Putting up her fan she whispered to the woman beside her: “Ninon—do you suppose that all the stories they tell about him are true?”

Ninon, perhaps a little jealous, gave Louise a look of amused scorn. “You are naive!” At that moment Charles glanced at her again; faintly he smiled.

But though he was never too much occupied to notice a pretty woman, Charles had no real interest now in anything but his sister. “How long can you stay?” was the first question he asked her when the greetings were over.

Minette gave him a rueful little smile. “Just three days,” she said softly.

Charles’s black eyes snapped and his brows drew swiftly together. “Monsieur says so?”

“Yes.” Her voice had a guilty sound, as though she were ashamed for her husband. “But he—”

“Don’t say it—I don’t want to hear you making excuses for him. But I think,” he added, “that perhaps he will reconsider.”

Monsieur reconsidered.

A messenger was back from across the Channel the next morning bringing word that Madame might remain ten days longer, provided she did not leave Dover. Minette and Charles were jubilant. Ten days! Why, it was almost an age. He was coldly furious to think that the conceited foppish little Frenchman had dared tell his sister where she might go on her holiday, but Louis sent a note asking him to respect Phillipe’s wishes in this matter, for Monsieur had learned of the treaty and might talk indiscreetly if angered too far.

Queen Catherine and all the ladies of the Court came down from London, and with the brief time he had Charles set about doing what he could to make the dismal little sea-coast village into a place fit for the entertainment of the person he loved best on earth. Dover Castle was cold and dark and damp, with the scant furnishings of feudal austerity; but it came alive again when the walls were hung with lengths of golden cloth; and scarlet and sapphire and vivid green banners streamed down from the windows. But even the Castle was not large enough to house them all and lords and ladies of both Courts were quartered in cottages or crammed into inns.

These inconveniences did not trouble anyone, and through every hour ran the noisy laughter and gay high spirits of a Court on holiday. Gilt coaches rattled through the narrow rocky little street. Handsomely gowned women and men in perukes and embroidered coats were seen in the tight courtyards, in the public-rooms of taverns and inns. Life was a continuous round of plays and banquets, balls at night and magnificent collations. While they danced and gambled flirtations sprang up like green shoots after rain between French ladies and English gentlemen, French gentlemen and English ladies. The gossip was that Madame had come to England for the very solemn purpose of laughing the English out of their own styles and back into French ones—temporarily discarded during the War—and that set the tone of the festivities.

Yet the plots and intrigues went on. They could no more be suspended, even temporarily, than could the force of gravity—for they were what held the Court together.

It took only a few days to get the treaty signed; it had been in preparation more than two years and there was little left to do but put the signatures to it. Arlington and three others signed for England, de Croissy for France.

For Charles it marked the successful culmination of ten years of planning. French money would free him, in part at least, from his Parliament; French men and ships would help him to the defeat of his country’s most dangerous enemy, the Dutch. In return he gave nothing but a promise—a promise that one day, at his own convenience, he would declare himself a Catholic. Charles was much amused to see how eager the French envoy was to complete the business, how eager they were to pay him for protection against a war he had never intended to wage.

“If everything I’ve ever done,” he said to Arlington, when it was signed and complete, “dies when I die—at least I’ll leave England this much. This treaty is a promise that one day she’ll be the greatest nation on earth. Let my French cousin have the Continent if he wants it. The world is wide, and when we’ve destroyed the Dutch all the seas on it will belong to England.”

Arlington, who sat with one weary hand pressed to his aching head, sighed a little. “I hope she’ll be grateful, Sire.”

Charles grinned, shrugged his shoulders, and reached down to give him a friendly pat. “Grateful, Harry? When was a nation or a woman ever grateful for the favours you do her? Well—I think my sister’s abed now; I always pay her a call last thing at night. You’ve been working too hard these past few days, Harry. Better take a sleeping-potion and have a good night’s rest.” He went out of the room.

He found Minette sitting up waiting for him in the enormous canopied four-poster bed. The last of her waiting-women were straggling out, and half-asleep on her lap was her little tan-and-black spaniel, Mimi. He took a chair beside her and for a moment they sat silent, smiling, looking at each other. Charles reached out one hand and covered both her own.

“Well,” he said. “It’s done.”

“At last. I can scarcely believe it. I’ve worked hard for this, my dear—because I thought it was what you wanted. Louis has often accused me of minding your interests more than his own.” She laughed a little. “You know how tender his pride is.”

“I think it’s more than pride, Minette—don’t you?” His smile teased her, for rumours still persisted that Louis had been madly in love with her several years before and had not yet quite recovered.

But she did not want to talk about that. “I don’t know. My brother—there’s something you must promise me.”

“Anything, my dear.”

“Promise me that you won’t declare your Catholicism too soon.”

A look of surprise came into Charles’s eyes, but was quickly gone. His face seldom betrayed him. “Why do you say that?”

“Because the King is troubled about it. He’s afraid you may declare yourself and alienate the German Protestant princes-he needs them when we fight Holland. And he fears that the English people would not tolerate it—he thinks that the best time would be in the midst of a victorious war.”

An almost irresistible smile came to Charles’s mouth, but he forced it back.

So Louis thought that the English people would not tolerate a Catholic king—and was afraid that a revolution in England might spread to France. He regarded his French cousin with a kind of amused contempt, but was glad it was always possible to hoodwink him. Charles had never intended and did not now intend to try to force Catholicism on his people—of course they would not tolerate it—and he preferred to keep his throne. It was his expectation to die quietly in his bed at Whitehall.

