I waved to Karun, but he still did not acknowledge me. I could see now that he’d folded his arms across his chest, holding them close to his body as if guarding against a chill. A chill which couldn’t exist, the sea being as warm as bathwater. “Karun,” I called, waving again, and this time, he waved back.

But he did not come to me. I stood there, wondering whether to venture in deeper. The water had already crept up my salwaar to my waist—any further, and it might begin the climb to my chest. I imagined the ride back home on the train, my clothes sticking to my skin, the outrage on my mother’s face as men crowded around to leer. I turned, half expecting her to wade in after me, all thoughts of her own clothes getting wet lost in the attempt to rescue me from shame.

Nobody stopped me. A group of children paddled by on a raft, in pursuit of a boy holding a basketball high above his head. A fully dressed woman swam purposefully through the waves, the folds of her sari ballooning around her like the whorls of a jellyfish. On the shore, I could make out the red and white segments of the umbrella under which my mother slept. In the distance, the figure of a lone child emerged from the smiling mouth of Mickey Mouse and slid down his inflated tongue.

I took another step in. A large wave, its head irate and foamy, slammed into my groin. I staggered, and for an instant wondered if I should fall. Surely then Karun would have to run to me. I would be drenched, but the distance between us would be dissolved. Would he reach into the water and pull me up in his arms?

Before I could further evaluate this ploy, he came sloshing up to me. “Do you like to swim? It’s something I’ve loved ever since my teens.”

Could this be the criterion he’d set for a spouse—someone aquatically adept? I thought back to all those wasted swimming sessions at school, spent splashing around in the shallow end of the pool. “I never did learn.” The confession brought with it that sinking feeling of having skipped over a topic, only to find it on the test.

Karun contemplated me silently. “I could teach you,” he finally said, and I felt myself flush. Perhaps he didn’t mean more than his offer stated. But how could he not see what an intimate invitation this was to extend to an unmarried woman my age? Fortunately, a wave thundered down upon us to hide the redness of my face. I fell over backwards, felt the sea squeeze into my ears and nose, tasted salt at the back of my throat. For an instant I was completely submerged—sand swept into my sleeves and packed itself in my hair. How would I face my mother now? I wondered, imagining the men on the train ogling me in my waterlogged clothes.

The water cleared to reveal Karun’s face. The wave had knocked him over as well, his body covered mine. He tried to disentangle himself, but stumbled, and fell face forward into my chest. The tip of his nose plunged into my bosom, as if trying to sniff out some scent, dark and hidden, from deep between my breasts.

He sprang back up before I could react. “Sorry,” he stammered, staring pointedly away.

A volley of small waves whitened the water around our knees. He looked so perturbed, I wanted to soothe his hand in mine. “It was the tide. It’s too strong.” He nodded but did not turn. “Have you taught many people before how to swim?”

He raised his head and regarded me without speaking. Was he having second thoughts—could our physical contact have made him change his mind?

Perhaps Mumbadevi herself sent in the next wave to set things right. She didn’t topple me, not quite, just made me stagger and thrust my hand out blindly through the foam. She knew Karun would grab for it by instinct, hold on to it so I didn’t fall. Prudently, she withdrew this time, without forcing an embrace like in her clumsy previous attempt.

“The tide’s a lot less rough farther out,” he said, as I tried to wipe the salt water off my eyes. “They’re just ripples there—they only swell into waves as they near the shore.”

“It must be very deep.”

“The drop is quite gradual, actually. I can take you. You just have to hold on.”

Somewhere from the beach came the call of a man selling shaved ice. “Gola, gola,” he cried, “limbu, pineapple, ras-bhari.” I pictured the two of us sharing a raspberry gola, taking turns to suck the syrup from the ice. The line between Karun’s lips getting darker with each intake, the same intense crimson as mine. When the ice was gone and only the stick remained, I would press together our lips. Not to kiss, but to see how the curves fit, his crimson aligned against mine. For who was to say this wasn’t the match that really mattered, more than horoscopes and birth charts and palm lines? That the compatibility between two souls couldn’t be reduced to this question of geometry, of mathematics?

“We don’t have to go if you’re afraid.”

In truth, I was a little nervous of water, had been since my school swimming pool days. But the iceman was far away on shore, my experiment there would have to wait. “As long as you think it’s safe.”

“It is,” he said. Then he took my hand and started swimming backwards towards the horizon, pulling me along into the ocean, past the coconuts and the garlands, past the woman with the billowing sari and the children diving into the breakers, past the point I could hear the iceman’s call or touch sand with my feet, until the waves were shorn of their foamy manes and the sea swelled silently against our chins.

2

A SCUFFLE BREAKS OUT IN A CORNER OF THE BASEMENT. THE Khakis have accused a man of being Muslim, they proceed to beat him. I see a doctor swing his stethoscope above his head like a whip, two women in nurse’s uniforms wield umbrellas and try to elbow their way in. Even the woman next to me does her share, hurling insults at the victim across the room. “Son of a pig sisterfucker,” she says, and aims a stream of spit in the direction of the commotion.

Although aware of the city’s partition along religious lines, I’ve never witnessed the hatred fueled by this division firsthand. I now understand the advice my watchman tried to impress upon me so emphatically this morning: only the very brave or the very foolish venture into the wrong area of town anymore. Still, this is a hospital, I feel like shouting—even if it lies in a Hindu sector, does that mean the only treatment administered to Muslims is this kind of battering? Had we been at Masina hospital in Byculla, would I be the one meted out such violent medicine instead?

