6

Room in My Heart

"If you knew who my father was all this time, Grandmère, why didn't you tell me? Where does he live? How did I get a sister? Why did it have to be kept such a secret, and why did this drive Grandpère into the swamp to live?" I fired my questions, one after the other, my voice impatient.

Grandmère Catherine closed her eyes. I knew it was her way to gather strength. It was as if she could reach into a second self and draw out the energy that made her the healer she was to the Cajun people in Terrebonne Parish.

My heart was thumping, a slow, heavy whacking in my chest that made me dizzy. The world around us seemed to grow very still. It was as if every owl, every insect, even the breeze was holding its breath in anticipation. After a moment Grandmère Catherine opened her dark eyes, eyes that were now shadowed and sad, and fixed them on me firmly as she shook her head ever so gently. I thought she released a soft moan before she began.

"I've dreaded this day for so long," Grandmère said, "dreaded it because once you've heard it all, you will know just how deeply into the depths of hell and damnation your Grandpère has gone. I've dreaded it because once you've heard it all you will know how much more tragic than you ever dreamed was your mother's short life, and I've dreaded it because once you've heard it all, you will know how much of your life, your family, your history, I have kept hidden from you.

"Please don't blame me for it, Ruby," she pleaded. "I have tried to be more than your Grandmère. I have tried to do what I thought was best for you.

"But at the same time," she continued, gazing down at her hands in her lap for a moment, "I must confess I have been somewhat selfish, too, for I wanted to keep you with me, wanted to keep something of my poor lost daughter beside me." She gazed up at me again. "If I have sinned, God forgive me, for my intentions were not evil and I did try to do the best I could for you, even though I admit, you would have had a much richer, much more comfortable life, if I had given you up the day you were born."

She sat back and sighed again as if a great weight had begun to be lifted from her shoulders and off her heart.

"Grandmère, no matter what you've done, no matter what you tell me, I will always love you just as I always have loved you," I assured her.

She smiled softly and then grew thoughtful and serious again.

"The truth is, Ruby, I couldn't have gone on; I would never have had the strength, even the spiritual strength I was born to have, if you hadn't been with me all these years. You have been my salvation and my hope, as you still are. However, now that I'm drawing closer and closer to the end of my days here, you must leave the bayou and go where you belong."

"Where do I belong, Grandmère?"

"In New Orleans."

"Because of my artwork?" I said, nodding in anticipation of her response. She had said it so many times before.

"Not only because of your talent," she replied, and then she sat forward and continued. "After Gabrielle had gotten herself into trouble with Paul Tate's father, she became a very withdrawn and solitary person. She didn't want to attend school anymore no matter how much I begged, so that except for the people who came around here, she saw no one. She became something of a wild thing, a true part of the bayou, a recluse who lived in nature and loved only natural things.

"And Nature accepted her with open arms. The beautiful birds she loved, loved her. I would look out and see how the marsh hawks watched over her, flew from tree to tree to follow her along the canals.

"She would always return with beautiful wild flowers in her hair when she went for a walk that lasted most of the afternoon. Gabrielle could spend hours sitting by the water, dazzled by its ebb and flow, hypnotized by the songs of the birds. I began to think the frogs that gathered around her actually spoke to her.

"Nothing harmed her. Even the alligators maintained a respectful distance, holding their eyes out of the water just enough to gaze at her as she walked along the shores of the marsh. It was as if the swamp and all the wildlife within it saw her as one of their own.

"She would take our pirogue and pole through those canals better than your Grandpère Jack. She certainly knew the water better, never getting hung up on anything. She went deep into the swamp, went to places rarely visited by human beings. If she had wanted to, she could have been a better swamp guide than your Grandpère," Grandmère added, nodding.

"As time went by, Gabrielle became even more beautiful. She seemed to draw on the natural beauty around her. Her face blossomed like a flower, her complexion was as soft as rose petals, her eyes were as bright as the noonday sunlight streaming through the goldenrod. She walked more softly than the marsh deer, who were never afraid to come right up to her. I saw her stroke their heads myself," Grandmère said, smiling warmly, deeply at her vivid memories, memories I longed to share.

"There was nothing sweeter to my ears than the sound of Gabrielle's laughter, no jewel more sparkling than the sparkle of her soft smile.

"When I was a little girl, much younger than you are now, my Grandmère told me stories about the so-called swamp fairies, nymphs that dwelled deep in the bayou and would show themselves only to the purest of heart. How I longed to catch sight of one. I never did, but I think I came the closest whenever I looked upon my own daughter, my own Gabrielle," she said and wiped a single fugitive tear from her cheek.

She took a deep breath, sat back, and continued.

"A little more than two years after Gabrielle's involvement with Mr. Tate, a very handsome, young Creole man came from New Orleans with his father to do some duck hunting in the swamp. In town they quickly learned about your Grandpère, who was, to give the devil his due," she muttered, "the best swamp guide in this bayou.

"This young man, Pierre Dumas, fell in love with your mother the moment he saw her emerge from the marsh with a baby rice bird on her shoulder. Her hair was long, midway down her back, and it had darkened to a rich, beautiful auburn color. She had my raven black eyes, Grandpère's dark complexion and teeth whiter than the keys of a brand-new accordion. Many a young man who had chanced by and had seen her had lost his heart quickly, but Gabrielle had become wary of men. Whenever one did stop to speak with her, she would simply toss a thin laugh his way and disappear so quickly he probably thought she really was a swamp ghost, one of my Grandmère's fairies," Grandmère Catherine said, smiling.

