Prologue

During the first fifteen years of my life, my birth and the events surrounding it were a mystery; as much a mystery as the number of stars that shone in the night sky over the bayou or where the silvery catfish hid on days when Grandpère couldn't catch one to save his life. I knew my mother only from the stories Grandmère Catherine and Grandpère Jack told me and from the few faded sepia photographs of her that we had in pewter frames. It seemed that for as long as I could remember, I always felt remorseful when I stood at her grave and gazed at the simple tombstone that read:

Gabrielle Landry

Born May 1, 1927

Died October 27, 1947

For my birth date and the date of her death were one and the same. Everyday and every night, I carried in my secret heart the ache of guilt when my birthday came around, despite the great effort Grandniece went through to make it a happy day. I knew it was as hard for her to be joyful as it was for me.

But over and above my mother's sad, sad death when I was born, there were dark questions I could never ask, even if I knew how, because I'd be much too scared it would make my grandmother's face, usually so loving, take on that closed, hooded look I dreaded. Some days she sat silently in her rocker and stared at me for what seemed like hours. Whatever the answers were, the truth had torn my grandparents to pieces; it had sent Grandpère Jack into the swamp to live alone in his shack. And from that day forward, Grandmère Catherine could not think of him without great anger flashing from her eyes and sorrow burning in her heart.

The unknown lingered over our house in the bayou; it hung in the spiderwebs that turned the swamps into a jeweled world on moonlit nights; it was draped over the cypress trees like the Spanish moss that dangled over their branches. I heard it in the whispering warm summer breezes and in the water lapping against the clay. I even felt it in the piercing glance of the marsh hawk, whose yellow-circled eyes followed my every move.

I hid from the answers just as much as I longed to know them. Words that carried enough weight and power to keep two people apart who should love and cherish each other could only fill me with fear.

I would sit by my window and stare into the darkness of the swamp on a warm, spring night, letting the breeze that swept in over the swamps from the Gulf of Mexico cool my face; and I would listen to the owl.

But instead of his unearthly cry of "Who, Who, Who," I would hear him call "Why, Why, Why" and I would embrace myself more tightly to keep the trembling from reaching my pounding heart.

Book One

1

Grandmère's Powers

A loud and desperate rapping on our screen door echoed through the house and drew both my and Grandmère Catherine's attention from our work. That night we were upstairs in the grenier, the loom room, weaving the cotton jaune into blankets we would sell at the stand in front of our house on weekends when the tourists came to the bayou. I held my breath. The knocking came again, louder and more frantic.

"Go down and see who's there, Ruby," Grandmère Catherine whispered loudly. "Quickly. And if it's your Grandpère Jack soaked in that swamp whiskey again, shut the door as fast as you can," she added, but something in the way her dark eyes widened said she knew this was someone else and something far more frightening and unpleasant.

A strong breeze had kicked up behind the thick layers of dark clouds that enclosed us like a shroud, hiding the quarter moon and stars in the April Louisiana sky. This year spring had been more like summer. The days and nights were so hot and humid that I found mildew on my shoes in the morning. At noon the sun made the goldenrod glisten and drove the gnats and flies into a frenzy to find cool shade. On clear nights I could see where the swamp's Golden Lady spiders had come out to erect their giant nets for their nightly catch of beetles and mosquitos. We had stretched fabric over our windows that kept out the insects but let in whatever cool breeze came up from the Gulf.

I hurried down the stairs and through the narrow hallway that ran straight from the rear of the house to the front. The sight of Theresa Rodrigues's face with her nose against the screen stopped me in my tracks and turned my feet to lead. She looked as white as a water lily, her coffee black hair wild and her eyes full of terror.

"Where's your Grandmère?" she cried frantically.

I called out to my grandmother and then stepped up to the door. Theresa was a short, stout girl three years older than I. At eighteen, she was the oldest of five children. I knew her mother was about to have another. "What's wrong, Theresa?" I asked, joining her on the galerie. "Is it your mother?"

Immediately, she burst into tears, her heavy bosom heaving and falling with the sobs, her face in her hands. I looked back into the house in time to see Grandmère Catherine come down the stairs, take one look at Theresa, and cross herself.

"Speak quickly, child," Grandmère Catherine demanded, rushing up to the door.

"My mama . . . gave birth . . . to a dead baby," Theresa wailed.

"Mon Dieu," Grandmère Catherine said, and crossed herself once more. "I felt it," she muttered, her eyes turned to me. I recalled the moments during our weaving when she had raised her gaze and had seemed to listen to the sounds of the night. The cry of a raccoon had sounded like the cry of a baby.

"My father sent me to fetch you," Theresa moaned through her tears. Grandmère Catherine nodded and squeezed Theresa's hand reassuringly.

"I'm coming right away."

"Thank you, Mrs. Landry. Thank you," Theresa said, and shot off the porch and into the night, leaving me confused and frightened. Grandmère Catherine was already gathering her things and filling a split-oak basket. Quickly, I went back inside.

"What does Mr. Rodrigues want, Grandmère? What can you do for them now?"

When Grandmère was summoned at night, it usually meant someone was very sick or in pain. No matter what it was, my stomach would tingle as if I had swallowed a dozen flies that buzzed around and around inside.

