I wake with a pit in my stomach. I wish I could yank up my quilts and hide from the day, but the morning doesn’t know to mourn. The winter sun smiles over my view of the kitchen garden. Hannibal struts the fence, sounding his imperious crow. Aunt Clara’s clipped holly bushes are interspersed with hellebores, all blooming in obedient array.

I’ll bring Quinn some flowers. An innocent excuse to pay him a not-so-innocent visit, but I need to hear him say it out loud. Of the two brothers, Quinn was more often the subject of Toby’s and my whispered confidences. We were cowed by his coolly impeccable demeanor and hurt by his ice-pick wit. Will was easier either warmly, sweetly happy or in a hot temper. Nothing in between, nothing to hide.

“Even if Quinn thinks we’re low and unschooled,” Toby once declared, “I wish he’d do a better job of pretending he didn’t.” As we got older, we avoided our cousin rather than shrivel under his scorn.

Quinn’s bedroom door is shut. I hesitate as my eyes land on a photograph hanging in the corridor. It had been commissioned of the brothers last spring, and in their summer suits they make quite a pair. Aunt enjoyed celebrating her handsome sons, both of whom she swore had the Emory chin, the Emory nose if pressed, she would avow that Quinn and Will possessed the Emory everything, with Uncle Henry offering scant more than his surname.

I tap. And then again. Even when I creak open the door, Quinn doesn’t turn. He lies in bed like a prince on his tomb. His bandages are an unwieldy crown. But he’s awake. I jump to hear him speak my name.

“Yes,” I tell him. “I’m here.”

“You hate me, don’t you?” he says without looking at me.

I am startled that my cousin would care what I think. “Don’t be ridiculous.” I place the vase so he can see it. The morning light is stark. I can barely recognize my returned cousin. Mavis was right he is a living skeleton.

“Mrs. Sullivan says it might snow later today. But it appears that Mavis has already stocked enough firewood to keep you warm.” I add another birch log to the fire, but the chill has seeped inside my bones.

“You wished I were Will. Last night I could see it in your face. You wished he’d come home instead of me.” He scowls. “Mother’s joy doesn’t make up for your devastation.”

“No, you can’t ”

“And why wouldn’t you mourn? My brother was your beloved, and now I’m your enemy even if you’ll never admit it. I convinced him to sign up with the Twenty-eighth, and I failed my most important duty, to bring him back alive.”

“He’s gone, then.” I force him to confirm it. “He’s been killed.”

“Yes.”

I’d been braced for this truth, but I’m not sure I ever would have been prepared for it. The air leaves my lungs. It takes all my resilience to walk across the room and slip my hand into Quinn’s. He is suffering, too, after all.

His palms are calloused, chapped. Gentleman’s hands no more. “Quinn, tell me. How did it happen? I’m strong enough to stand it.”

“If I’m strong enough to tell it.” He swallows. “Undo my bandage first. And bring me a mirror. I want to see my eye.”

“But Doctor Perkins ”

His head jerks up from the pillow. “If it were your eye, you’d snap your fingers for a mirror and command me not to bully you.”

Quinn hasn’t lost his uncanny ability to pin me to my own logic, but I’m too weak to spar with him. I retrieve the hand mirror from the bureau. Then I sit close and begin the odious task of unwinding his bandages. My attention is grave and utter, and for a few minutes there’s no other sound than our breathing.

I thought I’d been ready, but a scream fills the cavity of my body as I peel back the last blood-crusted layer and let the cloth fall from my fingers.

In the flinted symmetry of his face, Quinn’s wound is monstrous. Bruise-blackened, his eyelid raw as bitten plum, the whites of his eye filled with blood. He takes the mirror and stares at himself, then puts it down and looks at me, his head tilted like a hawk. Quinn was so beautiful. How he must suffer this mutilation. I pinch my thigh through my skirts as I return his gaze.

“It must have been terrifying to be shot,” I say. The tremble in my voice betrays me. I sense his dare for me to keep looking.

“It was, but this wound’s not from gunfire. It was Will who took the bullet.” Quinn’s words are hammered flat, though there’s density of emotion behind them. “That’s all you want to hear about anyway. On May sixth. It pierced his lung. We’d been fighting in Virginia, southeast of where we lost Toby. A special pocket of hell called the Wilderness.” His hand slips under his pillow and pulls out an envelope, thin as a moth wing.

