Oberleutnant Bickisch began to stroke Helga’s hair tenderly where it lay spread out in Magda’s lap, his fingers lingering in strategic places. His hand disappeared underneath Magda’s blue skirt with the three pink bands near the hem. It was not well lighted, but I could see the glow on Magda’s face. Her eyes were bright, the same kind of brightness I saw in her daughter’s eyes when the child had a fever. It didn’t take long. It never did with Magda. She had all that perpetual foreshadowing from Goebbels. A slight upward movement of Helga’s head from her mother’s lap, and Magda sighed loudly, thumping her Schiaparelli topknot hat against the brick wall. Feathers drifted down into Helga’s hair.

“Sprechen Verboten” was printed all along the walls, but frenzied loutish sounds rose from the haze, the lustful shrill of the beginnings and the churr of those getting there. General Krebs was thrusting himself wildly inside Lola-Lola—right through her gauzy skirt. I hate passionate yelps. Adi will never let me cry out in such demented happiness. For me, it’s a very controlled whimper for he respects Joshua Reynolds paintings of restrained color and quiet strokes.

Oberleutnant Bickisch lifted little Helga up quickly, then gently put the sleeping girl in my arms. He blew out a candle near us and fell upon Magda. Moaning rose again. The French shoes in black suede and scarlet leather that Magda was so proud of were now locked around the neck of Oberleutnant Bickisch along with her rather plump legs. Helga was awakened by loud sighs, and I covered her innocent eyes with one hand. Helga kept taking my hand away. I put it back on her eyes. She pushed my hand away again. More shrieks of uncontrolled joy came from every corner of the shelter, cries scything into a heightened rhythm that crumpled in a surrender that almost screamed of death.

It was as if all this passion was the only way to defy the enemy. What better way to thumb your nose at the Russians? Let the Ivans fight in the streets. Down here the spirit of Germany could never be defeated. Yet, I did have some qualms. Didn’t they know a child was present? Could Helga recognize in the dimness her mother’s hefty legs? Magda should have had the decency to find another space far from her daughter or at least to have covered herself with a blanket. Feeling embarrassed for Helga, I also couldn’t help but feel an agonizing longing that I knew would linger for many hours.

We never had our pistol practice. On the way back to the Bunker, after vomiting twice, Helga splattered chocolate bullets at passing buildings, the steel of her pistol glowing in a soft bluish shine.

“The closer you get to the Bunker, the higher the rank,” Lieutenant Bickisch announced proudly, his one thigh tight against Magda’s leg.

“We’re going home. Wir fahren in die Heimat,” Magda said softly to her daughter with the roll of an ‘r’ as Adi does. (I was the only one in the car who knew “Wir fahren in die Heimat” was a line from the movie Menschen in Sturm, a famous film which starred her husband’s mistress.)

Lieutenant Bickisch adjusted a grenade on a loop of his black tightly buckled uniform. It was a “defensive grenade” that is used for protection if we had to quickly retreat, he told us. It would be thrown forward to shatter splinters and cause more turmoil than harm. “Don’t worry,” he said, “we will soon be in the splendid safety of the bunker.”

Speer said that the Bunker was sometimes a mask for people like Bickisch to hide behind.

When we returned, Adi was furious about his “surprise.” How dare the general take me, Magda, and precious Helga out in the streets where there were only vultures for the vultures to feed on. How dare the general make the Führer so upset and distract him from the war effort. It was treason, he bellowed in an Austrian accent that was impossible to conceal in his anger. I felt the vibration of his words run up and down my arms. Adi’s face was red, his mouth rigid over clenched teeth.

Snapping to attention, General Krebs clicked his heels, made a slight smart bow, stood at attention and referred to Goebbels’ orders to prepare women with pistol practice. And… did not Napoleon’s Josephine know how to shoot? “Much has been exaggerated about the destruction of Berlin. She still survives. She’s still resisting and alert. Do the enemy think we cannot traverse our own streets? I have brought you a film of many Russian prisoners who were just now captured in Berlin.” Krebs placed the camera on a table before Adi, bowed again but somewhat higher and continued to back his logic in and out of tunnels like the expert driver he was. “I’m in spirit an Austrian, Mein Führer. Nobody resents the awful loss of Austrian territory in South Tyrol after the First World War more than I. Such things make me daring for the cause and overly concerned about women. As you have always told us: Everyone to their task.”

Adi relaxed as his hands caressed the camera. This, indeed, was a tough general and no doubt his thinking was correct.

“Mein Führer, you will be glad to know that yesterday General Heinrici’s men captured and shot two American pilots after their planes went down just outside of Berlin.” He gave a shout and a stern salute.

Adi unexpectedly frowned. “Didn’t you read the classics at that fancy university you attended, General? Odysseus forbade his old nurse to rejoice over the death of the mendacious suitors saying, ‘old woman, rejoice in silence, restrain yourself, and don’t make any noise about it; it’s an unholy thing to vaunt over dead men.’”

“Of course, Mein Führer. One must respect any brave soldier.”

Later, Krebs confided to Goebbels that he had no idea if Josephine could shoot. He only knew that the Führer admired Napoleon’s empress as a woman who stuck by her husband and climbed with him to the highest position in the state. Napoleon made a mistake in casting her off.

10

THE PURPOSE OF THAT AFTERNOON WITH KREBS is important for I feel explosions from above rocking the Bunker. Like that one just now. I must learn any defense I can. Pieces of concrete are shifting and falling as the floor shudders. But I’d rather hear the whining of bombs because that means they’re not directly over us. Hearing nothing and feeling pressure in my ears means the bombs are close. And though other people are annoyed by “nuisance planes” which only fly over to scare us, I’d rather be kept awake all night with noise not bombs. When people complain about losing sleep, Goebbels calls their silly grumbling “the soul moving its bowels.”