They claimed this could never happen. Bombay was too cosmopolitan, its population too diverse, its communities too interdependent to ever become another Beirut or Belfast. “Just think of the financial give-and-take alone,” my father would say. “Without everyone’s cooperation the economy would simply dry up.” He’d point to the language riots of the fifties, the communal campaigns of the sixties and seventies, the waves of bomb blasts since the early nineties that blew up hundreds as they sat in trains or buses or offices. “Bring on whatever havoc you will—the city will remain united even if the rest of the country splits apart.”

For a long time, he was right—even the Pakistani guerrilla attack in 2008 seemed to only increase the city’s cohesive resolve. “See these people holding hands?” he asked, at the candlelight vigil outside the still-smoking Taj Hotel. “They’re neither Hindus nor Muslims, but citizens of Bombay first.”

I try to summon that spirit of unity now as I listen to the screams of the man being pummeled. How could we have fallen so far so quickly? Especially when Mumbai was on the verge of becoming such a world-class metropolis? The dazzle and architectural chic of the Bandra-Worli Sea Link, the City of Devi campaign that would fast-track us to international fame—who could have predicted that the seeds of our doom lay therein? I try not to loop once more through the arc of events that’s led us to our ravaged state, try to tune out the muffled crunch of metal meeting bone through cloth and skin. I must become more hard-hearted for survival’s sake, learn to channel my mind back to the memory of more pleasant days.

MY MOTHER’S REACTION to the swimming lessons from Karun disappointed me. I had hoped for tantrums, for drama, perhaps even a curfew, like my parents tried to enforce on Uma when she first started spending evenings late with Anoop. “It looks like a pillowcase,” my mother declared upon seeing me in my high school swimsuit. “Can’t you get something that better shows off your figure?” I realized then how old thirty-one was, how dire my prospects must seem to her.

So that weekend, Uma helped me pick something suitably revealing from a boutique in Colaba. Its blue and white stripes stretched over my breasts to remind me of yacht sails, of beach umbrellas. I imagined emerging from the showers like a Danielle Steel vixen, the water trickling down my neck and beading on my bosom as I walked seductively towards Karun. But at the pool, my courage evaporated as soon as I left the locker room. I covered myself with my arms as best as I could and scurried across to the shallow end.

Karun stood against the swimming pool wall, his knees bent, so that the water lapped against his throat. Sunlight set his body ablaze, the tiles burned blue and bright all around him, ripples spread glittering towards and away from his chin. “Come in,” he said. “The temperature’s nice.” Although his gaze flickered over my swimsuit, he didn’t comment on my new nautically themed breasts.

As usual, our bodies hardly touched. Each time I thought they would, he managed to skirt contact without making it look like a purposeful move. Today, we worked on the dreaded amphibian kick—he demonstrated the entire sequence without even grazing my leg. Was it just shyness that kept us so chastely separated, or lack of interest on his part? Where was Mumbadevi to transport me back into his arms?

“You worry too much about sinking,” Karun announced. “Let’s try it with a life ring around your waist.”

For a while I paddled around like some hapless circus animal stuck into a prop for an aquatic trick. Finally, after slipping out for the fifth time, I voiced the obvious. “Don’t you think it would be better if you kept me afloat with your arms?”

He touched me then, setting his palms against my stomach, sparking off all the right chemicals in my brain. I sensed a delicacy in the way he handled me, as if, made of china, I might drop to the bottom of the pool and break. This decorum worried me—how distressing if the only outcome of these lessons turned out to be my learning to swim.

We walked over to the beach at Chowpatty afterwards. I’d waited in vain each evening for Karun to take my hand—he didn’t do so today, either. More than hand-holding, though, I felt the greatest longing towards the couples sharing snacks at the food stalls. Swimming left me ravenous, but it seemed too forward to suggest we split a bhel puri or dosa.

“Should we get something to eat?” Karun asked, and I almost swooned. I steered him to the vegetable sandwiches—the safest, I figured, given the staidness he projected. “I know from the picnic how much your family adores sandwiches,” he said. “But would you mind if we tried something spicier, like dosas?”

The dosas tasted so good with their fiery coconut chutney that we ordered a second round. I boldly suggested we finish with kulfi, even deciding on the flavors—mango and saffron. The kulfiwalla rolled the frozen metal cones deftly between his palms to loosen the ice cream inside. He unmolded them on the same leaf for us to share, the intimacy of which prospect made us both blush.

We strolled along the beach, scooping up bites of the kulfi from the leaf with our plastic spoons. Karun ate more of the saffron, leaving the mango for me, since it tasted better. “I haven’t had kulfi on the beach like this in ages, not since my college years in Bombay.” He shook his head when I asked him if he’d kept in touch with his friends from then. “They’ve all moved away—things never remain the same.”

Of course, I really wanted to ask him about girlfriends—here in Bombay, or back in Delhi, or even while growing up in Karnal. But I couldn’t formulate a subtle enough way to pose the question. In three days, I’d ferreted out almost no useful information—Uma and my mother were appalled at my lack of data mining skills. We talked about such neutral topics like his research in particle astrophysics (studying quark densities to understand the origins of the universe) and the reason I chose statistics (all those exotic-sounding curves, from Gaussian to gamma to chi, I sheepishly confessed, drew me in).

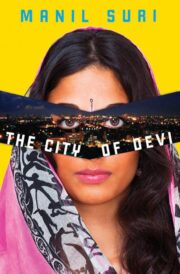

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.