"I want you to have my money, Grandmère," I told her.

"We made enough today. I don't need to take your painting money, Ruby." Then she narrowed her eyes on me. "But give it to me to hide. I know you'll feel sorry for that swamp bum and give him some if not all of it one day. I'll put it in my chest for safekeeping. He wouldn't dare look in there," she said.

Grandmère's oak chest was the most sacred thing in the house. It didn't need to be under lock and key. Grandpère Jack would never dare set his hands on it; no matter how drunk he was when he came here. Even I did not venture to open the lid and sift through the things within, for they were her most precious and personal keepsakes, including things that belonged to my mother when she was a little girl. Grandmère promised that everything in it would some day belong to me.

After we had eaten and had cleaned up, Grandmère sat in her rocking chair on the galerie, and I sat near her on the steps. It wasn't as muggy and hot as the night before because there was a brisk breeze. The sky had only a few scattered clouds so the bayou was well lit by the yellowish white light of the moon. It made the limbs of the trees in the swamp look like bones and the still water glisten like glass. On a night like this, sounds traveled over the bayou quickly and easily. We could hear the happy tunes coming from Mr. Bute's accordion and the laughter of his wife and children, all gathered on their front galerie. Somewhere, way in the distance down left toward town, a car horn blared, while behind us, the frogs croaked in the swamp. I had not told Grandmère Catherine that Paul was coming, but she sensed it.

"You look like you're sitting on pins and needles tonight, Ruby. Waiting for something?"

Before I could reply, we heard the soft growl of Paul's motor scooter.

"No need to answer," Grandmère said. Moments later, we saw the small light on his motor scooter, and Paul rode into our front yard.

"Good evening, Mrs. Landry," he said, walking up to us. "Hi, Ruby."

"Hello," Grandmère Catherine said, eying him cautiously.

"We have a little relief from the heat and humidity tonight," he said, and she nodded. "How was your day?" he asked me.

"Wonderful! I sold all five of my paintings," I declared quickly.

"All of them? That is wonderful. We'll have to celebrate with two ice cream sodas instead of just crushed ice. If it's all right with you, Mrs. Landry, I'd like to take Ruby to town," he added, turning to Grandmère Catherine. I saw how his request troubled her. Her eyebrows rose and she leaned back in her rocker. Her hesitation made Paul add, "We won't be long."

"I don't want you to take her on that flimsy motor thing," Grandmère said, nodding toward the scooter. Paul laughed.

"I'd rather walk on a night like this anyway, wouldn't you, Ruby?"

"Yes. All right, Grandmère?"

"I suppose. But don't go anywhere but to town and back and don't talk to any strangers," she cautioned.

"Yes, Grandmère."

"Don't worry, I won't let anything happen to her," Paul assured Grandmère. Paul's assurance didn't make her look less anxious, but he and I started toward town, our way well lit by the moon. He didn't take my hand until we were out of sight.

"Your Grandmère worries so much about you," Paul said. "She's seen a lot of sadness and hard times. But we had a good day at the stall."

"And you sold all your paintings. That's great."

"I didn't sell them so much as get them into a New Orleans gallery," I said, and told him everything that had happened and what Dominique LeGrand had said.

Paul was silent for a long moment. Then he turned to me, his face strangely sad. "Someday, you'll be a famous artist and move away from the bayou. You'll live in a big house in New Orleans, I'm sure," he predicted, "and forget all us Cajuns."

"Oh, Paul, how could you say such a horrible thing? I'd like to be a famous artist, of course; but I would never turn my back on my people and . . . and never forget you. Never," I insisted.

"You mean that, Ruby?"

I tossed my hair back over my shoulder and put my hand on my heart. Then, closing my eyes, I said, "I swear on Saint Medad. Besides," I continued, snapping my eyes open, "it will probably be you who leaves the bayou to go to some fancy college and meet wealthy girls."

"Oh, no," he protested. "I don't want to meet other girls. You're the only girl I care about."

"You say that now, Paul Marcus Tate, but time has a way of changing things. Look at my grandparents. They were once in love."

"That's different. My father says no one could live with your grandfather."

"Once, Grandmère did," I said. "And then things changed, things she never expected."

"They won't change with me," Paul boasted. He paused and stepped closer to take my hand again. "Did you ask your grandmother about the fais dodo?"

"Yes," I said. "Can you come to dinner tomorrow night? I think she should have a chance to get to know you better. Could you?"

He was quiet for a long moment.

"Your parents won't let you," I concluded.

"I'll be there," he said. "My parents are just going to have to get used to the idea of you and me," he added, and smiled. Our eyes remained firmly on each other and then he leaned toward me and we kissed in the moonlight. The sound and sight of an automobile set us apart and made us walk faster toward the town and the soda shop.

The street looked busier than usual this evening. Many of the local shrimp fishermen had brought their families in to enjoy the feast at the Cajun Queen, a restaurant that advertised an all-you-can-eat platter of crawfish and potatoes with pitchers of draft beer. In fact, there was a real festive atmosphere with the Cajun Swamp Trio playing their accordion, fiddle, and washboard on the comer near the Cajun Queen. Peddlers were out and folks sat on cypress log benches watching the parade of people go by. Some were eating beignets and drinking from mugs of coffee and some were feasting on sea bob, which was dried shrimp, some-times called Cajun Peanuts.

Paul and I went to the soda fountain and confectionery store and sat at the counter to have our ice cream sodas. When Paul told the owner, Mr. Clements, why we were celebrating, he put gobs of whip cream and cherries on top of our sodas. I couldn't remember an ice cream soda that had ever tasted as good. We were having such a good time, we almost didn't hear the commotion outside, but other people in the store rushed to the door to see what was happening and we soon followed.

