"I'll be all right. You know how he gets after he has his tantrum. He'll just sleep it off and then wake up hungry and sorry for what he did."

Paul smiled, shook his head, and then reached to caress my cheek, his eyes soft and warm.

"My Ruby, always optimistic."

"Not always, Paul," I said sadly. "Not anymore."

"I'll stop by in the morning," he promised. "To see how things are."

I nodded.

"Ruby, I . . ."

"You had better go, Paul," I said. "I don't want any more nasty scenes today."

"All right." He kissed me quickly on the cheek before rising. "I'm going to talk to my father," he promised. "I'm going to get at the truth of things."

I tried to smile, but my face was like dry, brittle china from all the tears and sadness. I was afraid I might simply shatter to pieces right before his eyes.

"I will," Paul pledged at the doorway. Then he was gone.

I sighed deeply, put some of the food away, and walked upstairs to lie down again. I had never felt so tired. I did sleep through a good part of the rest of the day. If anyone came to the house, I didn't hear them. But early in the evening, I heard pots clanking and furniture being shoved around. I sat up, for a moment, very confused. Then, my wits returning, I got out of bed quickly and went downstairs to find Grandpère on his hands and knees tugging at some loose floorboards. Every cabinet door was thrown wide open and all of our pots and pans had been taken out of the cabinets and lay strewn about.

"Grandpère, what are you doing?" I asked. He turned and gazed at me with eyes I hadn't seen before, eyes of accusation and anger.

"I know she's got it hidden somewhere here," he said. "I didn't find it in her room, but I know she's got it somewhere. Where is it, Ruby? I need it," he moaned.

"Need what, Grandpère?"

"Her stash, her money. She always had a pile set aside for a rainy day. Well, my rainy days have come. I need it to get my motor fixed, to get some new equipment." He sat back on his haunches. "I got to work harder to make a go of it for both of us, Ruby. Where is it?"

"There isn't any stash, Grandpère. We were having a hard time of it, too. I once poled out to your shack to see if I could get you to help us get by, but you were collapsed on your galerie," I told him.

He shook his head, his eyes wild.

"Maybe she never told you. She was like that . . . secretive even with her own. There's a stash here somewhere," he declared, shifting his eyes from side to side. "It might take me a while, but I'll find it. If it's not in the house, it's buried somewhere outside, huh? Did you ever see or hear her diggin' out there?"

"There's no stash, Grandpère. You're wasting your time."

It was on the tip of my tongue to tell him about my art money, but it was also as if Grandmère Catherine were still there, standing right beside me, forbidding me to mention a word about it. In case he decided to look in her chest for valuables, I made a note to myself to move the money under my mattress.

"Are you hungry?" I asked him.

"No," he said quickly. "I'm going out back before it gets too dark and look some more," he said.

After he left, I put back all the pots and pans and then I warmed some food for myself. I ate mechanically, barely tasting anything. I ate just because I knew I had to in order to keep up my strength. Then, I went back upstairs. I could hear Grandpère's frantic digging in the backyard, his digging and his cursing. I heard him ripping through the smokehouse and even banging around in the outhouse. Finally, he grew exhausted with the searching and came back inside. I heard him get himself something to eat and drink. His frustration was so great, he moaned like a calf that had lost its mother. Soon, he was talking to ghosts.

"Where'd you put the money, Catherine? I got to have the money to take care of our granddaughter, don't I? Where is it?"

Finally, he grew quiet. I tiptoed out and looked over the railing to see him collapsed at the kitchen table, his head on his arms. I returned to my room and I sat by my window and gazed up at the horned moon half hidden by dark clouds and I thought, this is the same moon that rode high over New Orleans, and I tried to imagine my future. Would I be rich and famous and live in a big house some day like Grandmère Catherine predicted?

Or was all that just a dream, too? Just another web, dazzling in the moonlight, a mirage, an illusion of jewels woven in the darkness, waiting, full of promises that were as empty and as light as the web itself?

There was no period in my life when I thought time passed more slowly than it did during the days following Grandmère Catherine's funeral and burial. Every time I looked at the old—and tarnished brass clock set in its cherry wood case on the windowsill in the loom room and saw that instead of an hour only ten minutes had passed, I was surprised and disappointed. I tried to fill my every moment, keep my hands and my mind busy so I wouldn't think and remember and mourn, but no matter how much work I did and how hard I worked, there was always time to remember.

One memory that returned with the persistence of a housefly was my recollection of the promise I had made to Grandmère Catherine should anything bad happen to her. She had reminded me of it the day she had died and she had forced me to repeat my vow. I had promised not to stay here, not to live with Grandpère Jack. Grandmère Catherine wanted me to go to New Orleans and find my real father and my sister, but the very thought of leaving the bayou and getting on a bus to go to a city that loomed as far away and as strange to me as a distant planet was terrifying. I was positive I would stand out as clearly as a crawfish in a pot of duck gumbo. Everyone in New Orleans would take one look at me and say to himself, "There's an ignorant Cajun girl traveling on her own." They would laugh at me and mock me for sure.

I had never traveled very far, especially on my own, but it wasn't the fear of the journey, nor even the size of the city and the unfamiliarity with city life that frightened me the most. No, what was even more terrifying was imagining what my real father would do and say as soon as I presented myself. How would he react? What would I do if he shut the door in my face? After having deserted Grandpère Jack and then, after having been rejected by my father, where would I go?