I open it. The paper of the telegram is creased and blotchy, but the writing is legible enough to see what matters. The message is signed by a Captain James Fleming.

I refold it and return it to Quinn, vowing to come back for it later. I’m not stealing; I need it for my scrapbook. It’s evidence, a dossier fit for the spy that Toby had so desperately wanted to become. In the months since his death, I’ve been honing my skills. Toby was an astute observer. He never got lost; he could see like a hawk. Now it is up to me to adapt these habits. If I’d been his brother instead of his sister, I’d have stepped firm into Toby’s boots and charged out the door in a heartbeat to join the infantry, becoming the Union scout he wanted to be.

But this telegram, which I’ll tuck alongside Will’s dog-eared letters home, are mostly evidence of a life cut too short. I hold my spine straight. The least I can do is not break down in Quinn’s presence when he’s had to carry the burden of this news.

Still, my mind is spinning back through time. My last letter from Will had been postmarked the third of May. He has been dead all these months. How could I not have sensed it? How could I be so vain as to presume that I would have? Inexplicably, I’m furious with my twin. Why does Toby shadow me if he can’t serve as a messenger between worlds?

“Was he in terrible pain?”

“Not so much as shock.”

“And you were with him in the end? Or did he die alone?”

“I was with him. Of that I can attest.”

“Did he…did he have any last words?” For me, I add, silently. I feel tears and blink them back.

“He went pretty quick, Jennie.”

“What of his things? Things he carried ” I’m thinking of the necklace that I’d given to Will before he’d left, a silver chain and heart-shaped locket, inside which his miniature faced mine. Will had promised that he’d wear it next to his skin every day and that, dead or alive, the locket and chain would one day return to me. But I don’t quite dare speak of it particularly, lest Quinn think me even more selfish than he already does, utterly absorbed in my own loss.

“I’ve got nothing,” he says. “Other soldiers stole us blind before we’d got to the Wilderness…our watches, my belt buckle, my spurs. It happens. We all joined up so dumb and green, nobody thought… nobody expected ” His voice breaks off.

On impulse, I reach out and smooth his hair, gingery brown and long enough to curl around his ears. It’s uncommonly soft, like kitten fur. I don’t think I’ve ever touched him before. His skin burns under my fingers, as though with fever. Quinn flinches but doesn’t move out of reach.

“There’s a new kind of quiet in this house,” he says softly. “It bothered me all last night. It kept me up, and when I did sleep, I dreamed myself back into other times, like last Christmas. Remember last Christmas, Jennie? The four of us together skating on Jamaica Pond, and all our cracking-fun snowball fights, and how we carved our initials in the bark of that butternut tree?”

I smile. “Of course.” The memories warm me like a sip of brandy in an ice storm. “And you’re right. It’s been too quiet here. And so lonely,” I confess. “I’ve missed you all of you a thousand different times a day. All of these months with only Aunt and Uncle have been enough to drive me mad.”

Suddenly Quinn’s hand wraps hard around my wrist. He grips me tight, his bones shifting around mine. I wince, but he won’t let me go. “Jennie, promise not to listen to gossip.”

“What gossip?” His hand doesn’t loosen. Fear holds me in place. “What do you mean? Is there something else I need to hear? Because I’d rather it come from you than the servants.”

“Only what I’ve said. War changed us. We always meant to be decent. We meant to do right. The dead cannot defend themselves, but surely they have paid enough.”

“Of course,” I murmur.

He releases me, but Quinn has a secret he’s not telling.

The dead cannot defend themselves. It’s hard to imagine William Pritchett being less than absolutely decent, or doing anything that he needed to explain. Boisterous, spirited Will, who loved nothing better than camping and fishing and sleeping under the stars, was tailor-made for military life. Could he have changed so much?

“Don’t say anything to Mother. Let me be the one to give her the news.”

“She’s not a fool. She and Uncle Henry know as much by what you haven’t said.”

Quinn nods. “Send her up as soon as soon as she’s ready.”

I nod, but Quinn’s eyes are closed again. He has dismissed me.

4.

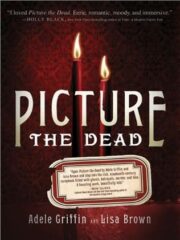

"Picture the Dead" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Picture the Dead". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Picture the Dead" друзьям в соцсетях.