Nevertheless he answered Minette seriously, for even she did not share all his secrets. “I won’t declare myself without consulting his interests. You may tell him so for me.”

She smiled, and her little hand pressed his affectionately. “I’m glad—for I know how much it means to you.”

Almost ashamed, he quickly lowered his eyes.

I know how much it means to you, he repeated to himself. How much it means—He made a fervent wish that it would always mean as much to her as it did now. He did not want her ever to know what it was to believe in nothing, to have faith in nothing. He looked up again. His eyes brooded over her, his dark face earnest and unsmiling.

“You’re thin, Minette.”

She seemed surprised. “Am I? Why—perhaps I am.” She looked down at herself and as she moved the spaniel gave a resentful little grunt, telling her to be still. “But I’ve never been plump, you know. You’ve always called me ‘Minette.’”

“Are you feeling well?”

“Why, yes, of course.” She spoke quickly, like one who hates to tell a lie. “Oh—perhaps a headache now and then. I may be a little tired from all the excitement. But that will soon pass.”

His face hardened slowly. “Are you happy?”

Now she looked as though he had trapped her. “Mon Dieu! What a question! What would you say if someone asked you, ‘Are you happy?’ I suppose I’m as happy as most people. No one is ever truly happy, do you think? If you get even half of what you want from life—” She gave a little shrug and gestured with one hand. “Why, that’s all one can hope for, isn’t it?”

“And have you got half of what you wanted from life?”

She glanced away from him, down at the ornate carved footboard of the bed; her fingers stroked through Mimi’s scented glossy coat. “Yes, I think I have. I have you—and I have France: I love you both—” She looked up with a sudden wistful little smile. “And I think that both of you love me.”

“I do love you, Minette. I love you more than anyone or anything on earth. I’ve never thought that many men are worth a friendship or many women worth a man’s love. But with you it’s different, Minette. You’re all that matters in the world to me—”

Her eyes took on a mischievous sparkle. “All that matters to you? Come now, you can’t really mean that when you have—”

He answered her almost roughly. “I’m not jesting. You’re all I have that matters to me—These other women—” He shrugged. “You know what they’re for.”

Minette shook her head gently. “Sometimes, my brother, I’m almost sorry for your mistresses.”

“You needn’t be. They love me as little as I love them. They get what they want, and most of them more than they’re worth. Tell me, Minette—how has Philippe treated you since the Chevalier’s banishment? Every Englishman who visits France brings back tales about his behaviour to you that make my blood run cold. I regret the day you married that malicious little ape.” His black eyes gleamed with cold loathing and as he set his teeth the muscles of his jaw flexed nervously.

Minette answered him softly and there was a look of almost maternal pity on her face. “Poor Philippe. You mustn’t judge him too hard. He really loved the Chevalier. When Louis sent him away I was afraid that Philippe would go out of his mind—and he thought that I was responsible for his banishment. To tell you the truth I’d be glad enough to have him back again—it would make my own life much more peaceful. And Philippe’s so jealous of me. He suffers agonies when someone even compliments a new gown I’m wearing. He was half wild when he learned I was to take this trip—you’ll never believe it but he slept with me every night, hoping I’d become pregnant and the trip would have to be postponed again.” She laughed a little at that, though it was a laugh without much mirth. “That’s how desperate he was. It’s strange,” she continued reflectively, “but before we were married he thought that he was in love with me. Now he says it turns his stomach to think of getting into bed with a woman. Oh, I’m sorry, my dear,” she said swiftly, seeing how white he had become, so white that a queer almost grey pallor showed through the bronze tones of his skin. “I never meant to tell you these things. It doesn’t matter, really. There are so many other things in life that are delightful—”

Suddenly Charles’s face contorted with a painful spasm and he bent his head, covering his eyes with the heels of his two hands. Minette, alarmed, reached over to touch him.

“Sire,” she said softly. “Sire, please. Oh, forgive me for talking like a fool!” She flung the little spaniel aside and hastily got out of bed to stand beside him, her arms about his shoulders; then she knelt in front of him, but his face was hidden from her. “My dear—look at me, please—” She took hold of his wrists and though at first he resisted her, slowly she dragged his hands down. “My brother!” she cried then. “Don’t look like that!”

He gave a heavy sigh; all at once his face relaxed. “I’m sorry. But I swear I could kill him with my bare hands! He won’t treat you like that any more, Minette. Louis will see that his brother mends his ways, or I’ll tear that damned treaty into bits!”

In the little room, draperies of scarlet and gold embroidered with the emblem of the house of Stuart had been hung to cover the stone walls. Candelabra with masses of tapers were lighted, for though it was mid-afternoon it was dark indoors because there were no windows—only one or two narrow slits placed very high. A heavy stench of perfumes and stale sweat clogged the nostrils. Voices were low and respectfully murmurous, fans whispered in languid hands, half-a-dozen fiddlers played soft tender music.

Only Charles and Minette occupied chairs—most of the others stood, though some of the men sat on thick cushions scattered over the floor. Monmouth had taken one just at his aunt’s feet and he sat with his arms clasped about his knees, looking up at her with a face full of frank adoration. Everyone had fallen in love with Minette all over again, willing victims to her sweetness and charm, her ardent wish to be liked, the quality she had in common with her oldest brother which made people love her without knowing why.

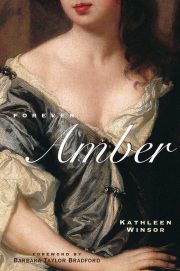

"Forever Amber" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Forever Amber". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Forever Amber" друзьям в соцсетях.