"Get the butane lantern," she ordered instead of answering. I hurried to do so. Unlike the frantic Theresa Rodrigues whose terror had lit her way through the darkness, we would need the lantern to go from the front porch and over the marsh grass to the inky black gravel highway. To Grandmère the overcast night sky carried an ominous meaning, especially tonight. As soon as we stepped out and she looked up, she shook her head and muttered, "Not a good sign."

Behind us and beside us, the swamp seemed to come alive with her dark words. Frogs croaked, night birds cawed, and gators slithered over the cool mud.

At fifteen I was already two inches taller than Grandmère Catherine who was barely five-feet-four in her moccasins. Diminutive in size, she was still the strongest woman knew, for besides her wisdom and her grit, she carried the powers of a Traiteur, a treater; she was a spiritual healer, someone unafraid to do battle with evil, no matter how dark or insidious that evil was. Grandmère always seemed to have a solution, always seemed to reach back in her bag of cure-alls and rituals and manage to find the proper course of action. It was something unwritten, something handed down to her, and whatever was not handed down, she magically knew herself.

Grandmère was left-handed, which to all of us Cajuns meant she could have spiritual powers. But I thought her power came from her dark onyx eyes. She was never afraid of anything. Legend had it that one night in the swamp she had come face-to-face with the Grim Reaper himself and she'd stared down Death's gaze until he realized she was no one to tangle with just yet.

People in the bayou came to her to cure their warts and their rheumatism. She had her secret medicines for colds and coughs and was said even to know a way to prevent aging, although she never used it because it would be against the natural order of things. Nature was sacred to Grandmère Catherine. She extracted all of her remedies from the plants and herbs, the trees and animals that lived near or in the swamps.

"Why are we going to the Rodrigues house, Grandmère? Isn't it too late?"

"Couchemal," she muttered, and mumbled a prayer under her breath. The way she prayed made my spine tingle and, despite the humidity, gave me a chill. I clenched my teeth together as hard as I could, hoping they wouldn't chatter. I was determined to be as fearless as Grandmère, and most of the time I succeeded.

"I guess that you are old enough for me to tell you," she said so quietly I had to strain to hear. "A couchemal is an evil spirit that lurks about when an unbaptized baby dies. If we don't drive it away, it will haunt the family and bring them bad luck," she said. "They should have called me as soon as Mrs. Rodrigues started her birthing. Especially on a night like this," she added darkly.

In front of us, the glow of the butane lantern made the shadows dance and wiggle to what Grandpère Jack called "The Song of the Swamp," a song not only made up of animal sounds, but also the peculiar low whistle that sometimes emerged from the twisted limbs and dangling Spanish moss we Cajuns called Spanish Beard when a breeze traveled through. I tried to stay as close to Grandmère as I could without knocking into her and my feet were moving as quickly as they could to keep up. Grandmère was so fixed on our destination, and on the astonishing task before us that she looked like she could walk through the pitch darkness.

In her split-oak basket, Grandmère carried a half-dozen small totems of the Virgin Mary, as well as a bottle of holy water and some assorted herbs and plants. The prayers and incantations she carried in her head.

"Grandmère," I began. I needed to hear the sound of my own voice. "Qu'est-ce—"

"English," she corrected quickly. "Speak only in English." Grandmère always insisted we speak English, especially when we left the house, even though our Cajun language was French. "Someday you will leave this bayou," she predicted, "and you will live in a world that maybe looks down on our Cajun language and ways."

"Why would I leave the bayou, Grandmère?" I asked her. "And why would I stay with people who looked down on us?"

"You just will," she replied in her usual cryptic manner. "You just will."

"Grandmère," I began again, "why would a spirit haunt the Rodrigueses anyway? What have they done?"

"They've done nothing. The baby was born dead. It came in the body of the infant, but the spirit was unbaptized and has no place to go, so it will haunt them and bring them bad luck."

I looked back. Night fell like a leaden curtain behind us, pushing us forward. When we made the turn, I was happy to see the lighted windows of the Butes, our closest neighbor. The sight of it allowed me to pretend that everything was normal.

"Have you done this many times before, Grandmère?" I knew my grandmother was called to perform many rituals, from blessing a new house to bringing luck to a shrimp or oyster fisherman. Mothers of young brides unable to bear children called her to do whatever she could to make them fertile. More often than not, they became pregnant. I knew of all these things, but until tonight I had never heard of a conchemal.

"Unfortunately, many times," she replied. "As did Traiteurs before me as far back as our days in the old country."

"And did you always succeed in chasing away the evil spirit?"

"Always," she replied with a tone of such confidence that I suddenly felt safe.

Grandmère Catherine and I lived alone in our toothpick-legged house with its tin roof and recessed galerie. We lived in Houma, Louisiana, which was in Terrebonne Parish. Folks said the parish was only two hours away from New Orleans by car, but I didn't know if that was true since I had never been to New Orleans. I had never left the bayou.

Grandpère Jack had built our house himself more than thirty years ago when he and Grandmère Catherine had first been married. Like most Cajun homes, our house was set on posts to keep us above the crawling animals and give us some protection from the floods and dampness. Its walls were built out of cypress wood and its roof out of corrugated metal. Whenever it rained, the drops would tap our house like a drum. The rare stranger to come to our house was sometimes bothered by it, but we were as accustomed to the drumming as we were to the shrieks of the marsh hawks.

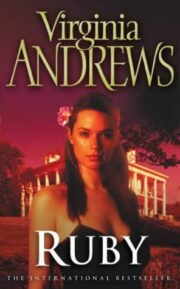

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.