“I want to give you something,” she was saying to Charles, “to remember me by.”

“My dear—” His mouth had a whimsical smile. “As though I’m likely to forget you.”

“But let me make you a little gift. Perhaps a little jewel—something you can put on sometimes that will make you think of me—” She turned her head and spoke to Louise de Kerouaille who was standing just at her shoulder. Louise was never far from Minette when the King was in the room. “My dear, will you bring me my jewel-box—it’s in the center drawer of that cabinet.”

Louise made a delicate little curtsy; all her movements were graceful and pretty. She had a kind of well-bred diffidence, a refinement and an easy elegance which Charles admired in women but seldom found combined in the gustier ladies of his own Court. She was Parisian to the last fibre of her body, the last thread of her gown. And though she had undeniably flirted with him she had never been brazen or tactless or bold—she was a woman who must be won before she might be possessed. Charles, quite thoroughly jaded, was piqued at the notion of being once more the pursuer, not the pursued.

As she stood now before Minette, holding the box in her two hands, he said: “Here’s the jewel I want—Let her stay in England, Minette.”

Louise blushed, very becomingly, and lowered her eyes. Several of the English ladies stiffened perceptibly. The Duchess of Ravenspur and the Countess of Castlemaine exchanged indignant glances—for all the English mistresses had been allied against Louise from the first moment they had seen her. Amused and subtle smiles appeared on the faces of the men. But Minette shook her head.

“I’m responsible to her parents, Sire. They trust me to bring her back.” And then, to smooth over the awkward moment, she added: “Here—whatever you like—whatever will make you think most often of me.”

Charles smiled suavely, not at all offended or embarrassed, and made a selection from the trinkets in the box. Within a moment he seemed to have completely forgotten the episode. But he had not at all. Someday, he promised himself, I’ll have that woman—and his memory was often as long in such matters as it was short in others.

At that moment the Queen entered with several of her ladies, among whom the Duchess of Richmond was always to be found these days. Since Frances’s disfigurement by small-pox she and Catherine had become ever faster friends, until now she hung about her Majesty with a kind of trustful pathetic dependence in which the lords and ladies of Whitehall found cause only for contemptuous amusement.

Minette left the next day.

Charles, ’with York and Monmouth and Rupert, went on board the French ship and sailed partway out into the Channel. From the moment he had seen her he had been dreading this hour of parting; now he felt that he could not bring himself to let her go. For he had a mortal fear that he would never see her again. She looked tired; she looked disillusioned; she looked ill.

Three times he said goodbye, but each time he returned to embrace her once more. “Oh, my God, Minette!” he muttered at last. “I can’t let you go!”

Minette had tried not to cry, but now the tears rolled down her cheeks. “Remember what you promised me. And remember that I love you and that I’ve always loved you better than anyone else on earth. If I don’t see you again—”

“Don’t say that!” Inadvertently he gave her a little shake. “Of course I’ll see you again! You’re coming back next year—Promise me—promise me, Minette!”

Minette tipped back her head and smiled at him, her face suddenly cleared and peaceful. Like an obedient child she repeated after him, “I’m coming back next year—I promise—”

CHAPTER SIXTY–EIGHT

AMBER HAD BEEN almost as annoyed as Charles that Monsieur insisted upon Minette remaining in Dover—for she had not wanted to leave London. Until the last moment she hesitated, but when the Queen set out she went along. All the fortnight of Minette’s visit, however, she was unhappy and ill-at-ease. She wanted desperately to go back to London, to try someway, any way she could, to see him again. She was passionately relieved when the French fleet set sail and Minette was on her way home.

She had no more than entered the Palace—where she kept and often occupied her old suite—when she sent a footboy to discover Lord Carlton’s whereabouts. Impatience and nervousness made her irritable and she found fault with everything as she waited, criticized the gown Madame Rouvière had just completed, complained that she had been jolted to a jelly by that infernal coachman who was to be discharged at once, and swore she had never seen such a draggle-tail slut as that French cat, de Kerouaille.

“What’s keeping that little catch-fart!” she demanded furiously at last. “He’s been gone two hours and more! I’ll baste his sides for this!” And just then, hearing his quiet “Madame—” behind her, she whirled about. “Well, sirrah!” she cried. “How now? Is this the way you serve me?”

“I’m sorry, your Grace. They told me at Almsbury House his Lordship was down at the wharves.” (Bruce’s ship had made two round trips to and from America since last August and he was now getting them ready to sail a third time. On the next trip back they would put into a French port and he and Corinna would sail from there with the furniture they intended to buy in Paris.) “But when I got there he was nowhere to be found. They thought he had gone to dine with a City merchant and did not know whether he would return later today or not.”

Amber glowered sullenly at the floor, her right hand clasping the back of her neck. She was desperately worried, she was agonizingly disappointed, and to add to her troubles she had begun to suspect that she was pregnant again. If she was, she was sure that the child must be Lord Carlton’s, and though she longed to tell him, she dared not. She knew also that she should see Dr. Fraser and ask him to put her into a course of physic, but could not bring herself to do it.

“Her Ladyship is at home,” said the footboy now, eager to be of some help.

“What if she is!” cried Amber. “That’s nothing to me! Go along now and don’t trouble me any more!”

He bowed his way out respectfully but Amber had turned her back on him and was absorbed in her own worries and plans. She was determined to see him again—it made no difference how, and she cared not at all that he only too obviously did not wish to see her. Unexpectedly the words of the little footboy came back to her. “Her Ladyship is at home.” He had not been gone a minute when she snapped her fingers and whirled around.

