One of the Khakis turns to me. “Why don’t you come with us to the back? We can sort it all out there.” The gleaming new interest in his eyes unsettles me. He pretends to help me by the arm through the maze of people, but his grip is so tight I can feel his fingers dig into my flesh.

As I try to figure out how to extricate myself from the danger I’ve foolishly put myself in, the anti-aircraft guns start up. The sound of an explosion comes from outside, followed by another. The room seems to list to one side, as if the building is tipping over, as people run towards the slatted windows to peer through. A piercing whistle-like screech draws even more gawkers, and just as everyone crowds against the wall facing the street, it explodes.

A thrill passes through my body, a wild and terrified elation: I have been bombed. Then I hear the screams, see the arms and feet sticking through the rubble. The Khakis abandon their hunting game and rush to help the victims. I join in as well, in an effort to rescue two half-buried women—the white of their dresses identifies them as nurses.

I’m helping a doctor clear more fragments of wall when I feel a mouse-like movement in my salwaar. I look down to see grubby brown fingers easing out my pomegranate. It’s the boy with the Bimal Batak T-shirt. I try to seize his wrist, but he wriggles free. He scampers over the rubble towards the hole in the side of the building and I scrabble up after him. Squeezing through the opening, I follow him into the bright sunshine.

He dashes down the road, but I easily outrun him. “Leave it,” I order, catching him by the collar, but he does not obey. I grab his arm as he tries to bring the pomegranate to his mouth for a bite. “Little thug,” I say, and twist so hard that he screams and lets go. He spits at me as I retrieve the fruit from the ground, then flings a fistful of gravel in my direction and runs away.

I stand on the road to clear my head. Anti-aircraft fire still echoes in the distance, but I know the planes with the bombs have already flown away. Behind me lie the smoking remains of the Liberty, and I wonder if this is the enemy’s strategy—to destroy all the cinemas. An ancient building down the street lies in ruins as well—perhaps its tired bones have collapsed just from the trauma of witnessing the attack.

Still numb and euphoric over my bombing and escape, I head for the Marine Lines train station.

KARUN AND I got married that October at the Indica. We chose a hotel at Juhu in recognition of the picnic on the day we met. Our first choice had been the Sun ’n Sand, since it cost less, but we decided to splurge since they had no dates available until February. Uma tried to get us to have a funky ceremony on the beach itself, which I nixed. Although Karun would have preferred a court wedding, he went along with the entire priest-and-seven-circle spectacle for my mother’s sake.

The guests were almost entirely from my family’s side. When pressed to add his own invitees to the list, Karun put down the names of some of his research institute colleagues. I had been hoping to meet his long-term friends from Delhi and Karnal, but he explained it was too far to expect them to make the trip. He didn’t even have any names from his three years of college in Bombay. “I got to know some people quite well, but I’ve lost contact since.”

His only aunt took the train down from Delhi, accompanied by his two cousins. “We never thought our Karun was one to ever get married—to such a pretty bride, no less,” they said in Punjabi-flecked Hindi. “There must have been something in your Bombay water, to have so quickly cured the bachelor in him.”

Uma told me she’d tried to squeeze out information about Karun’s past, but his relatives didn’t seem that close. She was still trying to uncover evidence of a former romantic involvement—not as something to hold against him, but purely as reassurance that he was like everyone else. “All they talked about was his studiousness, how well he did in school. His aunt said he suffered from asthma after his father passed—to cure it, he took up swimming and practiced yoga every morning for an hour.”

“He still does that. Is that the best you could dredge up?”

“I’m just trying to fill in the blank pages, Sarita. Everyone’s so relieved at your marrying that they’ve checked neither background nor character—just this mad rush to get you wed. You’ve told us the story about how he accompanied you in the plunge from the diving board over and over, but have you really found out enough about him to spend your life together?”

“Of course I have. His background isn’t so mysterious—it’s not as if he comes from a long line of murderers. And we’ve talked about everything under the sun—from our favorite foods to our favorite theorems in calculus.” The calculus bit, a lie, I threw in just to provoke her: I was closer to Karun in educational grounding and way of thinking than she, with her history B.A., could ever hope to be with Anoop.

“But are you two really in love?”

“I wouldn’t be marrying him if we weren’t.”

In the four months since the diving tower, Karun and I had spent a good deal of time together. In addition to our newfound interest in cinema, we’d also started trying restaurants, especially several of the new ones that seemed to open every week in the mill area. On a day-long excursion to the amusement park at Essel World, we rode the Zyclone roller coaster four times in succession at Karun’s insistence, followed by an equal number of rides on the new Super Drop, based on Superdevi’s descent to earth after visiting the moon goddess. Our outings always felt a bit like playing hooky, as if being in each other’s company freed us from obligations, gave us dispensation to have the fun we’d never had. Karun had become both more relaxed and more expressive—by my count, we’d exchanged five “I love you’s” so far.

And yet, Uma had a point. Karun rarely put his innermost feelings on display. We hugged more than we kissed. I felt enkindled by his very presence, but the most passion he ever displayed arose while discussing physics.

“What’s the matter with you two?” Uma scolded us one day for passing up an opportunity to neck as we sat on the couch watching television. “Don’t you know the time before marriage is the best for romance?”

As I expressed mortification afterwards for my sister’s pushiness, Karun colored. “It’s I who should apologize. I’m not very good at doing what’s expected. Or even realizing what I should want. Sometimes I wonder if we’re being too hasty, if you know me well enough.”

