned the block, laid down his ax and stepped back, his arms folded, waiting.

It was a long wait, the crowd grew restless.

“A reprieve?” Alexander suggested. “The plan he had for peace finally heard and accepted?”

“No,” someone said in the crowd nearby. “He has been stabbed to death by Cromwell himself.”

“I heard there was an escape,” someone else said. “He must have escaped. If he was dead they would show the body.”

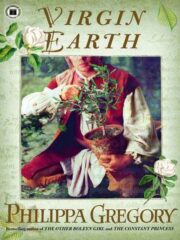

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.