"But for some reason, she did not run from Pierre Dumas. Oh, he was tall and dashing in his elegant clothes, but later, she would tell me that she saw something gentle and loving in his face; she felt no threat. And I never saw a young man smitten as quickly as young Pierre Dumas was smitten. If he could have thrown off his rich clothes that very moment and gone into the swamp to live with Gabrielle then and there, he would have.

"But the truth was he was already married and had been for a little over two years. The Dumas family is one of the oldest and wealthiest families living in New Orleans," Grandmère said. "Those families guard their lineage very closely. Marriages are well thought out and arranged so as to keep up the social standing and protect their blue blood. Pierre's young wife also came from a well-respected, wealthy old Creole family.

"However, to the great chagrin of Pierre's father, Charles Dumas, Pierre's wife had been unable to get pregnant all this time. The prospect of no children was an unacceptable one to Pierre's father, and to Pierre as well. But they were good Catholics and divorce was not an alternative. Neither was adopting a child, for Charles Dumas wanted the Dumas blood to run through the veins of all of his grandchildren.

"Weekend after weekend, Pierre Dumas and his father, more often, just Pierre, would visit Houma and go duck hunting. Pierre began to spend more time with Gabrielle than he did with Grandpère Jack. Naturally, I was very worried. Even if Pierre wasn't already married, his father would not want him to bring back a wild Cajun girl with no rich lineage. I warned Gabrielle about him, but she simply looked at me and smiled as if I were trying to stop the wind.

"Pierre would never do anything to hurt me," she insisted. "Soon, he was coming and not even pretending his purpose was to hire Grandpère Jack to guide him on a hunting trip. He and Gabrielle would pack a lunch and go off in the pirogue, deep into the swamp to places only Gabrielle knew."

Grandmère paused in her tale and stared down at her hands again for a long moment. When she looked up again, her eyes were full of pain.

"This time Gabrielle didn't tell me she was pregnant. She didn't have to. I saw it in her face and soon saw it in her stomach. When I confronted her about it, she simply smiled and said she wanted Pierre's baby, a child she would bring up in the bayou to love the swamp world as much as she did. She made me promise that no matter what happened, I would make sure her child lived here and learned to love the things she loved. God forgive me, I finally gave in and made such a promise, even though it broke my heart to see her with child and to know what it would do to her reputation among our own people.

"We tried to cover up what had happened by telling the story about the stranger at the fais dodo. Some people accepted it, but most didn't care. It was just another reason why they should look down on the Landrys. Even my best friends smiled when they faced me, but whispered behind my back. Many a family I had helped with my healing, contributed to the gossip."

Grandmère took a deep breath before she continued, seeming to draw the strength she needed out of the air.

"Unbeknownst to me, your Grandpère and Pierre's father had met to discuss the impending birth. Your Grandpère had already had experience selling one of Gabrielle's illegitimate children. His gambling sickness hadn't abated one bit; he still lost every piece of spare change he possessed and then some. He was in debt everywhere.

"A proposal was made some time during the last month and a half of Gabrielle's pregnancy. Charles Dumas offered fifteen thousand dollars for Pierre's child. Grandpère agreed, of course. Back in New Orleans, they were already concocting the fabrications to make it appear the child was really Pierre's wife's. Grandpère Jack told Gabrielle and it broke her heart. I was furious with him, but the worst was yet to come."

She bit down on her lower lip. Her eyes were glazed with tears, tears I was sure were burning under her eyelids, but she wanted desperately to get all of the story told before she collapsed in sorrow. I got up quickly and got her a glass of water.

"Thank you, honey," she said. She drank some and then nodded. "I'm all right." I sat down again, my eyes, my ears, my very soul fixed on her and her every word.

"Poor Gabrielle began to wilt with sorrow. She felt betrayed, but not so much by Grandpère Jack. She had always accepted his bad qualities and weaknesses the same way she accepted some of the uglier and crueler things in nature. For Gabrielle, Grandpère Jack's flaws were just the way things were, the way they were designed to be.

"But Pierre's willingness to go along with the bargain, to do what his father wanted was different. They had made secret promises to each other about the soon-to-be-born child. Pierre was going to send money to help care for the baby. He was going to visit more often. He even said he wanted the child to be brought up in the bayou where he or she would always be part of Gabrielle and her world, a world Pierre professed to love more than his own now that he had met and fallen in love with Gabrielle.

"She was so heartbroken when Grandpère Jack came to her and told her the bargain and how all the parties had agreed, that she did not put up any resistance. Instead, she spent long hours sitting in the shadows of the cypress and sycamore trees gazing out at the swamp as if the world she loved had somehow conspired to betray her as well. She had believed in its magic, worshipped its beauty and she had believed that Pierre had been won over by it as well. Now, she knew there were stronger, harder, crueler truths, the worst one being that Pierre's loyalty to his own world and his own family carried more weight with him than the promises he had made to her.

"She didn't eat well, no matter how I nagged and cajoled. I whipped up whatever herbal drinks I could to substitute for what she was missing and provide the nourishment her body needed, but she either avoided them or her depression overcame whatever value they had. Instead of blossoming in the last weeks of her pregnancy, she grew more sickly. Dark shadows formed around her eyes. She had little energy, became listless and slept most of the day away.

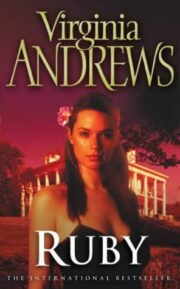

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.