I laughed off his words—the possibility that he might be having second thoughts alarmed me. Of course I knew him well enough—hadn’t we discussed where we’d live (Colaba), what we’d eat (home-cooked food, with lots of restaurant nights off), even how many children we’d have (exactly one—we had to create our very own trinity, after all)? Besides, didn’t millions of couples enter unions arranged by their parents, knowing each other even less? “We’re still not married,” I responded to each of Uma’s jibes. “How refreshing, for a change, to encounter someone with an excess of propriety on his part.”

To her credit, Uma ceased her doubt-raising once the day of the wedding dawned. She was the perfect sister, helping me with my jewelry and headdress, leading me to the ceremonial fire, ushering people away from the receiving line when they lingered too long. “Sarita, Sarita,” she chided, when I said goodbye at two A.M. to take the hotel elevator up to the third-floor bridal suite where Karun had retired earlier. “Don’t you know it’s the bride who’s supposed to go up first, sit waiting for the groom, blushing in bed?”

The door to the bedroom was ajar—Karun reclined on the crimson sheets draping the bed. White flowers, their petals creamy and luminous, lay scattered in a circle around his head. He must have dozed off waiting for me—he hadn’t taken off his pants, and even his shirt was still all crisply tucked in. Only his feet were bare—I noticed again the hairless ankle I’d glimpsed the morning we first met. This was the moment I’d imagined all evening as we stood on the dais, shaking hands and accepting envelopes filled with cash. Should I awaken him by gathering up the petals and sprinkling them on his face?

But he was not asleep. When I sat on the bed, he laid his head on my thigh. “Sarita,” he murmured, and opened his eyes. They were unclouded by drowsiness—instead, I noticed the sheen of anxiety in them.

“Is everything all right?”

“Yes. Of course. It’s our wedding night, why wouldn’t it be? I was just resting my eyes.”

He slid along the bed to make room for me, and I reclined, also fully clothed, next to him. We kissed quickly. His jaw was tight, his lips stretched—I’d never seen the line between them communicate such nervousness. “It’s hard to believe we’re married now, just like my parents used to be,” he said.

His tenseness had a curious effect on me—it focused my attention on trying to loosen him, making me forget my own diffidence. “Did you see the priest’s stomach? Just his belly button looked the size of a one-rupee coin. And when he put the camphor into the fire—it was all I could do not to sneeze.” I chattered on about the food and the gifts tally and the guests, and finally got him talking about his aunt.

Rather than tension, I felt a mounting anticipation. I couldn’t wait for the montage running for weeks in my mind to commence. Shedding our clothes, pressing my face into his body, feeling his kisses on my breasts. As Karun described a holiday with his cousins, I gathered up my nerve and leaned forward to arch my bosom like a bridge over his chest.

He stopped mid-sentence and lay motionless, holding his breath. Only when I unfurled my sari did he think to unhook my blouse and bra to free my breasts. I shifted my weight so that they hung like fruit over his neck. He hesitated, then leaned up to plant a kiss on each of them.

They were more chaste than I would have liked, his kisses, but I sighed my appreciation. He responded with more, apportioning them equitably between my two breasts. When I moved higher, he kissed my stomach, then stopped to wait for approval. “These wedding garments are too hot,” I said. “Let’s take some of them off.”

The cycle of cues on my part and responses on his continued after we disrobed—me to my petticoat and Karun to his underpants. I was struck by my enterprise—what had happened to my inhibition, my lack of experience? We rubbed our bodies together—he even took a breast in his mouth with my encouragement. There was something endearing about his willingness to please but also something tempering—the thought that he might not be aroused evened out the bursts of passion I felt.

Eventually, my initiatives faltered—I ran out of places to explore. I could not summon up the courage to venture uninvited below his waist. We lay side by side caressing each other. “Let’s get some rest,” I finally said, when it became clear no fire would be lit tonight.

“It’s been a long day. I’m sorry I’m so exhausted.” He buried his face in my chest to hide his embarrassment—or perhaps relief.

I turned out the light. Somehow, I didn’t feel so dejected. Although I would have liked Karun to be more assertive, I had surprised, even exhilarated, myself by taking the lead to compensate. The gentle ebb and flow of the waves outside reassured me we had many days of married life ahead.

THE ALL-CLEAR SIGNAL still hasn’t sounded, which worries me. Could the control tower for the sirens have been hit? Will people realize this and begin to eventually creep out of their holes? Or will they hunker in deeper to count out their days, convinced the silence outside heralds the end? The street lies completely empty—only an abandoned red double-decker bus looms ahead. Even the beggars who live under the bridge over Queen’s Road have disappeared—I miss running the gauntlet of their badgering voices, their pawing hands.

I mount the steps to the station. The way to tell whether trains still run is to examine the evidence left by citizens who have performed their business on the rails. Something has come by to flatten deposits, but not today. Walking looks like the best alternative, since there’s no electricity to feed the pantographs anyway. I pick my way over the tracks to the seaward side. The lawns of the line of gymkhana clubs are so unnervingly immaculate that I wonder if they still pay their gardeners to manicure each individual blade of grass. Perhaps this is the fabled sacred land the Khaki referred to, the one he dared the enemy to harm.

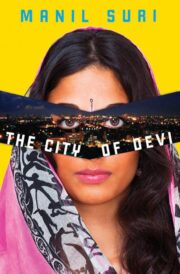

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.