“A magician never tells.”

“Please? One more time!”

He did it again. She puzzled over it and then took the match, fumbling with her fingers, unable to figure it out.

“I meant what I said about your performance,” he said. “You were stellar. Truly.”

“I can’t believe you’re saying that. Thank you so much.”

“How’d you get bitten? By the bug?”

“I was a shy kid,” she said. “My mother died when I was young, and it was hard for me. My dad got me into acting. I think he realized it could help. When I acted, I didn’t feel shy. There’s this Danny Kaye movie I saw as a kid. Wonder Man. He’s escaping from gangsters, and he winds up on the stage of an opera, mistaken for one of the performers. Every time he looks in the wings, he sees the gangsters waiting to get him. He’s only safe as long as he’s onstage. That’s kind of how I felt.”

She told Weller that when she was nine, her father had told her to audition for Elmer Rice’s Street Scene at the Potter Players, their local theater. A small role, just a few lines, but she loved every moment of the rehearsals, the blocking, the lights, and later, the period costume. When she walked onto the bright stage on opening night, she got a rush. The thrill of the moment, the potential for mishaps, the breathing of the audience, whom you could see. There was a murder toward the end of the play. Backstage, she could smell the smoke.

After the show closed, she asked her father if she could take acting class. He shuttled her to a children’s theater in Lyndonville, where she did improv drills, Shakespeare scenes, theater games, and original monologues. He suggested she try an arts camp in upstate New York. The other kids had names like Masha and Pippin and did unironic productions of Agatha Christie. In the company of these weird precocious kids, she wanted to be better.

Throughout her childhood, during school vacations or over long weekends, Jake would drive her the long six hours into the city, where they would check in to a hotel and see plays. Shanley, Ives, Albee, Wasserstein, Durang. Stephen Schwartz and Jonathan Larson, A. R. Gurney, musical revivals. Actors could create worlds out of nothing, summon real tears. They could turn psychology into behavior.

“What does your father think of the movie?” Weller asked on the patio.

“He died right after we wrapped. A heart attack.” He had been cross-country skiing alone. A guy on a snowmobile had found him.

Weller reached forward and put his hand on top of hers. “Maddy, I didn’t know. I’m so sorry.”

“It’s all right.” She didn’t like saying that, but she didn’t want to talk about it.

The day she got the call from Tanya O’Neill, their next-door neighbor, she had been on her way to an audition for a regional Room Service revival. She was walking in midtown when her cell phone rang. Tanya said only, “Your daddy . . .” Maddy knew immediately. The word “daddy.” Maddy felt like she had been shot. Because her mother had died young, it had never occurred to Maddy that her father could go early, too.

To change the subject, she said to Weller, “How did you get into acting?”

“Tenth grade, I got a knee injury during a football game,” he said. “Had to quit the team. Started getting into trouble because I had too much free time. My English teacher suggested I try out for the school production of Our Town. I read George’s monologue to Emily in the soda shop. I was blown away by the writing. That was it. I auditioned. I got George. Later, when my knee got better, I tried to do both football and acting, but I kept having to miss practice. My coach said, ‘Steve, you gonna play football or you gonna do that fag acting?’ ” Weller laughed. “I said, ‘I think I’m gonna do the acting, Coach.’ It was no contest. Acting marshaled me.”

Marshaled. Acting had marshaled her shyness, and it had marshaled his energy. He understood. Acting could save you from the pain of being yourself.

“I love acting,” he said, “but I hate most actors.”

“What’s wrong with actors?”

“Aside from the falsity and braggadocio? Most of them lack personhood. They’re stunted. And prone to illeism.”

“Illeism?”

“They speak about themselves in the third person. People who do that are missing an ‘I.’ They don’t know who they are. I prefer people who know who they are.” He was looking at her like he wanted to eat her. She looked down and then up again so she could catch her breath.

“Bridget offered to sign me,” she said. She wanted to know everything about Bridget. Whether he felt he owed his career to her.

“And what did you tell her?” he asked. His smile had deepened.

“I haven’t made up my mind. Maybe Bridget’s too big for me.”

“She wouldn’t want to work for you if she weren’t committed to helping you.”

Work for you. It was so easy to lose sight of this simple truth: If Maddy signed with her, Bridget Ostrow would be working for her, not the other way around. “Bridget was the one who discovered you, right?”

“Yep. It was the 1980s and she was one of the few women in the talent department of OTA, and she saw me in Bus Stop at the Duse Repertory Company on El Centro. That was where I got my start. We used to do eight shows a year. I learned everything from Shakespeare to Beckett to Inge. She waited by the door, and asked me to have a drink. I said no, since I was supposed to be meeting a bunch of guy buddies to watch a Tyson fight, but she went along with us. Spent the night at a sports bar. When the last friend left, she said, ‘I want to work with you.’ ”

“And what did you say?”

“I said, ‘You’re a woman. How do I know you’ll be aggressive?’ ” He chuckled. “She loves to remind me of that. I was young. I had no experience with powerful women. She said, ‘I’m twice as aggressive as any man,’ and I signed with her a week later.”

Though it seemed the kind of thing a 1980s Steven Weller would say, Maddy didn’t like that he had been so openly sexist. Maybe he enjoyed the story because it had an arc to it, or maybe he’d never said it. Celebrities told the same stories again and again, in interviews, to mold the image they wanted. At a certain point, they probably couldn’t even remember what was fact and what was fiction.

“Anyway, I hope you go with Bridget,” Weller said, getting out of the chair.

“Because you think she’s the best?” The moon made a halo around his head.

“Because then you and I might work together one day. And I’d like that.” His gaze held hers. It was an expensive gaze to put in a movie and one that looked very good blown up a thousand times.

