The new king set up a new Privy Council and the great English cake of rewards and places was sliced up between royalists and their friends; but Charles took some care to see that experienced men and those from wealthy or noble families were recruited to office whatever they had done in the wars against his father. Those who had been party to the trial and execution of his father only lost their places of power and were fined, if they fled England.

“I think he’ll release John Lambert,” Frances said, bent over a newspaper spread out on the kitchen table. “It says here that the House of Lords seeks his death but the House of Commons wants him reprieved.”

“Will he be free?” Hester asked, looking up from shelling peas.

Frances shook her head. “It doesn’t say. But if I was Charles Stuart I don’t think I’d want Lord Lambert at the head of a regiment again.”

A month after the king was restored to the throne Elias Ashmole asked and got the place of a Windsor Herald. He came to visit the Ark wearing his new regalia, to suggest that John should publish a new edition of the catalogue.

“It should be dedicated to His Majesty,” Elias urged John as they sat on the terrace in the sunshine and looked over the garden which was in full summer bloom. “Think, if he were to come to visit! His father did, didn’t he?”

“Yes,” John said. “With the queen.”

“I hear she’s coming from France in the autumn,” Ashmole said enthusiastically. “We should have a new edition published by then. I’ll pay for it, if you wish. I have some money put by.”

“I can pay!” John said, nettled. “I’ll compose a dedication.”

“I have one already,” Elias said and produced from the deep pocket of his coat a folded manuscript. “Here.”

John spread the paper on the table.

To the sacred majesty of Charles the II

John Tradescant, His Majesties most obedient and most loyal subject in all humility offereth these collections.

Frances, looking over John’s shoulder, let out a little gurgle of laughter. “I don’t know if you’re his most obedient subject,” she remarked. “He surely has some servants that didn’t spend the wars as far away as they could get.”

John turned his laugh into a cough. “Frances, go about your business,” he said sternly and turned to Elias. “I apologize.”

“A flighty woman,” Ashmole said disapprovingly. “But if there is any question about your loyalty then you cannot affirm it too loudly, you know, John.”

John nodded.

“Fortunately you have the record of your son’s service,” Elias remarked. “You could always say he died at Worcester. Or died here of his wounds.”

Hester, coming to the terrace with a tray and three glasses of madeira wine, checked at that and exchanged a shocked look with her husband.

“We wouldn’t do that,” John said briefly. He got to his feet and took the tray from Hester’s hands. “Look at this that Mr. Ashmole has prepared for the printer for me. A new dedication for the front of the catalogue. Dedicated to His Majesty.”

She leaned over the table and read it carefully. To his surprise when she straightened up there were tears in her eyes.

“Hester?”

She turned a little away from the table so Elias Ashmole could not see her face. John followed her.

“What is it?” he asked quietly.

“I was just thinking how proud Johnnie would have been,” she said simply. “To see our name on the same page as the king’s. To have the collection dedicated to the king.”

John nodded. “Yes, he would have been,” he said. “His cause won the war in the end.” He turned to Elias Ashmole. “I thank you for your help, Elias. Let’s get it printed at once.”

Elias nodded. “I’ll deliver it to the printers on my way home,” he said cheerfully. “It’s no trouble. I’m glad you approve.”

Hester took her glass of wine and sat with the men. “Do we have guests for dinner tonight?” she asked. “Is Dr. Wharton and the rest coming for dinner?”

“Yes, and there’s news about that too!” Elias said gleefully. “We are to have royal patronage. The king is very interested in our thoughts and discoveries. We are to be called the Royal Society! Imagine that! We are to be fellows of the Royal Society! What d’you think?”

“That is an honor,” John said. “Though we’d never have gathered together if it hadn’t been for the republic. Under the bishops half what we discussed would have been called heresy.”

Elias flapped his hand dismissively. “Old days,” he said. “Old history. What matters now is that we have a king who loves to talk and speculate and who is prepared to advance men of science and learning.”

“Then why does he touch for the king’s evil?” Frances asked innocently, bringing a plate of biscuits, which she put at John’s elbow. “Is that not the superstition of ignorant people? Would he welcome an inquiry into such nonsense?”

Elias was briefly put out. “He does his duty, he does everything that is right and courteous and pleasing,” he said with emphasis. “Nothing more than good manners. Good manners, Mrs. Norman, are the very backbone of civilized society.”

“If you are a Royal Society I had best order a royal dinner,” Hester said tactfully. “Come and help me, Frances.”

Frances shot a grin at her father and followed her stepmother into the house.

It was a good summer for the Ark. The sense of safety and prosperity meant that more and more visitors came to the doors. The spirit of inquiry which the Royal Society represented spread throughout London, and men and women came to see the marvels of the Tradescant collection and then walk in the rich gardens and the orchards.

The horse chestnut avenue, which ran from the terrace before the rarities room to the end of the orchard, was now thirty-one years old, with broad trunks and wide, swaying branches. No one who saw the trees in flower could resist purchasing a sapling.

“There will be a chestnut tree in every park in the land,” John predicted. “My father always swore that they were the most beautiful trees he had ever grown.”

