Both he and Richard had grown to manhood in the midst of the ton, with all the wealth and privileges pertaining to those who belonged to the upper circles of the nobility. Yet he suspected that Richard, just like him, had always carried a question buried in the deepest recesses of his brain. A question that had to do with rightful place.

In Richard’s case, he’d had to find one, and he’d patently succeeded here in the Vale. It couldn’t have been easy; even though he’d spent less than a day on the estate, Breckenridge had sensed that it was Catriona who stood at the heart of the place, yet Richard had carved his own place, and had clearly earned it, by her side.

For himself. . Breckenridge’s question was slightly different. He had a place waiting for him — his father’s shoes. When his father died, he would become the Earl of Brunswick. Even though he already performed many of the duties, did much of the day-to-day work managing the estate, he still wondered if he would measure up when the time came.

For some reason, he knew that if he had Heather by his side, he would.

That if she were there, blithely expecting him to be all he could be, then he would be everything he needed to be, and, possibly, more.

Cantering beside Richard, Breckenridge turned into the Vale drive and rode steadily toward the manor; in the peace and the quiet, broken only by the tattoo of their horses’ hooves, he tried to analyze why he was so convinced he needed her, and only her, to succeed in his future life. . in the end, decided he had no clue.

But perhaps Richard was right.

Breckenridge had more at stake than Heather knew, than he could ever let her know, but perhaps making some concessions, revealing enough to engage her curiosity and, ultimately, her interest, would serve.

That, and taking a more aggressive, more commanding line in the liaison she apparently imagined he was going to allow to end.

Breckenridge next met Heather at the luncheon table. The seat beside her was empty; he claimed it, but Richard and Catriona’s older children — their first set of twins, Lucilla and Marcus — had joined the company about the high table and had selected the chairs opposite.

He quickly realized that the eight-year-old twins were determined to do what they saw as their social duty and keep the conversational ball rolling.

The topics they chose ranged from gentlemen’s hair styles — comparing Richard’s with his — to comments about the source of the lamb roast, identified by name, and Algaria’s dandelion wine, to speculation over whether they would have cause to visit London soon.

The pair cheerily discussed the latter at length, all with wide-eyed, innocent curiosity, which fooled him and Heather not at all.

He and she exchanged a glance, then both set themselves to divert attention to any other topic but the one that, transparently, was uppermost in every mind.

A brief glance over the hall confirmed that virtually everyone was living in eager expectation of hearing an engagement announced at any moment. Although the observation only fueled his frustration, the underlying irritation over not yet having secured her agreement to a wedding, in the circumstances, he kept his lips shut.

He did consider using nonverbal means to pursue his objective, but aside from them being too closely watched, he couldn’t, he realized, predict how Heather would react. With any other lady with whom he was engaged in a liaison, he wouldn’t have hesitated, but not with her, not least because his goal wasn’t simply to continue said liaison.

He’d never before wooed a woman. For one of his expertise, the realization that wooing wasn’t as easy as seducing was unsettling.

When the platters were empty and all were satisfyingly replete — and Algaria summoned the terrible twins to their afternoon lessons and shooed them before her from the hall — he reached out and, under the table, tugged Heather’s sleeve. Leaned nearer as she turned to him, captured her gaze and murmured, “We need to talk.”

She studied his eyes for a moment, then nodded. “All right.”

He eased back, considered. “Do you know somewhere we can talk without being interrupted or overheard — and preferably not seen?”

She grimaced. “Not being visible from the house isn’t easy, but if we go into the herb garden we’ll be far enough away. No one will be able to eavesdrop or easily approach, or to see our faces.”

He nodded, rose, and drew back her chair.

She led the way out of the emptying hall; ignoring the questioning glance Richard sent him, as well as Catriona’s serene regard, he strolled in her wake.

The herb garden was, perhaps predictably, large; it filled the wide swath of downward-sloping land that separated the manor’s walls from the banks of the small river. In the irregularly shaped beds, some specimens had only recently shaken free of winter’s hold and were tentatively unfurling green buds, while other plants were bursting forth with new foliage in bountiful profusion. At the bottom of the slope the river rushed along in full spate, gurgling over rocks, splashing against boulders embedded in the banks. The sound was happy, cheery, strangely soothing.

Hands in his pockets, he followed at Heather’s heels further, lower, into the thickly, richly, informally planted garden. Birdsong became drowned by the drone of bees flitting through the lavenders and the many and various other blooms he couldn’t name. The sun was high, its beaming warmth washing over the plants; the tapestry of scents that rose to wreathe around them was enough to make him giddy.

Heather led him toward the river, to a small indentation in the lower side of one bed, a curve carved into the rising bank and walled with stone. Within the curve, more blocks had been laid to create a bench. Walking to one end, with a swish of her skirts, she sat. He halted. When, looking up, she arched a brow at him, he inwardly shrugged and sat alongside her.

The sun shone, a gentle benediction, upon them; the warmed rock surrounding them cocooned them, the fine mist thrown up by the rushing river an occasional refreshing caress.

“Good choice.” Leaning back, he rested his shoulders against the wall’s upper edge and fixed his gaze on her face. Her profile was all he could see. “We need to settle this — and no, don’t tell me it’s already settled, because it’s not.” He paused, making a determined effort to if not eradicate the terse accents from his voice, then at least mute them.

