I knew Grandmère Catherine would be upset that I was traveling alone through the swamp this later in the summer day, as well as being upset that I was going to see Grandpère Jack. But my anger had come to a head and sent me rushing out of the house to plod over the marsh and pole the pirogue faster than ever. Before long, I came around a turn and saw Grandpère's shack straight ahead. But as I approached, I slowed down because the racket coming from it was frightening.

I heard pans clanging, furniture cracking, Grandpère's howls and curses. A small chair came flying out the door and splashed in the swamp before it quickly sunk. A pot followed and then another. I stopped my canoe and waited. Moments later, Grandpère appeared on his galerie. He was stark naked, his hair wild, holding a bullwhip. Even at this distance, I could see his eyes were bloodshot. His body was streaked with dirt and mud and there were even long, thin scratches up his legs and down the small of his back.

He cracked the whip at something in the air before him and shouted before cracking it again. I soon understood he was imagining some kind of creature and I realized he was having a drunken fit. Grandmère Catherine had described one of them to me, but I had never seen it before. She said the alcohol soaked his brain so bad it gave him delusions and created nightmares, even in the daytime. On more than one occasion, he had one of these fits in the house and destroyed many of their good things.

"I used to have to run out and wait until he grew exhausted and fell asleep," she told me. "Otherwise, he might very well hurt me without realizing it."

Remembering those words, I backed my canoe into a small inlet so he wouldn't see me watching. He cracked the whip again and again and screamed so hard, the veins in his neck bulged. Then he caught the whip in some of his muskrat traps and got it so entangled, he couldn't pull it out. He interpreted this as the monster grabbing his whip. It put a new hysteria into him and he began to wail, waving his arms about him so quickly, he looked like a cross between a man and a spider from where I was watching. Finally, the exhaustion Grandmère Catherine described set in and he collapsed to the porch floor.

I waited a long moment. All was silent and remained so. Satisfied, he was unconscious, I poled myself up to the galerie and peered over the edge to see him twisted and asleep, oblivious to the mosquitos that feasted on his exposed skin.

I tied up the canoe and stepped onto the galerie. He looked barely alive, his chest heaving and falling with great effort. I knew I couldn't lift him and carry him into the house, so I went inside and found a blanket to put over him.

Then, I pulled in a deep fearful breath and nudged him, but his eyes didn't even flutter. He was already snoring. I went cold inside. All the hopes that had lit up were snuffed out by the sight and the stench rising off him. He smelled like he had taken a bath in his jugs of cheap whiskey.

"So much for coming to you for any help, Grandpère," I said furiously. "You are a disgrace." With him unconscious, I was able to vent my anger unchecked. "What kind of a man are you? How could you let us struggle and strain to keep alive and well? You know how tired Grandmère Catherine is. Don't you have any self-respect?

"I hate having Landry blood in me. I hate it!" I screamed, and pounded my fists against my hips. My voice echoed through the swamp. A heron flew off instantly and a dozen feet away, an alligator lifted its head from the water and gazed in my direction. "Stay here, stay in the swamp and guzzle your rotgut whiskey until you die. I don't care," I cried. The tears streaked down my cheeks, hot tears of anger and frustration. My heart pounded.

I caught my breath and stared at him. He moaned, but he didn't open his eyes. Disgusted, I got back into the pirogue and started to pole myself home, feeling more despondent and defeated than ever.

With the tourist trade nearly nonexistent and school over, I had more time to do my artwork. Grandmère Catherine was the first to notice that my pictures were remarkably different. Usually in a melancholy mood when I began, I tended now to use darker colors and depict the swamp world at either twilight or at night with the pale white light of a half moon or full moon penetrating twisted sycamores and cypress limbs. Animals stared out with luminous eyes and snakes coiled their bodies, poised to strike and kill any intruders. The water was inky, the Spanish moss dangling over it like a net left there to ensnare the unwary traveler. Even the spiderwebs that I used to make sparkle like jewels now appeared more like the traps they were intended to be. The swamp was an eerie, dismal, and depressing place and if I did include my mysterious father in the picture, he had a face masked with shadows.

"I don't think most people would like that picture, Ruby," Grandmère told me one day as she stood behind me and watched me visualize another nightmare. "It's not the kind of picture that will make them feel good, the kind they're going to want to hang up in their living rooms and sitting rooms in New Orleans."

"It's how I feel, what I see right now, Grandmère. I can't help it," I told her.

She shook her head sadly and sighed before retreating to her oak rocker. I found she spent more and more time sitting and falling asleep in it. Even on cloudy days when it was a bit cooler outside, she no longer took her pleasure walks along the canals. She didn't care to go find wild flowers, nor would she visit her friends as much as she used to visit them. Invitations to lunch went unaccepted. She made her excuses, claimed she had to do this or that, but usually ended up falling asleep in a chair or on the sofa.

When she didn't know I was watching, I caught her taking deep breaths and pressing her palm against her bosom. Any exertion, washing clothes or the floors, polishing furniture, and even cooking exhausted her. She had to take frequent rests in between and battle to catch her breath.

But when I asked her about it, she was always ready with an excuse. She was tired from staying up too late the night before; she had a bit of lumbago, she got up too fast, anything and everything but her owning up to the truth—that she hadn't been well for quite some time now.

Finally, on the third Sunday in August, I rose and dressed and went down, surprised I was up and ready before her, especially on a church day. When she finally appeared, she looked pale and very old, as old as Rip van Winkle after his extended sleep. She cringed a bit when she walked and held her hand against her side.