But the chestnuts had their rivals in the garden. John’s own tulip tree from Virginia flowered for the first time in the hot summer of 1660, and botanists and painters made special trips up the river to see the huge cupped flowers against the dark, glossy foliage. John had some new roses, Warner’s rose and a beautiful new specimen from France that they called the velvet rose for the deep, soft color of the petals. The fruit trees in the garden had shed their blossoms and were heavy laden with growing fruits. The early cherries were picked at dawn by Frances to save them from the songbirds, and sold at the garden gate by the lad. One part of the fruit garden was set aside for vines now; John had row upon row of well-pruned bushes, grown low on wires, just as his father had seen them grown in France, with fourteen varieties of grape, including the fox grape from Virginia and the Virginian wild vine.

In the melon beds John grew half a dozen varieties of melon. He always kept one fruit to the side, he called it the royal melon, descendant of the seeds Johnnie had planted at Wimbledon House. When it fruited in midsummer John sent a great sweet-smelling globe to the king, who was hunting at Richmond, with compliments of John Tradescant. He wondered if this was the second melon that Charles Stuart had received, and if he would ever understand the devotion that had been poured into growing the first fruit.

Autumn 1660

Castle Cornet, Guernsey.

Dear Mr. Tradescant,

Please would you send me, as soon as you lift them, six Iris Daley tulip, six Tricolor Crownes tulip and two or three tulip which you think I might like that are new to your collection.

If the new tenants of the house at Wimbledon have no objection, I should like you to collect from my garden any specimens which you would like to have as your own. I think the acacia tree was promised to you – all that long time ago. I particularly would like to see my own Violetten tulip again, I had one in particular which I thought might be so dark a purple as to be almost black.

If you can be admitted to the garden I would be very pleased to have some of my lily bulbs returned to me, especially those from my orange garden. I have high hopes of breeding a new variety of lily here and I will send you some bulbs in the spring. I shall call it the Lambert lily and my claim to fame shall not be for the battle for freedom but for one sweet-smelling, exquisitely shaped blossom.

Lady Lambert has joined me here with our children and the castle has become less like a prison and more like a home. All I am in need of, is tulips!

With best wishes to Mrs. Tradescant and Mrs. Norman -

John Lambert

John passed the letter to Hester without comment and she read it in silence.

“We’ll get him his Violetten back,” she said determinedly. “If I have to go over the Wimbledon garden wall at midnight.”

Winter 1660

Elias Ashmole came to visit the Ark in midwinter, wearing a new fur-lined cape and very conscious of his new status. He came by carriage with some friends and brought a case of Canary wine to share with John. Hester lit the candles in the rarities room, and ordered dinner for them all, served it and ate her own dinner in the quieter company of Cook in the kitchen.

John put his head around the kitchen door. “We’re taking a stroll down to Lambeth,” he said. “For a glass of ale.”

Hester nodded. “I shall be in bed by the time you return,” she said. “If Mr. Ashmole wishes to stay the bed is made up in his usual room, and there are truckle beds for his friends.”

John came into the kitchen and gave her a kiss on the forehead. “I shall be late home,” he announced with satisfaction. “And no doubt drunk.”

“No doubt,” Hester said with a smile. “Good night, husband.”

They came home earlier than she expected. She was putting out the candles in the rarities room and raking out the fire when she heard the front door open and John stumble into the hall with Ashmole and his companions.

“Ah, Hester,” John said happily. “I am glad you are still awake. Elias and I have been doing some business and I need you to witness it for me.”

“Can it not wait until the morning?” Hester asked.

“Oh, sign it now and then we can put it away and have a glass of port,” John said. He spread the paper before her on the painter’s table in the window of the rarities room. “Sign here.”

Hester hesitated. “What is it?”

“It’s a piece of business and we need a witness,” Elias said smoothly. “But if you are uneasy, Mrs. Tradescant, we can leave it until the morning. If you want to read every paragraph and every sentence, we can leave it. We can find someone else to serve us if you are unwilling.”

“No, no,” Hester said politely. “Of course I can sign it now.” She took the pen and signed the paper. “And now I shall go to bed,” she said. “I give you good night, gentlemen.”

John nodded, he was opening a case of coins. “Here you are,” he said to Ashmole. “In good faith.”

Hester saw the antique milled shilling piece passed to Elias.

“Are you giving away one of our coins?” she queried in surprise.

Ashmole bowed and pocketed the coin. “I’m very grateful,” he said. He seemed far more sober than John. “I shall preserve it very carefully as a precious token and a pledge.”

Hester hesitated, as if she would ask him what pledge John had made to him; but one of the men opened the door for her and bowed low. Hester curtsied and went out and up the stairs to bed.

She was wakened by the bang of her bedroom door as John stumbled into the room and then by the shake of the bed as he dropped heavily onto it. She opened her eyes and saw that he had fallen asleep at once, on his back, still wearing his clothes. Hester thought for a moment that she could get up and undress him and get him comfortable in bed. But then she smiled and turned over. John’s drinking bouts were rare but she saw no reason why he should not wake up in the morning in some slight discomfort.

When he woke in the darkness he thought for a moment he had been dreaming his worst dream: of failure and his own inability to inherit his father’s work and continue his father’s name. He slipped out of the narrow bed without waking Hester, who turned and stretched her hand out over his pillow.

He slipped on his shoes and went downstairs. The parlor which had seemed so bright and jolly only hours ago was now dark and unwelcoming, it smelled of stale ale and tobacco smoke, and the fire was burned down to dark embers. He blew on the coals, was rewarded by a red glow, and then threw on a handful of kindling. The dry wood caught and the shadows leaped high in the room.

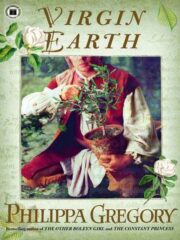

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.