Wearing a new field gray tunic with a small SS eagle on the left sleeve, Adi arrived exactly on the second as he is never late because of the careful timing he learned from official appearances. He endured all the arms of the audience jutting up and returned their stiff salutes in his leisurely way—simply bending his elbow and raising his hand no higher than his right ear. Until he took his seat, everyone remained standing. Being invisible at the time—the lucky nobody—I was sitting in the back row. Magda pounced beside Adi in the prize position on his right. On the other side of Magda was Dr. Pfennig and Lilo. Much to Magda’s surprise, Lilo wore a stunning Schiaparelli topknot hat with soft feather trimming and a simple black and white herringbone suit looking beautifully unproletarian and very un-Nazi.

The doctor and Lilo were introduced to Adi, and the play began. A short burst of Wagner, and then the “turnip vet” was heard babbling. Adi leaned forward trying to understand the raving gibberish. Anguish echoed down stage when a captain without hands was flapping his arms in torment, screaming in a Bruennhilde-cry for morphine. Fortunately, most of the wounded were in a deep sedated sleep.

Deciding to act in his own drama, Josef delivered a monologue on hand-to-hand combat. Halfway through the oration, Adi leaned over and said to Magda: “The wounded look quite real.”

“They are, Mein Führer. For you, anything less than authentic would be profane.”

“How authentic?”

“From our SS hospitals,” she gushed.

Adi stood and the audience of more than a hundred military personnel stood as well—with Dr. Pfennig and Lilo also jumping to their feet. Lilo’s topknot hat towered in trembling attention.

“This is wonderful.” Walking briskly onto the stage, the Führer stepped in zigzag lines around the sedated and writhing wounded as Josef continued his monologue.

Then… it went terribly wrong.

“These are all vons,” the Führer yelled. And indeed they were. All were aristocratic officers who had impressed Magda. “Where are the noncoms?”

Josef stopped his oratory abruptly. Rushing to the Führer’s side, Magda looked at her authentic cast in horror. How could she have forgotten such a fundamental point?

“Here’s a private, at least.” A soldier with no ears and no arms who wore a pathetic paper surgery gown was one of Magda’s so-called “minor extras.” As Adi is able to stand aside and look at any situation in historical detachment, he observed this pathetic spectacle of a German warrior with no rank and no arms—a true common man—dressed in paper who saluted with his chin. “Decorate this soldier!”

“But Mein Führer… private Oels received his injuries in Bremen when he ran his jeep over his own gasoline can,” Dr. Pfennig said.

“A field decoration! Make him an Honorary Corporal in the German Army Reserves. Immediately.”

Huber Oels was grandly garnished.

Adi was then ushered to a large table of food set up on the summer porch. Taking a horrified look at the abundant and lavish dishes, he turned quickly and told Goebbels he could not allow himself to eat with his troops except when standing at a field kitchen.

The last time I saw Adi so angry is when that idiot American woman, Dorothy Thompson, wrote an offensive article about him saying Adi was “formless, almost faceless, a man whose countenance is a caricature, a man who seems cartilaginous, without bones.” Such words are untrue, sacrilegious and outright propaganda just like those ugly anti-Nazi White Rose pamphlets published by ignorant students who were later found and patriotically executed.

Adi transferred Dr. Pfennig to the Eastern front, a perfect revenge Magda felt for the doctor’s indifference towards her. Though Magda was treated coolly by the Führer for many months, she gradually got back into favor by personally cooking and serving him egg pudding, kasekuchen, and schokoladetortes that coated his throat in cream and left sugary rime on his moustache. She even made cookies in the shape of a special garland that Adi believed signified the eternity of the German world. As a last grand gesture, she took a patch of Blondi’s hair and wove it into a medal for Adi’s uniform explaining that the giving of this hair was a symbol that Blondi would trust him with her life.

Lilo and the children, we heard, rushed to a Stuttgart castle to be sheltered by an old couple still loyal to the Italian king—with Lilo’s do-gooder flashlight career over with.

