No place for her in London, no place for her in Bath. No place for her with her aunt, with her father, her sisters. Arabella fought against a dragging sensation of despair. The wind whistled in her ears, doing its best to push her back down the hill up which she had so laboriously climbed.

Absurd to recall that just three months ago she had believed herself on the verge of being married, living every day in constant expectation of a proposal. It was a proposal that had come, but to Aunt Osborne, not to her.

A lucky escape, she told herself stoutly, struggling her way up the hill. He had proved himself a fortune hunter and a cad. Wasn’t she better off without such a husband as that? And she wasn’t entirely without resources, whatever the Musgraves of the world might believe. She had her own wits to see her through. Being a schoolmistress might not be what she had expected, and it certainly wasn’t the same as having a home of one’s own, but it would give her somewhere to go, something to do, a means of living without relying on the charity of her aunt. Or her new uncle.

Uncle Hayworth. It made her feel more than a little sick.

“She must not have been able to do without you,” said Jane.

Arabella wrenched her attention back to her friend. “Who?”

“Your aunt.” When Arabella continued to look at her blankly, Jane said, “You hadn’t heard?”

“Heard what?”

Jane shook her head. “I must have been mistaken. I heard your aunt was in Bath. A party came up from London. There’s to be an assembly and a frost fair.”

“No. I — ” Arabella bit her lip. “You probably weren’t mistaken. I’m sure she is in town.”

Captain Musgrave had expressed a desire to go to Bath. He had never been, he said. He had made serious noises about Roman ruins and less serious ones about restorative waters, making droll fun of the invalids in their Bath chairs sipping sulfurous tonics.

Jane looked at her with concerned eyes. “Wouldn’t she have called?”

“Aunt Osborne call at Westgate Buildings? The imagination rebels.” No matter that Arabella had lived under her roof for the larger part of her life; Aunt Osborne only recognized certain addresses. Pasting on a bright smile, Arabella resolutely changed the subject. “But Miss Climpson’s is within easy distance of Westgate Buildings. I’ll be near enough to visit on my half days.”

“If you have half days,” murmured Jane.

Arabella chose to ignore her. “Perhaps Margaret will like me better if she doesn’t have to share a bed with me.” She had meant it as a joke, but it came out flat. “I don’t want to be a burden on them.”

It was as close as she could come to mentioning the family finances, even to an old family friend.

Jane made a face. “But to teach...”

“How can you speak against teaching, with your own father a teacher?”

“He teaches from home, not a school,” Jane pointed out sagely. “It’s an entirely different proposition.”

“I certainly can’t teach from my home,” said Arabella tartly. “There’s scarcely room for us all as it is. Our lodgings are bursting at the seams. If we took in pupils, we would have to stow them in the kitchen dresser, or under the stove like kindling.”

Jane regarded her with frank amusement. “Under the stove? You don’t have much to do with kitchens in London, do you?”

“You sound like Margaret now.”

“That,” said Jane, “was unkind.”

Arabella brushed that aside. “If I ask nicely, perhaps Miss Climpson will agree to take Lavinia and Olivia on as day students.”

It was a bit late for Olivia, already sixteen, but would be a distinct advantage for Lavinia. Arabella, at least, had had the advantage of a good governess, courtesy of Aunt Osborne, and she knew her sisters felt the lack.

“It will not be what you are accustomed to,” Jane warned.

“I wasn’t accustomed to what I was accustomed to,” said Arabella. It was true. She had never felt really at home in society. She was too awkward, too shy, too tall.

“It is a pretty building, at least,” she said as they made their way along the Sydney Gardens. Miss Climpson’s Select Seminary for Young Ladies was situated on Sydney Place, not far from the Austens’ residence.

“On the outside,” said Jane. “You won’t be seeing much of the façade once you’re expected to spend your days within. You can change your mind, you know. Come stay with us for a few weeks instead. My mother and Cassandra would be delighted to have you.”

Arabella paused in front of the door of Miss Climpson’s seminary. It was painted a pristine white with an arched top. It certainly looked welcoming enough and not at all like the prison her friend painted it. She could be happy here, she told herself.

It was the sensible, responsible decision. She would be making some use of herself, freeing her family from the burden of keeping her.

It wasn’t just running away.

Arabella squared her shoulders. “Please give your mother and Cassandra my fondest regards,” she said, “and tell them I will see them at supper.”

“You are resolved, then?”

Resolved wasn’t quite the word Arabella would have chosen.

“At least in a school,” she said, as much to convince herself as her companion, “I should feel that I was doing something, something for the good both of my family and the young ladies in my charge. All those shining young faces, eager to learn...”

Jane cast her a sidelong glance. “It is painfully apparent that you never attended a young ladies’ academy.”

Chapter 2

They were everywhere.

Girls.

Young girls. Very young girls. Even younger girls. Not a surprising thing to be found in an all-girls’ school, but Mr. Reginald Fitzhugh, more commonly known to his friends and associates as Turnip, hadn’t quite thought through all the ramifications of placing nearly fifty young ladies — using the term “ladies” loosely — under one set of eaves. They thronged the foyer, playing tiddlywinks, nudging one another’s arms, whispering, giggling. There was no escaping them.

And someone had thought this was a good idea?

Turnip dodged out of the way of a flying tiddlywink, wondering why no one had warned of the hazards involved in paying calls on all-girls’ academies. Come to think of it, this must be why his parents had been so deuced eager to foist the job of delivering Sally’s Christmas hamper off on him. He might not be the brightest vegetable in the patch, but he knew a dodge when he saw one.