Eyes closed, she tipped up her face in sensual appreciation of the sunshine. “You’ll see it my way soon enough — just give yourself time.”

Not gritting his teeth took effort. “I won’t change my mind, and contrary to your assumption, we don’t have unlimited time. For all we know, your parents might already be on their way — we need to have an agreed position before they arrive.”

At the mention of her parents, Heather turned to stare at him. Then she frowned. “I wrote and told them that I’m perfectly well, and that there’s no need for them to come all this way.”

“That may not convince them, but regardless, we need to discuss, sensibly, rationally, the prospect of a marriage between us. You may have formed an attachment to an imagined future without a wedding ring, but realistically, in our world, that isn’t an option, not for you.”

So Catriona had informed her. The weight of the rose quartz pendant against her skin reminded her of what else Catriona had said; she wasn’t therefore averse to further discussing the subject of a potential union. She faced forward. “Very well — why don’t you make your case?” And perhaps if she listened and closely observed, she might get some hint of what, beneath the words, behind his so often impassive mask, was really going on inside him. “Your case beyond the obvious social imperatives, that is.”

“Difficult given my case is based on the obvious social imperatives.”

“Nevertheless, you might at least try to find a broader foundation.”

From the corner of her eye, she saw him look up as if imploring divine aid — or perhaps more prosaically asking why me? — and had to hide a smile.

Eventually he lowered his head and leveled his hazel gaze at her. “All right — let’s try for a broader perspective. You’re a Cynster, well bred, well connected, well dowered, and more than passably attractive.”

She inclined her head. “Thank you, kind sir.”

“Don’t thank me yet. You’re also opinionated, willful to a fault, argumentative, and at times irrationally stubborn. Be that as it may, for some reason I don’t comprehend, we managed to rub along reasonably well through the last week or so, when we had a common goal. I take that as an indication that, were we to marry and jointly take on the common goal of managing my father’s estate, the estate that will in time be ours, we would again find ourselves on common ground, enough at least to make a marriage work.”

He’d surprised her.

Leaning back, she looked at him. He’d angled his shoulders into the curve of the wall, stretching one arm along the upper edge, long legs stretched out so that his boots brushed her hems. At ease, relaxed and debonair, he appeared the epitome of the sophisticated London rake, which, of course, he was.

He was also an enigma.

At some point during their hike through the mountains, she’d realized that no matter what he allowed her to see, there was something different, something even more attractive, beneath his polished veneer.

“You’d share the responsibilities of running the estate?” She hadn’t expected him to speak of such matters.

“If you wished to involve yourself with it.” He studied her face. “There are, for instance, the usual number of children to be rescued in and around the estate as you’d find anywhere else in the country.”

She humphed. “So I would remain at Baraclough, overseeing the household, while you swan about in the capital?”

Glancing down, he brushed a leaf from his breeches. “Contrary to popular belief, I don’t spend all that many weeks in the capital these days — I’m mostly at Baraclough.”

“Hmm. All right.” She nodded. “That’s something for me to consider. So what else can you tempt me with?”

Breckenridge hid a wry smile; he’d guessed that, in common with her female Cynster mentors, she’d be drawn to the prospect of managing a large household and the estate’s people. Organizing ran in the blood. “I believe I mentioned that I’m under sisterly edict to marry. Unsurprisingly, a large and pertinent motive behind my sisters’ prodding is the desirability of me begetting an heir, or more, thus securing the succession. Perish the thought the estate might ever revert to the Crown, so you could view your role as my future countess as in part holding the ton line against King George and his cronies.”

She narrowed her eyes on his. “That’s the most inventive way I’ve ever heard of saying you want children.”

His lips curved, then he let the expression fade. “I do — but do you?”

She looked forward. “Yes, of course.” After a moment she added, “I can’t imagine not wanting children, truth be told.”

“Well, then, we’re in agreement on that.”

“Don’t get carried away — you haven’t yet convinced me we should wed.”

He hesitated, then said, “Perhaps it’s time to examine your reasons for refusing.” He fixed his gaze on her face, once again in profile. “You’re not hesitant because of my. . for want of a better phrase ‘irregular paternity,’ are you?”

He’d thought he was asking not because he imagined she would hold that against him — he didn’t — but because it was an excellent gambit to elicit her sympathy. . yet as the words left his lips he realized that, somewhere deep inside, that question of belonging, of being seen as him and still accepted in his role, lingered.

To be banished by the look she turned on him — a frown that conveyed mystification along with incipient offense.

“Don’t be daft!” Her frown deepened. “That hadn’t even entered my head. Why would it? It’s not as if you’re not as well-born as I, and you are Brunswick’s heir, after all.” Waving back at the manor, she faced forward. “And just think of Richard.”

Heather paused, honestly stunned that he’d even imagined. . but perhaps that wasn’t it. Wasn’t the real reason he’d brought up what had to be, for him, a sensitive subject. Eyes fixed unseeing on the river, feeling her way, she went on, “You’re you — you’re too old, too experienced, too worldly to be judged by any other criteria than who and what you are.” She glanced briefly his way, encountered his customary unreadable façade. “On how you behave.”

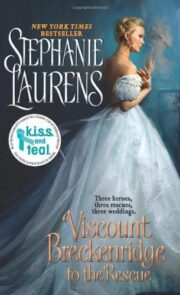

"Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue" друзьям в соцсетях.