As a salve to her ego, Magda took a U-boat officer as a lover. They would make love submerged during the day, repeating their ardor as the boat glided on the water’s surface at night. Captain Erwin von Kappe was famous for sinking 250 ships in the Eastern shipping lanes, and he wore the usual U-Boat uniform of khaki pants, suspenders, a gray sweater and a cap with large earflaps. When she asked me what I thought of him, I said: “He looks like a seal hunter.”

“Remember the silly birthday pageant, Magda? Are you over the good Doctor Pfennig? A doctor is hardly a prince,” I said with a taint of sarcasm.

“What made you think of him?” Living in the Black Splotch makes the past seem far away to Magda.

“And your rival Lilo?” I ask.

“That overly marzipan piglet is receding under the trough of failure. But… isn’t it better to think about your own love rather than mine?” Magda taunts.

“My love with Adi is sacred.” With a self-conscious smile, I cross my legs. With Magda around, I try to wear my only pair of nylons despite the runs patched over many times with natural fingernail polish. Thick gauzy clumps aggravate my ankles, and I end up having small red welts. But I refuse to care. I pretend they’re bites from Adi, little intense bites from that one-jagged tooth on the left side of his smile.

“I can stare at him for hours,” I coo. “I love the way he looks in his uniform. It’s no wonder that at the Paris World Fair in 1900, Austria won first prize for the most beautiful uniform on earth.”

“I’ve heard that story a hundred times.” Magda studies her palms in boredom, flexing her finger over and over, an exercise she believes will give her slender hands.

“He more than satisfies me,” I say.

“Oh, tell that to Blondi.” Her voice suddenly blares like a bus entering a tunnel.

“He does. Really, Magda.”

I don’t think Magda ever got too close to Adi. I do know she wants that more than anything. And maybe she has to play games with me like believing I can’t fulfill Adi as she could, pleasuring herself one way or the other even if it’s second hand. How can I blame her? I’m the one who has a poem that Adi wrote in small vertical old German script that he gave me after our second year together.

“I suspect his is beautiful,” Magda says begrudgingly.

“Why should it be beautiful?” I snap. “He’s the Führer. Isn’t that enough?”

“I know he has three testicles.” Magda stands defiantly, legs apart and hands behind her back, like one of her stubborn children.

“How do you know that?”

“Hess.” Magda says his name as if it were the ultimate source.

“Is that why Hess flew off landing in an enemy field? He wanted to make a peace deal with the British behind our backs because of one extra testicle? Our Führer is full of extras.”

“I never liked Hess, Eva. Right from the beginning. Even when he was the Führer’s respected deputy.”

“Tell that to Blondi.”

“Pfui, pfui. The Führer is always too trusting. You know that, Eva, trusting and… wonderful. Sometimes, when the Führer’s talking to us, when his passionate words are rolling from his jaws, sometimes…”

“What? Sometimes what?”

“His rear quivers. It makes you realize that somewhere in Europe there are psychics who can tell the future by one’s bottom.”

“Magda, I find that very offensive.”

“The marvelous slight ripples underneath his trousers…”

“You shouldn’t take notice of things like that.”

“Evie, for proof that we’re going to win, look at the rumps of our soldiers. They have rears more robust than before the war.”

“But Adi’s is mine alone. You can have the others.” I give an aggrieving sneer.

Adi used to lounge on the floor, his arms around his knees. With this great man sitting on the ground, I felt awkward resting on a comfortable chair. But his heart is always on the battlefield, down on the earth—close to the trenches. When he became the Führer, he leaned against his desk, and I envied the sharp wooden edges sinking into his skin. I’d look up his nose straight to his nostrils, unlike any other nostrils, for there were little dark hunks of tillage and clotted soil that he had coveted and conquered even there.

“You must remember, Magda, your Germany is gone. I’m the woman of the house down here. In the Bunker, I’m official.”

“Jawohl. Jawohl. You hope to climax at last.”

“And what does that mean?”

