Mavis has darted ahead. Before the others have a chance to tromp their boots through my bedroom, she has rushed in and collected my treasures. Father’s pocket watch, my brother’s and my christening cups, the lace collar I have been straining my eyes and fingers over these empty evenings. But most important is my scrapbook. I shudder to think of Aunt Clara’s fat fingers picking through its pages. Perched on top of my possessions, in an offering of solidarity, is a photograph of Mavis, plain as a platter in her Sunday best. I will add it to my book when I have more than a moment to myself.

The room is tiny and airless and fitted with a narrow bed, an iron nightstand, and one dreary dormer window. Quinn had called it his rookery, and he’d relished its perch high above the family. I don’t feel the same way.

I exchange my candle for Toby’s little silver cup, and I wedge myself into the windowsill, bumping my head on the eave. My temples pound, my lips are dry, my mouth tastes of ash. I stare out at the tar black sky.

“Toby,” I whisper. “Is he with you?”

In answer, silence. But I know I’m not alone. A ghost will find his way home. I learned this nine months ago when my brother died in a field hospital in Stevensburg, Virginia. I was in the parlor that day, using the last light to cut linen strips for the Boston Ladies’ Aid. Toby’s presence was a wave crashing over me, knocking the breath from my body. Three days later we received the letter.

Many people have asked me if it’s strange to be a twin. I’d say it is far more peculiar to be a single twin. I was Toby’s alter and his double, and we created shelters for each other in the physical world. In life he’d been shy, and his death before he’d seen a day of combat was a quiet end to an innocent young life.

And yet in death Toby isn’t ready to go, or to let me go. We used to predict our futures on scraps of paper in the downstairs coat cupboard. When I stare into the eyes of his photograph, which is safely tucked inside my scrapbook, I can hear his whisper in my head, confiding his dreams to spy for the Union and regaling me with stories of Nathan Hale and how wars are won through ciphers and invisible ink. “A spy sees everyone, but is seen by no one,” he loved to say. “Remember that, Jennie.”

Other times, like now, he keeps silent, but I sense him. He guards me in spirit just he as did in the physical world. He has brought me closer to the other side, and I know that I’m changed.

“Please, a tiny sign,” I whisper, my hands clasping the cup like a chalice, “if Will is really dead and gone.”

“Who’s there?” Mavis has rushed into the room with armloads of my clothing. Her gaze jumps around the darkest corners of the room.

“Nobody. I was…praying,” I fib, hiding the cup from sight, and then we’re both self-conscious. Mavis makes a business of hanging my dresses in the single cupboard and folding some of my personal items into its top drawer. As I pace the room, worrying the frayed sleeve of my dressing gown between my fingers, I catch sight of myself in the window’s dark reflection. My hair springs wild from my head, and there is a stunned look in my eyes, as if I am not quite available to receive the news that I’m dreading to hear.

“Quinn is settled?” I ask.

She smothers a yawn and nods. “Doctor Perkins sent him to bed with a grain of morphine. Everyone says it’s rest he needs most, but oh, Miss Jennie, he’s got so thin, hasn’t he? Just the bones of his old self.”

“I think Will is gone forever.”

“Now, why would you say such a thing?” Mavis genuflects, then points the same finger on me, accusing. “Like you know something.”

I hadn’t meant to say such a thing. I hadn’t meant to speak at all.

“But you’re awful cold, Miss.” She catches my hand and squeezes, as though it’s she who frightened me, and not the other way around. “I’ll build up a fire.” She drops to kneel before the grate, steepling nubs of kindling. “And I’ll fetch you the rest of your clothing come morning,” she murmurs, “though you ought to be downstairs in the yellow room.” She strikes the match and sits back on her heels as the flame catches.

“Aunt Clara’d have given me the yellow room if I’d asked for it.” The hour is late, and I’m drained, but Mavis is a delicate soul, led often to fears and tears. “It’ll be pleasant roosting up here near you. Nobody to pester us.”

She attempts a smile. “Not Missus Sullivan, anyways. She sleeps like the dead, specially if she’d nipped into the cooking sherry. You’ll hear the mice, too. They get ornery when they’re hungry.” She waves off the phosphorus and steps back to watch the fire crackle. “I’m awful sorry, Miss. It pains me. This room’s not fit for the lady of the house.”

“I’m not the lady of this house.”

“Soon you will be, and everyone knows it. He’ll come back to you. By the New Year, I’ll predict.” She’s predicting a miracle.

I look down, and my fingers find my ring, which twinkles in the firelight like an extravagant and sentimental hope.

My tears will come later, I’m sure. Right now, I don’t want to believe it. I want to wake up from it.

3.

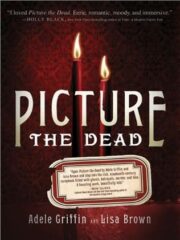

"Picture the Dead" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Picture the Dead". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Picture the Dead" друзьям в соцсетях.