He went inside. She turned the matchbook over in her hand but couldn’t get the trick.

In the living room, where Maddy finally found Dan, he was talking to Todd Lewitt about a tracking shot in The Widower and nodding at the answers the way Cady Pearce had nodded when Weller spoke. Maddy stood there silently, waiting for Dan to pause so she could tell him she had to talk to him, but there was never a pause. She noticed Zack enter the room, alone. She turned quickly to Dan and said, “We should be getting back,” but he shook his head.

The girl Zack had been with, now wearing a tube skirt and a sweatshirt with a print of a cat, came down a minute later, as if Zack had instructed her to delay. Zack went to the bar for more liqueur. Maddy caught herself staring at him, blushed, and turned away.

“I’m leaving,” she told Dan.

He nodded and said to Todd Lewitt, “I love Antonioni.”

She took the car back to the condo, and the driver said he would return to the party to get Dan. She went to the bathroom and rinsed her face.

And I’d like that. That look. Steven Weller seemed to have been flirting, but maybe he was playing elder statesman. Though the two weren’t mutually exclusive.

She lay on the bed and closed her eyes, but the room was spinning. She didn’t want to throw up. She paced in the living room and called Irina to tell her about Bridget, if not about Weller. It was two A.M. in New York, but Irina was a night owl. When the phone went to voice mail, Maddy hung up.

Sharoz would have advice about Bridget Ostrow. Sharoz took the Hollywood stuff in stride. She would be able to say whether Bridget Ostrow was legit or just a vanity manager for a famous man. Maddy glanced out the window at Sharoz and Kira’s condo. A light was on.

Kira opened the door in a cutoff Bad Brains T-shirt, a whiskey glass in her hand. She seemed to be weaving a little. “Hey, is Sharoz around?” Maddy asked.

“She’s at some party,” Kira said.

“Oh. Can you have her knock on my door if she comes back in the next half hour?”

“Yeah, sure.” Maddy turned unsteadily toward the door. “So how were the beautiful people?” Kira called behind her.

Dan had told Kira about the dinner invitation, and if she had been jealous, she had hidden it well. Now she seemed too tipsy to be cool. “It was a good party,” Maddy answered.

“And was the son there, the midget boy?”

“He’s not that short.”

“Oh my God, he is. I saw him in the theater for that first screening, and I was thinking how inappropriate it was that someone brought a child to our movie.”

Maddy didn’t know why she was knocking him. She was irritated with Kira for being haughty, for always undermining her. “The midget boy wants to work for me.”

“Of course he does. Did you say yes?”

“No. I don’t know what I’m going to do. You know, since you brought up the screenings, I’ve been meaning to ask you why you’ve been so obnoxious at the Q and A’s.”

“I have no idea what you’re talking about,” Kira said, her hand on her hip.

“Those comments about me being Dan’s girlfriend. You always find a way to work it in. Like I only got cast because we’re sleeping together.”

“I never said that. Is that why you think you got cast?”

“You imply it. And you’re so dismissive of my MFA. You were obnoxious during the shoot, but I never said anything because it was good for the movie. Now we’ve been lucky enough to make it here, and it’s like you have it in for me.”

“I don’t have it in for you, Maddy.”

Maddy wanted to scream. “Sure you do,” Maddy said. “You think I’m a snob.”

“God, I’ve never seen your cheeks this red except when you were doing that fucking in the movie.”

When Maddy reconstructed the moment later, it was like she was watching from a corner of the room. She shoved Kira hard, and Kira stumbled back a few steps and then strode toward her fast, like she was going to hit her. Instead, she put her face right up against Maddy’s and glared.

Without thinking about it or knowing why she was doing it, Maddy kissed her. Then she stepped back, shocked at herself and what she had done. Kira moved toward her, slowly, and touched her face. She kissed Maddy gently and with affection that seemed completely incompatible with the rudeness. Maddy’s tongue began to move in Kira’s mouth, and Kira’s hands were on Maddy’s back, pulling her closer. She could feel Kira’s breasts against her own, so much bigger than hers, these strange soft boobs in a place where until now she had encountered only hardness.

Kira was kissing her neck and her chin, and then she was unclasping Maddy’s bra and her hands were on her. Maddy cupped Kira’s breasts over the T-shirt, imagining the size and shape of her nipples. Kira lifted Maddy’s sweater and shirt over her head and went for the bra strap, and that was when Maddy realized this was happening. Dan would be home soon, wondering where she was. He might see the light on. She pulled away.

“I should go,” Maddy said. She picked up her sweater and began to put it on.

“Yeah, it’s really late.” She said it like Maddy had overstayed her welcome when only seconds ago, she had been kissing her.

Maddy felt both guilty and embarrassed. Now she had done it and she couldn’t undo it and it was her own fault, she had kissed first.

Dan didn’t get back to their condo for another hour, which gave Maddy time to shower and get into bed. It had been an otherworldly night. The dueling pitches from Bridget and Zack; then Zack with the girl; then Weller on the patio; then Kira. Maddy had never made out with a woman, not even kissed one. In the theater scene at Dartmouth, a lot of the women students got drunk and slept together, but at parties, when Maddy observed them drinking heavily and groping each other, aware that the boys were watching, it had seemed like an act. She didn’t want to do something like that just to turn on guys. Despite the occasional erotic dream about women, she believed she was ninety-five percent straight.

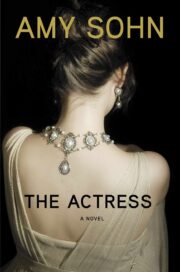

"The Actress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Actress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Actress" друзьям в соцсетях.