It was midafternoon, and the border was only ten miles up the road. Clearly, her captors intended to carry Heather into Scotland that day.

Straightening from the wall, Breckenridge watched the coach for a moment more, then strode off to retrieve his trap from a nearby stable.

Heather felt a moment of simple panic as the coach rolled slowly across the bridge spanning the river Sark and rumbled into Scotland.

She told herself that Breckenridge would be close behind, that she wasn’t alone. That when the time came, he would help her escape. That helped.

Some miles back, the coach had passed a major road that led to Edinburgh via Hawick and Selkirk; they were, it seemed, definitely heading for Glasgow.

For the next few miles, the way was familiar to her. The village of Gretna lay just beyond the border, cottages spread haphazardly to the left of the highway. A minute later, also to the left, they passed the turn into the road she was accustomed to taking to Dumfries and ultimately to the Vale.

Sitting back, resting her head against the squabs, she reflected that she was now, for her, traveling into uncharted territory. She wondered how much further they would go that day. She’d asked multiple times, but all Fletcher or Martha would say was that she “would learn soon enough.”

She inwardly humphed and settled back, hugging the cloak Martha had provided closer; although it was spring, Scotland was distinctly cooler than southern England.

The coach slowed.

Glancing out of the window, she saw the cottages of the hamlet just north of Gretna. Gretna Green was notorious for the runaway marriages performed over the anvil of the blacksmith’s forge.

The coach slowed almost to a stop, then turned ponderously left.

Martha, looking out of the other window, said, “Is that it, then? The famous smithy?”

Fletcher flicked a glance that way. “Yes — that’s it.” He looked back and met Heather’s eyes. “We’re stopping at a little inn just down this lane.”

It was just one of their usual halts. Heather told herself that the proximity to the famous anvil was incidental. While they’d passed a number of inns in Gretna, the small country inn before which the coach pulled up was definitely more Fletcher’s style.

The Nutberry Moss Inn was old. Its two storeys looked worn, but also still solid. With walls of whitewashed stone, black window frames and doors, and immense black beams supporting the dark gray slate roof, it seemed sunk and anchored into the earth, as if it had literally put down roots.

Fletcher descended first, then handed Heather down. She paused on the coach step to glance around. There were few trees to impede her view. She didn’t see Breckenridge, but she did manage to get her bearings. The lane in which the inn stood continued further west, merging with the larger road to Dumfries a little way along.

Stepping down to the rough gravel of the forecourt, she scanned the front of the inn; it exuded an air of homely comfort. Then Martha joined her; with Cobbins bringing up the rear, they followed Fletcher into the inn.

Inside, it was a great deal warmer. Heather held out her hands to the small blaze in the fireplace built into one wall of the hall, and glanced around curiously. A set of narrow stairs led upward, dividing the front hall into two. The landlord had just come out of a swinging door at the rear of the hall to the left of the staircase; that door presumably led to the kitchens. Wiping his hands on a cloth, he welcomed Fletcher. On being informed they needed rooms, the landlord crossed to a long counter set against the wall to the right of the stairs.

Turning back to the fire, Heather was reviewing potential questions — reviewing what else she might learn from her captors — when she heard Fletcher inform the landlord, “Don’t know how many days we’ll be here. Two at least, but most likely more. We’ll be here until Sir Humphrey Wallace’s agent — a Mr. McKinsey — arrives to escort the young lady on.”

Swinging around, Heather stared at Fletcher — at his back. He remained engaged with the landlord, haggling over rooms.

Snapping back around, she pinned Martha with a demanding glare. “This is where you’re to hand me over? We’re waiting for this laird of yours here?”

Martha shrugged. “So Fletcher says.” Her hatchet face was entirely uncommunicative.

“But he’s not here yet?”

“No.” Martha resettled her shawl. “Seems it’ll take him a few days to reach here, wherever he’s coming from.”

Fletcher was still engaged with the innkeeper. Heather turned to Cobbins, as always standing near. “When did you send him word that you’d seized me and were bringing me north?”

As she’d hoped, Cobbins answered, “Put a message on the night mail at Knebworth.”

Heather calculated; she was losing track of the days, but. . if McKinsey had been in Edinburgh or Glasgow, he should be here, if not by now then certainly by tomorrow.

Before she could follow that idea further, Fletcher strolled up.

“Two rooms as usual, both in the east wing, but not next to each other.” He glanced at the two lads carrying in their bags. “Cobbins and I will take the room nearer the stairs.”

Heather straightened, lifted her chin. Narrowed her eyes on Fletcher’s face. “Why are we stopping here?”

Unconvincingly mild, Fletcher returned, “This was where McKinsey told us to bring you.”

“Why of all the towns in Scotland did he chose Gretna Green?”

Fletcher opened his eyes wide. “I don’t know.” He exchanged a glance with Martha, then looked back at Heather. “We might guess, but”—he shrugged—“we really don’t know. This is where he said, so this is where we’ve brought you. Far as we know, that’s all there is to it.”

And they didn’t believe that for a moment.

Heather absolutely definitely did not like the implications. She knew that, theoretically, a woman had to be willing to be married, over an anvil or any other way, in Scotland or anywhere else in the British Isles.

What she didn’t know was, in a place like Gretna Green, just how agreeable a woman had to be. Did she have to make any statement of agreement? Or could she be drugged or coerced in some way to ensure the deed was done?