"I don't know what's come over me," she declared. "I haven't overslept like this for years."

"Maybe you can't cure yourself, Grandmère. Maybe your herbs and potions don't work on you and you should see a town doctor," I suggested.

"Nonsense. I just haven't found the right formula yet, but I'm on the right track. be back to myself in a day or two," she swore, but two days went by and she didn't improve an iota. One minute she would be talking to me and the next, she would be fast asleep in her chair, her mouth wide open, her chest heaving as if it were a struggle to breathe.

Only two events got her up and about with the old energy she used to exhibit. The first was when Grandpère Jack came to the house and actually asked us for money. I was sitting with Grandmère on the galerie after our dinner, grateful for the little coolness the twilight brought to the bayou. Her head grew heavier and heavier on her shoulders until her chin'-rested on her chest, but the moment Grandpère Jack's footsteps could be heard, her head snapped up. She narrowed her eyes into slits of suspicion.

"What's he coming here for?" she demanded, staring into the darkness out of which he emerged like some ghostly apparition from the swamp: his long hair bouncing on the back of his neck, his face sallow with his grimy gray beard thicker than usual, and his clothes so creased and dirty, he looked like he had been rolling around in them for days. His boots were so thick with mud, it looked caked around his feet and ankles.

"Don't you come any closer," Grandmère snapped. "We just had our dinner and the stink will turn our stomachs."

"Aw, woman," he said, but he stopped about a half-dozen yards from the galerie. He took off his hat and held it in his hands. Fishhooks dangled from the brim. "I come here on a mission of mercy," he said.

"Mercy? Mercy for who?" Grandmère demanded.

"For me," he replied. That nearly set her laughing. She rocked a bit and shook her head.

"You come here to beg forgiveness?" she asked.

"I came here to borrow some money," he said.

"What?" She stopped rocking, stunned.

"My dingy's motor is shot to hell and Charlie McDermott won't advance me any more credit to buy a new used one from him. I gotta have a motor or I can't earn any money guiding hunters, harvesting oysters, whatnot," he said. "I know you got something put away and I swear—"

"What good is your oath, Jack Landry? You're a cursed man, a doomed man whose soul already has a prime reservation in hell," she told him with more vehemence and energy than I had seen her exert in days. For a moment Grandpère didn't reply.

"If I can earn something, I can pay you back and then some right quickly," he said. Grandmère snorted.

"If I gave you the last pile of pennies we had, you'd turn from here and run as fast as you could to get a bottle of rum and drink yourself into another stupor," she told him. "Besides," she said, "we haven't got anything. You know how times get in the bayou in the summer for us. Not that you showed you cared any," she added.

"I do what I can," he protested.

"For yourself and your damnable thirst," she fired back.

I shifted my gaze from Grandmère to Grandpère. He really did look desperate and repentant. Grandmère Catherine knew I had my painting money put away. I could loan it to him if he was really in a fix, I thought, but I was afraid to say.

"You'd let a man die out here in the swamp, starve to death and become food for the buzzards," he moaned.

She stood up slowly, rising to her full five feet four inches of height as if she were really six feet tall, her head up, her shoulders back, and then she lifted her left arm to point her forefinger at him. I saw his eyes bulge with shock and fear as he took a step back.

"You are already dead, Jack Landry," she declared with the authority of a bishop, "and already food for buzzards. Go back to your cemetery and leave us be," she commanded.

"Some Christian you are," he cried, but continued to back up. "Some show of mercy. You're no better than me, Catherine. You're no better," he called, and turned to get swallowed up in the darkness from where he had come as quickly as he had appeared. Grandmère stared after him a few moments even after he was gone and then sat down.

"We could have given him my painting money, Grandmère," I said. She shook her head vehemently.

"That money is not to be touched by him," she said firmly. "You're going to need it someday, Ruby, and besides," she added, "he'd only do what I said, turn it into cheap whiskey.

"The nerve of him," she continued, more to herself than to me, "coming around here and asking me to loan him money. The nerve of him . . ."

I watched her wind herself down until she was slumped in her chair again, and I thought how terrible it was that two people who had once kissed and held each other, who had loved and wanted to be with each other were now like two alley cats, hissing and scratching at each other in the night.

The confrontation with my Grandpère drained Grandmère. She was so exhausted, I had to help her to bed. I sat beside her for a while and watched her sleep, her cheeks still red, her forehead beaded with perspiration. Her bosom rose and fell with such effort, I thought her heart would simply burst under the pressure.

That night I went to sleep with great trepidation, afraid that when I woke up, I would find Grandmère Catherine hadn't. But thankfully, her sleep revived her and what woke me the next morning was the sound of her footsteps as she made her way to the kitchen to start breakfast and begin another day of work in the loom room.

Despite the lack of customers, we continued our weaving and handicrafts whenever we could during the summer months, building a stock of goods to put out when the tourist season got back into high swing. Grandmère bartered with cotton growers and farmers who harvested the palmetto leaves with which we made the hats and fans. She traded some of her gumbo for split oak so we could make the baskets. Whenever it appeared we were bone-dry and had nothing to offer in return for craft materials, Grandmère reached deeper into her sacred chest and came up with something of value she had either been given as payment for a traiteur mission years before, or something she had been saving just for such a time.

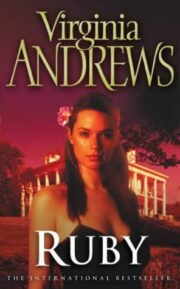

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.