“Everybody knows the Führer can’t be bothered with sauce, even his own Sauce.” Magda pats her dress, the last Chanel that her husband seized when leaving Paris. The bodice is altered so that there’s a reverse cleavage with the ends of her pendulous breasts showing through an opening of silk just above her waist while the neckline reaches up around her ears. It’s a dress she continues to wear as a statement. Part of Paris still belongs to Germany.

9

AS THE IVANS GET CLOSER AND CLOSER, General Krebs decided that Magda and I go topside to do pistol practice. He feels every German man or woman is honor bound to take a random shot at the enemy, even me, as well as the Reichsminister’s Frau. The Red Army is in our streets, are they not? Americans are not far behind. Our pistol lessons would be a “surprise gift” for the Führer. And one had only to look outside and see ladies walking by with pistol belts over their pinafores for Goebbels decreed shooting instructions for women.

I’m elated for I yearn to go outside. Even though I love my home here below, now that I’m official, I want to ride in full view in the streets of Berlin. The thrill of it. Being seen.

Krebs insisted that Magda’s oldest daughter, Helga, eleven years old, also learn to shoot. At first Magda violently disagreed until General Krebs said his baby sister was shooting at the age of eight. Did the Reichsminister’s Frau want her daughter to be helpless? Maybe raped?

At eleven I had learned to handle a horse and throw a javelin, but I had no experience with a gun.

General Krebs and his orderly would drive to a suitable spot. It was not wise to shoot around the top of the Bunker and call attention to the Führer’s headquarters. Assuring us that Germany’s barricades and street sentries were all in place, he promised to do the driving himself. There are more of us in Berlin than the Russians. We would admit defeat by being afraid to go out in our own city. Furthermore, the general felt women should be prepared for their own safety, and the only way to do that was to be in the true and real arena up above. Finally, Krebs presented us with a large Walther pistol 7.65. To Helga, he gave a smaller Walther 6.35 and tied a little pink bow around her gun. Inside the barrel he stuffed schokoladecreme as Fräulein Manzialy struggles so successfully to save chocolate soufflé and chocolate karamelsauce in abundance for her Führer. Krebs chuckled and whispered to Helga that the Walther’s chambers were full, ready to explode and when she got an Ivan, she would see chocolate splatter on a Russian heart. Was that not a delicious way to end things?

“Won’t Uncle Führer be pleased when he finds we’re soldiers, too.” Magna was trying hard to be festive. “You know he says—everyone to their duty.”

Having experienced her first menstruation, Helga was pleased to be treated as an adult. Dr. Morell donated cotton from the tops of his medicine bottles to reinforce her underwear. When the cotton ran out, he pulled soiled bandages from the wounded that the nurses then washed and folded in little pads for her.

Helga was Adi’s favorite as well as her father’s. Both men wanted every detail about Helga’s first monthly that arrived according to Dr. Morell at a very early age, a natural sign of superiority. This young blood, her German heritage, Blut Träger, came forth in shy little bursts as if she had been pricked between the legs. We had prepared her for this monthly event, so Helga was not frightened. It helped that she was not afflicted with cramps. Adi insisted on inspecting the first bloody pad, so I wrapped it in the pages of my favorite magazine, Illustrierte Beobachter, and put it on his desk. He screamed at me saying the wrapping was contaminating Helga’s blood. Anything that was not Goebbels’ paper, Das Reich, was filthy. Disgusting print had bled on the cotton and distorted his examination. I had never thought of this possibility and was sorry telling Adi I would save him Helga’s second menstrual pad in the Panzerbär, the combat newspaper Goebbels so lovingly edits. But it was the first smear that he wanted. Finally he decided that the original sample was not ruined after all and wrote his name with her scarlet smear saying Nietzsche declared that those who wrote with blood would learn that blood was spirit.

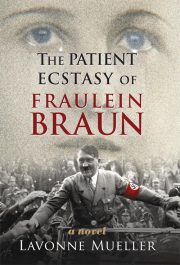

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.