What caliber guns are they’re firing at us? If Adi were beside me, he’d explain them as he lovingly did once by pointing to tracer beads in the sky as my own special string of pearls. 175 mm is heavy artillery whatever that is, but he assures me those shells won’t destroy a bunker over 30 feet under ground with 16 feet of concrete walls and ceiling. And we’re not under “army” concrete. It’s “speer” concrete, more trustworthy, Adi says. Since that July 20 assassination attempt, Adi’s no longer comfortable with anything but Speer’s construction—along with very select SS guards.

The assassination attempt was awful for Adi as well as for me though it had a glorious outcome. The villains were so sure of success that they took over the main radio station. But they didn’t succeed for long, and the radio was quickly taken back by the SS. I had some terrible moments when I heard the rumor of Adi’s death. I remember exactly what I was eating when a neighbor bounded into the room during dinner saying the Führer might be dead. My potato croquette fell automatically from my lips as if it, too, was shocked. But somehow I knew he was still alive as my heartbeat remained normal, my pulse calm. My body would have collapsed if He were no longer in existence. It would not have been possible for me to continue to breathe.

Goebbels said that when Adi was pulled from the wreckage, covered with dust and bleeding, the first thing he shouted was: “Send immediately for a salad of spinach and a spoonful of vinegar!” Diet was always his main concern for survival.

To assure people that he was alive, Adi gave a speech to the nation, his thrilling words spilling through their big wooden Siemens radio, splendid words spilling from the metallic threads of the radio’s fabric front. At one in the morning on July 21, he stated that criminally stupid officers had formed a plot to remove him. A bomb was planted by Colonel Count von Stauffenberg and exploded two meters away from him. Except for some minor bruises and burns, he was fine. This confirmation of Providence was the sign that he should continue his goal for the greatness of Germany.

Claus von Stauffenberg, his wife and four children were executed. Goebbels said it’s a very ancient custom that when a man is a traitor, his blood is bad, it contains treason and his entire family and remotest connections must be exterminated. I felt relieved knowing such evil people were gone.

11

WHEN I FIRST ARRIVED IN THE BUNKER, I called my mother every day. She’s in Munich with my sister, Gretl, who is pregnant. Shelling has become bad in Munich, even damaging the Excelsior Hotel. Mutti has her own chair in a nearby shelter and wears her platzkart on her sleeve to be allowed entrance. Desperate and down to a few cigarettes, she has to use them as money. Forced to sew one of father’s undershirts as the bodice of her dress, she also sleeps in a kitchen curtain. She has to wash in an old wine vat thirty years old when she can’t reach Cousin Gerda’s office to take a shower, hot water being available only in government buildings. She resorts to “black butchering” by having my cousin, Gottfried, kill a cow that’s not registered and has to cook it slowly and in small pieces on a spirit lamp full of eau-de-cologne. Even though she lives in the upper class neighborhood of Bogenhausen, Mutter says she’s one of the “snake women” who continually stands in snaking lines every day to get bread. When she lost all electricity, I sent her our Bunker candle stumps so she could remelt them. Even doing that is impossible now.

“Did not Adolf claim he would never make the same mistake as the Kaiser had in World War I by fighting on two fronts? He condemned two fronts in Mein Kampf. That much I’ve read. Now people say der Führer has declared war on us as well,” Mother writes. “Is this what our Messiah for the next two thousand years has given us?”

I have to remind Mother that America is fighting on two fronts, also. How can Roosevelt send enough ships to both the Pacific and the Atlantic? Her disrespectful prattle annoys me, and I insisted that she write me more patriotically.

I now rely on letters delivered by Adi’s officers as I can’t get through to Mother on the phone. Occasionally a runner or one of the generals brings me news. Mother is anxious for Adolf to work harder to bring about the solution to this war. “The poor Volk are being killed. Children in the streets are chewing their thumbs and fingers, biting out skin, cannibalizing themselves. Women eat the starch used for ironing. Your Aunt Irmela is called a “bombing wife” because she continues to live in the ruins that were once her home after the thousand-bomber attack on Cologne. And I’m using stalks of potatoes as writing paper.” Not that she doesn’t trust Adi. Like everybody else, she wants a quick solution and is panicky. Adi’s been very good to her. It would take pages to list the gifts he’s given her—flowers, silver, perfumed soap. And before the war, she would visit the beer hall where Adi had his putsch and got a bullet in his arm. She never passed that beer hall without tossing a flower at the door and whispering a tender “heil.” She used to make his favorite Schaumschnitten with two inches of whipped egg whites as well as cauliflower custard, and both were carefully packaged and promptly delivered by Adi’s private Ju 52 transport plane. But her last annoying message expressed dismay that Adi talks about the breeding of dogs at a time like this.

At dinner yesterday, as Adi drank his usual glass of Fachingen mineral water and banana milk, he told us it’s best for a female canine to breed two days after ovulation.

Josef Goebbels, who is certainly good at human breeding, slurped his red pepper soup while giving instructional glances to the orderly serving us. “How can you calculate that?”

“With patience,” Adi said, faint red trickles on his lips.

Magda, who always likes to impress the Führer, remarked that it’s best not to breed at the first heat.

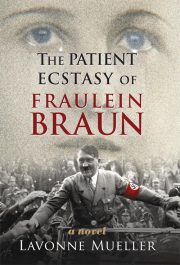

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.