“Nan! Send to have the coach got ready again! I’m going to call on my Lady Carlton!” Nan stared at her for an instant, dumfounded, and Amber gave an angry clap of her hands. “Don’t stand there with your mouth half-cocked! Do as I say and be quick about it!”

“But, madame,” protested Nan. “I just sent to have the coachman discharged!”

“Well, send again to catch him before he leaves. I must use him for today at least.”

She was hurrying about to gather her muff and gloves, mask and fan and cloak, and she left the room close on Nan’s heels. Susanna came running up from the nursery at that moment, having just been told that her mother was back, and Amber knelt to give her a hasty squeeze and a kiss, then told her that she must be off. Susanna wanted to go along and when Amber refused she began to cry and finally stamped her foot, very imperious.

“I will too go!”

“No, you won’t, you saucy minx! Be still now, or I’ll slap you!”

Susanna stopped crying all at once and gave her a look of such hurt and bewildered astonishment—for usually her mother made a great fuss over her when she had been gone a few days and always brought back a present of some kind—that Amber was instantly contrite. She knelt and took her into her arms again, kissed her tenderly and smoothed her hair and promised her that she might come upstairs that night to say her prayers. Susanna’s eyes and face were still wet but she was smiling when Amber waved goodbye.

But as she sat waiting for Corinna in the anteroom outside their apartments Amber began to wish she had not come.

For if Bruce should return and find her there she knew that he would be furious—it might undo whatever chance she still had left to make up the quarrel with him. She felt sick and cold, trembling inside, at the mere thought of confronting this woman. The door opened and Corinna came in, a faint look of surprise on her face as she saw Amber sitting there. But she curtsied and said politely that it was kind of her to call. She invited her to come into the drawing-room.

Amber got up, still hesitating on the verge of giving some random excuse and running away—but when Corinna stepped aside she walked before her into the drawing-room. Corinna had on a flowing silk dressing-gown in warm soft tones of rose and blue. Her heavy black hair fell free over her shoulders and down her back, there were two or three tuberoses pinned into it and she had another cluster of her favourite flower fastened at her bosom.

Oh, how I hate you! thought Amber with sudden savagery. I hate you, I despise you! I wish you were dead!

It was obvious too that Corinna, for all her smooth and charming manners, liked her visitor no better. She had lied when she had told Bruce that she did not believe he had continued to see her—and now the mere sight of this honey-haired amber-eyed woman filled her with loathing. She had almost come to believe that while both of them lived neither could ever be truly at peace. Their glances caught and for a moment they looked into each other’s eyes: mortal enemies, two women in love with the same man.

Amber, realizing that she must say something, now remarked with what casualness she could: “Almsbury tells me you’ll be sailing soon.”

“As soon as possible, madame.”

“You’ll be very glad to leave London, I suppose?”

She had not come for simpering feminine compliments, insincere smiles and subtly disguised cuts; now her tawny speckled eyes were hard and shining, ruthless as those of a cat watching its prey.

Corinna returned her stare, not at all disconcerted or intimidated. “I shall, indeed, madame. Though perhaps not for the reason you suppose.”

“I don’t know what you mean!”

“I’m sorry. I thought you would.”

Amber’s claws came out at that. You bitch, she thought. I’ll pay you off for that. I know a way to make you sweat.

“You’re looking mighty smug it seems to me, madame—for a woman whose husband is unfaithful to her.”

Corinna’s eyes widened incredulously. For a moment she was silent, then very quietly she said, “Why did you come here, madame?”

Amber leaned forward in her chair, holding tightly to her gloves with both hands, eyes narrowed and voice low and intense. “I came to tell you something. I came to tell you that whatever you may think—he loves me still. He’ll always love me!”

Corinna’s cool answer astonished her. “You may think so if you like, madame.”

Amber sprang up out of her chair. “I may think so if I like!” she jeered. Swiftly she crossed the few feet of floor between them and was standing beside her. “Don’t be a fool! You won’t believe me because you’re afraid to! He never stopped seeing me at all!” Her excitement was mounting dangerously. “We’ve been meeting in secret—two or three times a week—at a lodging-house in Magpie Yard! All the afternoons you thought he was hunting or at the theatre he was with me! All the nights you thought he was at Whitehall or at a tavern we were together!”

She saw Corinna’s face turn white and a little muscle twitched beside her left eye. There! thought Amber with a fierce surge of pleasure. She felt that one, I’ll wager! This was what she had come for: to bait her, to prod her most sensitive emotions, to humiliate her with boasting of Bruce’s infidelity. She wanted to see her cringe and shrink. She wanted to see a woman who looked as miserable, as badly beaten as she felt.

“Now what d’you make of his fidelity to you!”

Corinna was staring at her, a kind of repugnant horror on her face. “I don’t think there’s any shred of honourable feeling left in you!”

Amber’s mouth twisted into an ugly sneer; she did not realize how unpleasant she looked, but was past caring if she had. “Honour! What the devil is honour! A bogey-man to scare children! That’s all it’s good for these days! You can’t think what a fool you’ve looked to all of us these past months—we’ve been laughing in our fists at you—Oh, never deceive yourself—he’s laughed with the rest of us!”

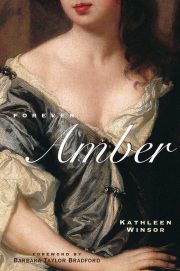

"Forever Amber" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Forever Amber". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Forever Amber" друзьям в соцсетях.