My heart sunk when I saw what it was: Grandpère Jack being thrown out of the Cajun Queen. Even though he had been escorted out, he remained on the steps waving his fist and screaming about injustice.

"I'd better see if I can persuade him to go home and calm down," I muttered, and hurried out. Paul followed. The crowd of onlookers had begun to break up, no longer much interested in a drunken man babbling to himself on the steps. I pulled on the sleeve of his jacket.

"Grandpère, Grandpère ."

"Wha . . .who . . ." He spun around, a trickle of whiskey running out of the corner of his mouth and down the grainy surface of his unshaven chin. For a moment he wobbled on his feet as he tried to focus on me. The strands of his dry, crusty looking hair stood out in every direction. His clothing was stained with mud and bits of food. He brought his eyes closer. "Gabrielle?" he said.

"No, Grandpère. It's Ruby, Ruby. Come along, Grandpère. You have to go home. Come along," I said. It wasn't the first time I had found him in a drunken stupor and had to urge him to go home. And it wasn't the first time he had looked at me with his eyes hazy and called me by my mother's name.

"Wha . . ." He looked from me to Paul and then back at me again. "Ruby?"

"Yes, Grandpère. You must go home and sleep."

"Sleep, sleep? Yeah," he said, turning back toward the Cajun Queen. "Those no good . . . they take your money and then when you voice your opinion about somethin' . . . things ain't what they was around here, that's for sure, that's for damn sure."

"Come on, Grandpère." I tugged his hand and he came off' the steps, nearly tripping and falling on his face. Paul rushed to take hold of his other arm.

"My boat," Grandpère muttered. "At the dock." Then he turned and ripped his hand from mine to wave his fist at the Cajun Queen one more time. "You don't know nothin’. None of you remember the swamp the way it was 'fore these damn oil people came. Hear?"

"They heard you, Grandpère. Now it's time to go home."

"Home. I can't go home," he muttered. "She won't let me go home."

I swung my gaze to Paul who looked very upset for me. "Come along, Grandpère," I urged again, and he stumbled forward as we guided him to the dock.

"He won't be able to navigate this boat himself," Paul declared. "Maybe I should just take him and you should go home, Ruby."

"Oh, no. go along. I know my way through the canals better than you do, Paul," I insisted.

We got Grandpère into his dingy and sat him down. Immediately, he fell over the bench. Paul helped him get comfortable and then he started the motor and we pulled away from the dock, some of the people still watching us and shaking their heads. Grandmère Catherine would hear about this quickly, I thought, and she would just nod and say she wasn't surprised.

Minutes after we pulled away from the dock, Grandpère Jack was snoring. I tried to make him more comfortable by putting a rolled up sack under his head. He moaned and muttered something incoherently before falling asleep and snoring again. Then I joined Paul.

"I'm sorry," I said.

"For what?"

"I'm sure your parents will find out about this tomorrow and be angry."

"It doesn't matter," he assured me, but I remembered how dark Grandmère Catherine's eyes had become when she asked me what his parents thought of his seeing me. Surely they would use this incident to convince him to stay away from the Landrys. What if signs began to appear everywhere saying, "No Landrys Allowed," just like Grandmère Catherine described from the past? Perhaps I really would have to flee from the bayou to find someone to love me and make me his wife. Perhaps this was what Grandmère Catherine meant.

The moon lit our way through the canals, but when we went deeper into the swamp, the sad veils of Spanish moss and the thick, intertwined leaves of the cypress blocked out the bright illumination making the waterway more difficult to navigate. We had to slow down to avoid the stumps. When the moonlight did break through an opening, it made the backs of the gators glitter. One whipped its tail, splash-ing water in our direction as if to say, you don't belong here. Farther along, we saw the eyes of a marsh deer lit up by the moonbeams. We saw his silhouetted body turn to disappear in the darker shadows.

Finally, Grandpère's shack came into view. His galerie was crowded with nets for oyster fishing, a pile of Spanish moss he had gathered to sell to the furniture manufacturers who used it for stuffing, his rocking chair with the accordion on it, empty beer bottles and a whiskey bottle beside the chair and a crusted gumbo bowl. Some of his muskrat traps dangled from the roof of the galerie and some hides were draped over the railing. His pirogue with the pole he used to gather the Spanish moss was tied to his small dock. Paul gracefully navigated us up beside it and shut off the motor of the dingy. Then we began the difficult task of getting Grandpère out of the boat. He offered little assistance and came close to spilling all three of us into the swamp.

Paul surprised me with his strength. He virtually carried Grandpère over the galerie and into the shack. When I turned on a butane lamp, I wished I hadn't. Clothing was strewn all about and everywhere there were empty and partially empty bottles of cheap whiskey. His cot was unmade, the blanket hanging down with most of it on the floor. His dinner table was covered with dirty dishes and crusted bowls and glasses, as well as stained silverware. From the expression on his face, I saw that Paul was overwhelmed by the filth and the mess.

"He'd be better off sleeping right in the swamp," he muttered. I fixed the cot so he could lower Grandpère Jack onto it. Then we both started to undo his hip boots. "I can do this," Paul said. I nodded and went to the table first to clear it off and put the dishes and bowls into the sink, which I found to be full of other dirty dishes and bowls. While I washed and cleaned, Paul went around the shack and picked up the empty cans and bottles.

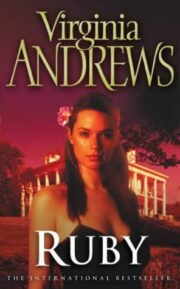

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.