One thing she did know was that marriages conducted over the anvil at Gretna Green were legal and binding. Her parents had been married there.

She made no demur when Martha shooed her up the stairs and ushered her to their room. Inside, she’d grown strangely detached. To her mind, the way forward had just become crystal clear. It was obviously time to leave her kidnappers, to cut and run with what she’d already learned. When Breckenridge arrived, she’d tell him she was ready to escape. .

Except Fletcher had said they’d be here for at least two more days.

Entering the room ahead of Martha, barely registering the pair of narrow beds and the single small window, Heather considered, but she didn’t think Fletcher had been lying. He wasn’t honest, but in general he focused on his route forward; she didn’t think he was likely to have invented the tale of having to wait for days.

Why would he? He didn’t know Breckenridge was close, her ready route out of their clutches. There was, from their point of view, no reason to lie to her about how long they would remain there, waiting on McKinsey’s arrival.

Sinking onto the bed further from the door, she stared at the wall and wondered if there was any way she could exploit the situation for her own ends. Whether with what she now knew, she could pressure Fletcher, Martha, and Cobbins for yet more about McKinsey. And when she ultimately decided to escape, whether that escape might be timed so that she and Breckenridge could remain close enough to watch and see McKinsey arrive.

If she and Breckenridge could get a good look at the man, they’d have a much better chance of identifying him, and subsequently nullifying any threat he might pose, now or later, to her sisters, her cousins, and herself.

Drawing in a deep breath, she put aside such speculations until she could discuss them with Breckenridge, then rose and crossed the room to open negotiations over what clothes her “maid” would allow her to retrieve from the large satchel Martha continued to guard like a terrier.

Breckenridge was in the tap, deep in his guise of a solicitor’s clerk, elbow to elbow with three locals, each consuming a serving of the inn’s dinner stew, when Heather and her captors walked into the room.

The inn was, fortuitously, too small to boast a separate dining room. Along with the other men, all older and distinctly more grizzled than he, he could look up, apparently distracted from his meal by the sight of a young lady of quality — no matter how Heather dressed, her carriage, her composure, screamed her antecedents — gliding into the room.

Briefly — fleetingly — he met her eyes. Hers had widened only slightly when she’d seen him; otherwise nothing showed in her expression as her gaze moved on, scanning the occupants of the tap, then passing on to the serving girl bustling up to steer her and the other three to a table at the front of the room.

Of all the men present, he was probably the only one who correctly read the upward tilt of her chin. She was putting on a good face, which meant something was troubling her.

Looking down at his plate, he inwardly frowned. She hadn’t previously seemed all that concerned with her captivity. Not that she hadn’t recognized it for what it was, but she’d seemed to view it as a cross to be borne until she could learn what lay behind it. Now. . something had changed.

Instinct prodded, more insistently this time. He hadn’t been thrilled by Fletcher’s choice of inn, not with that far-too-well-known smithy within easy walking distance, but given they’d assumed her captors were taking her to Glasgow, he’d viewed the Nutberry Moss Inn as simply a convenient halt.

Given Heather’s sudden concern, perhaps that wasn’t so.

Toying with the lumps of mutton swimming in the gravy filling his plate, he turned his mind to considering where, exactly, to meet her that night.

Across the small room, Heather sat on a bench with her back to the wall, wedged into the corner by Martha’s stout form. The only useful aspect of her position was that she could see Breckenridge where he sat with three locals at a table near the bar.

Even as she idly, apparently absentmindedly, stared in that direction, he made some comment and the other three laughed. His hair had been roughed up, so it no longer sat as it should, making him look more loutish, especially with his beard shading his cheeks and jaw. A napkin tucked into his collar, he had both elbows on the table, leaning on them as with a fork he scooped up stew — and spoke while he chewed. She’d never met his late mother, but could they see him, his sisters would be appalled.

Still, his disguise definitely worked. Although he wasn’t a local, and still clearly stood out as someone different, he nevertheless fitted into the Nutberry Moss’s picture. He appeared to belong.

The relief still coursing through her — that had flooded her the instant her eyes had alighted on his dark head — was intense; she must have been more worried than she’d let herself admit.

But now he was there, close, she could set aside said worry and concentrate on extracting every last piece of information she could before McKinsey’s pending arrival forced her to escape.

The serving girl arrived with their meals. Heather said nothing but applied herself to consuming the thinly sliced roast lamb, parsnip, and cabbage, while inwardly she compiled a list of all the little telltale snippets Fletcher, Cobbins, and Martha had let fall.

When Breckenridge and she met later, she would need to put forward all she’d learned in support of her contention that, with McKinsey still days away, they need be in no rush to slip away from the Nutberry Moss Inn. They could stay a few days more and see what more she might learn.

Although Fletcher kept looking at her assessingly — she suspected he was waiting for her to have hysterics over the implications of the nearness of the blacksmith’s forge — she kept her head down and clung to her passivity. It wasn’t at all natural, but her captors didn’t know that.

Once she finished mentally cataloguing all she’d learned, she turned her mind to what other questions she might conceivably ask — and her arguments for remaining to ask them.

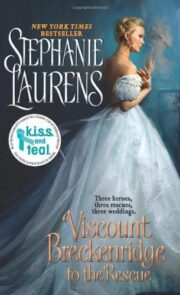

"Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue" друзьям в соцсетях.