I had read enough about the evils of city life to know about the horrors that went on in the slums, and the terrible fates young girls such as myself suffered. Would I become one of those women I had heard about, women who were taken into bordellos to provide men with sexual pleasures? What other sort of work would I be able to get? Who would hire a young Cajun girl with a limited education and only simple handicraft skills? I envisioned myself ending up sleeping in some gutter, surrounded by other downcast and downtrodden people.

No, it was easier to put off the promise and lock myself upstairs in the grenier for most of the day, working on the linens and towels as if Grandmère Catherine were still alive and just downstairs doing one of her kitchen chores before joining me. It was easier to pretend I had to finish something she had started while she was off on one of her traiteur missions, easier to make believe nothing had changed.

Of course, part of my day involved caring for Grandpère Jack, preparing his meals and cleaning up after him, which was an endless chore. I made him his breakfast every morning before he left to go fishing or harvesting Spanish moss in the swamp. He was still mumbling about finding Grandmère Catherine's stash and he still spent every spare moment digging and searching around the house. The longer he looked and located nothing, the more he believed I was hiding what I knew.

"Catherine wasn't one to let herself go and die and leave something buried without someone knowing where," he declared one night after he had begun to eat his supper. His green eyes darkened as he focused them on me with suspicion. "You didn't dig somethin' up and hide it where I've already looked, have you, Ruby? Wouldn't surprise me none to learn that Catherine had told you to do just such a thing before she died."

"No, Grandpère. I've told you time after time. There was no stash. We had to spend everything we made. Before Grandmère died, we were depending on what she got from some of her traiteur missions, too, and you know how much she hated taking anything for helping people." What my eyes must have shown convinced him I was not lying, at least for the time being.

"That's jus' it," he said, chewing thoughtfully, "people gave her things, gave her money, too, I'm sure. I just wonder if she left anything with one of those busybodies, 'specially that Mrs. Thibodeau. One of these nights, I might pay that woman a visit," he declared.

"I wouldn't do that, Grandpère," I warned him.

"Why not? The Money don't belong to her; it belongs to me . . . us that is."

"Mrs. Thibodeau would call the police and have you put in jail if you so much as stepped on the floor of her galerie," I advised him. "She's as much as told me so." Once again, his piercing eyes glared my way before he went back to his food.

"All you women are in cahoots," he muttered. "A man does the best he can to keep food on the table, keep the house together. Women take all that for granted. Especially, Cajun women," he mumbled. "They think it's all coming to them. Well it ain't, and a man's got to be treated with more respect, especially in his own home. If I find that money's been hidden on me . . ."

It did no good to argue with him. I saw why Grandmère Catherine made no attempt to change the way he thought, but I did hope that in time, he would give up his frantic search for the nonexistent stash and concentrate on reforming himself the way he had promised and work hard at making a good life for us. Some days he did return from the swamp laden down with a good fish catch or a pair of ducks for our gumbo. But some days, he spent most of his time poling from one brackish pond to the next, mumbling to himself about one of his favorite gripes and then settling down in his pirogue to drink himself into a stupor, having traded his catch for a cheap bottle of gin or rum. Those nights he returned empty-handed and bitter, and I had to make do with what we had and concoct a poor Cajun's jambalaya.

Grandpère repaired some small things around the house, but left most of his other promises of work unfulfilled. He didn't patch the roof where it leaked or replace the cracked floorboards, and despite my not so subtle suggestions, he didn't improve his hygienic habits either. A week would go by before he would take a bar of soap and water to his body, and even then, it was a quick, almost insignificant rinse. Soon, there were lice in his hair again, his beard was scraggly, and his fingernails were caked with grime. I had to look at something else whenever we ate or I would lose my appetite. It was hard enough contending with the variety of sour and rancid odors that reeked from his clothes and body. How someone could let himself go like that and not care or even notice was beyond me. I imagined it had a lot to do with his drinking.

Every time I looked at the portrait I had done of Grandmère Catherine, I thought about returning to my painting, but whenever I set up my easel, I would just stare dumbly at the blank paper, not a creative thought coming to mind. I attempted a few starts, drawing some lines, even trying to paint a simple moss-covered cypress log, but it was as if my artistic talent had died with Grandmère. I knew she would be furious even to hear such a thought, but the truth was that the bayou, the birds, the plants and trees, every-thing about it in some way made me think of Grandmère and once I did, I couldn't paint. I missed her that much.

Paul came by nearly every day, sometimes just to sit and talk on the galerie, sometimes to sit and watch me work on the loom. Often, he helped with some chore, especially a chore Grandpère should have completed before going out in the swamp for the day.

"What's that Tate boy doin’ around here so much?" Grandpère asked me late one afternoon when he returned just as Paul was leaving.

"He's just a good friend, coming around to be sure everything is all right, Grandpère," I said. I didn't have the courage to tell Grandpère I knew all the ugly truths and the terrible things he had done when my mother was pregnant with Paul. I knew how Grandpère's temper could flare, and how such revelations would just send him sucking on a bottle and then ranting and raving.

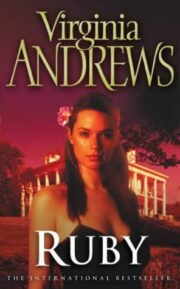

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.