At the time, it had all been couched in the most sensible and flattering of terms. He was already planning to visit friends at Selwick Hall in early December; it would be only a short jaunt from there to Bath. It would give him an opportunity to test the mettle of his new matched bays, and besides, “Sally will be so delighted to see her favorite brother!”

Favorite brother, ha! He was her only brother. It didn’t take much school learning to count to one.

And where was Miss Sally? Some sign of sisterly devotion, that, thought Turnip darkly, leaving him stranded in a wilderness of young females armed with projectiles. If she wanted her ruddy Christmas hamper that badly, she could at least come to collect it.

He didn’t even see why she bally well needed a Christmas hamper. She would be home for Christmas. What was so devilish imperative that it couldn’t wait the three weeks until Sal hauled herself home for the holidays? She didn’t seem to be the only one, however. Among the bustle in the hallway were what appeared to be other siblings, parents, and guardians, bringing their guilt gifts of fruit, cake, and fripperies to their indulged offspring. The only one Turnip recognized was Lord Henry Innes, bruising rider to hounds, terror in the boxing ring, also lugging a large hamper.

According to his parents, there was a regular black market in Christmas hamper goods at Miss Climpson’s seminary and Sally didn’t like to be behind-hand in anything. It was, his mother explained, the female equivalent of debts of honor, and he wouldn’t want Sally to welsh on a debt of honor, would he now?

His mother, Turnip thought darkly, had neglected to mention the tiddlywinks.

“Mr. Fitzhugh?” A harried-looking young lady lightly touched his arm. From her age and the fact that she was tiddlywink-free, Turnip cunningly surmised that she must be a junior mistress rather than a pupil. On the other hand, one could never be too sure. Deuced devious, some of those young girls. After years of Sally, he should know. “You are Mr. Fitzhugh, are you not?”

“The last time I checked!” said Turnip cheerfully. “Not that names tend to change about on one that much, but one can never be too careful. Chap I knew went to bed one name last week and woke up another.”

Poor Ruddy Carstairs. He had gone about in a daze all day, completely unable to comprehend why everyone kept calling him Smooton. It had taken him all day to figure out it was because his uncle had stuck in his spoon and left him the title. It made Turnip very glad he didn’t have any uncles, or at least not ones with titles. He’d got rather used to being Mr. Fitzhugh. It suited him, like a well-tailored suit of clothes. He’d hate to have to get used to another.

“Ah, bon,” said the young lady, looking decidedly relieved, as well as more than a little bit French. Odd thing, nationality. She looked just like everyone else, but when she opened her mouth, the French just came out. “I would have recognized the resemblance anywhere. I am Mademoiselle de Fayette. I teach the French to your sister. Will you come with me?”

Turnip hefted the Christmas hamper. “Lead on!”

“Miss Fitzhugh waits for you in the blue parlor,” said the French mistress, leading him down a long corridor dotted with doors, through which various odd sounds could be heard. Someone appeared to be reciting poetry. Through another, rhythmic thumps could be heard.

“Dancing lessons,” the teacher explained.

It sounded more like something being pounded to death with a large club. Turnip feared for his feet when this new crop of debutantes was let loose on the ballrooms of London and Bath.

The French mistress opened another door, revealing a parlor that lived up to its title by the blue of its paper and drapes. There was, however, one slight problem. Or rather, three slight problems.

“I say,” said Turnip. “Only one of these is mine.”

The one that happened to be his jumped up out of her chair. There was no denying the family resemblance. Sally’s bright gold hair was considerably longer, of course, and she wore a white muslin dress rather than a — if Turnip said so himself — deuced fetching carnation-patterned waistcoat, but they had the same long-boned bodies and cameo-featured faces.

They were, thought Turnip without conceit, a very attractive family. As more than one would-be wit had said, they were all long on looks and short on brains.

It was only fair, really. One couldn’t expect to have everything.

Sally gave him a loud smack on the cheek.

“Silly Reggie!” she said, in the fond tone she used when other people were around. “I wanted Agnes and Lizzy to meet my favorite brother. It’s so lovely to see you. Do you have my hamper?”

“Right here,” said Turnip, brandishing it. “And jolly heavy it is, too. What do you have in here? Bricks?”

“What would I do with those?” demanded Sally in tones of sisterly scorn.

“Build something?” suggested one of her friends, revealing a dimple in one cheek. There were two of them, both attired in muslin dresses with blue sashes. The one who had spoken had bronzy curls and a decided look of mischief about her.

“Oh, Miss Climpson would adore that,” said Sally witheringly. Dropping the lid of the hamper, she belatedly remembered her manners. “Reggie, allow me to present you to Miss Agnes Wooliston” — the taller of the two girls curtsied — “and Miss Lizzy Reid.” Bronze curls bounced.

Sally beamed regally upon them both. “They are my particular friends.”

“What happened to Annabelle Anstrue and Catherine Carruthers?”

Sally’s tone turned glacial. “They are no longer my particular friends.”

Turnip gave up. Female friendships were a deuced sight harder to follow than international alliances.

“What did they do?” he asked jocularly. “Borrow your ribbons without asking?”

Sally set her chin in a way that her instructresses would have recognized all too well. “I liked those ribbons.”

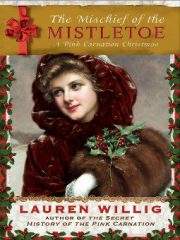

"The Mischief of the Mistletoe" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe" друзьям в соцсетях.