“Rommel, that sly Swabian fox,” Hans bellows. “What’s this myth about him being a great general? He spent too much time sitting on his heels in camel thorns like a native and no time with his supply lines. He had his ears so close to the ground they were full of sand fleas. He didn’t know what was going on around him.”

“I rather like his ‘Panzer Song.’” Magda begins singing: “Panzer rollen in Afrika vor…”

“And he used planes. You don’t hear about that,” Hans states.

“I heard,” I say proudly. “He flew over the battlefields in a Storch light observation aircraft, landing around his tanks.”

“Who told you that?” Hans asks.

“Goebbels.” It was really Göring, but I don’t want to bring up Göring’s name at this time.

“Rommel was constantly in the front lines. We even bombed him a couple of time ourselves.”

“Didn’t he win the Blue Max?” Magda asks.

“Long before this war,” Hans says dismissively. “Africa was all a sport to him. Open terrain. No civilians. Sharpshooting into the vision slits of French tanks. A game.”

“I miss those wonderful boxes of Magenbrot he would send just to me… such delicious sweet Swabian cookies,” Magda gushes.

“But from the desert, Rommel learned that silence and loneliness are infinite,” I interject, repeating what General Keitel once told me, in order to counteract Magda’s remark about silly cookies. “Is that not valuable in wartime?”

“The real hero of the desert was the German 88 mm, the most effective field gun against tanks in Africa. Ladies, better to think only of hofmann,” Hans brays.

“Of course. Precious Hofmann,” Magda says.

Magda is more sad about Hofmann dying before she could get him in her arms than the fact that he had died so heroically.

Trying to put Magda’s ripped sleeve back where it belongs is an impossible gesture. But Hans tries, the back of his hand brushing across her breast. Though she has calmed from her war fury, she’s now agitated by lust.

“You must eat noodles,” I say to both of them. “A full stomach is comforting.”

They don’t hear me, see me, or know that I’m there. The room has become still. They stare at each other without moving. From the situation conference in the map room comes the faint chatter of Generals Krosigk, Keitel, and Ramcke along with Götz Rupp, Goebbels, and Bormann talking to their Führer. I see them all as the door has been flung wide open because Heinz Linge goes back and forth with trays of cups, tea, and platters of pflaumenkuchen, crullers, and egg pudding to pacify the raving sweet tooth of his Führer. The cakes smell of dampness. Adi doesn’t care, he happily nibbles and gestures with a cream puff, jabbing it into Bormann’s chest of medals and smearing yellow cream all along his top buttons.

“I absolutely oppose the machine gun because it makes close combat impossible. Jet propulsion is an obstacle to air combat. And developing an A-Bomb is so much Jewish pseudo-science,” Adi shouts. “Now a Panzer tank… that’s a superior weapon. One 25-ton Panzer IV has 39,000 kg of steel, 195 kg of copper, 238 kg of aluminum, 63 kg of lead, 66 kg of zinc, 116 kg of rubber.”

“How magnificent is your memory,” Krosigk proclaims, smiling. “You know everything about the Panzer down to its pistol ammunition.” I wonder if the rumor is true that the general still has all his original milk teeth.

“I also continue to read the railway timetable.” Adi begins reciting from memory complicated arrival and departure times.

How long will Hans and Magda stare at each other like two fascinated animals? Who will make the first move? I think about the insect world where sex results in death.

“There! Right there! A formation of tanks are crowded together,” Adi shouts, and he’s pointing to his detailed ground plans with black dots to show where mines are planted. “Can’t you see, Generals?” He says Generals and makes it sound like bums.

“Their white stars are clear to see,” Goebbels remarks.

Götz calls loudly for ordnung. Order! Gunfire suddenly erupts for Adi shoots into the concrete walls to establish himself in the real war. He does this exercise for Corporal Götz Rupp feels it’s important that Adi relive active battle. Corporal Rupp yells: “Grenade!” Adi holds a phantom grenade so real to him that his fingers move expertly to work the pin loose.

The generals back away from the action as Corporal Rupp tells them that warfare is determined by the quick thinking of the common soldier in battle. Animal instinct moves that soldier to decide whether to advance or whether to employ one form of artillery over another. It’s the unplanned, the spontaneous decisions that brings about historic consequences. Things get exciting only when things go wrong, Götz tells them. He gives an example: “Place a grenade on the helmet of a soldier. If the grenade is balanced, he can pull the pin and stand at attention. No damage if the soldier maintains absolute stillness as the explosion dissipates above his steel helmet. But if he becomes rattled and lets the grenade fall… you see, it’s all in the hands of the individual.”

General Keitel is enraged. “Are you saying we should not give orders?”

“You know the old saying: ‘Germans won’t fight without an order.’ However, we can’t rely only on generals. Not even the great German military,” Götz says.

“Can you please restate that in high German,” General Krosigk orders sarcastically.

“Come now,” Goebbels pleads, “we all wish to kill the same enemy.”

“I don’t consider the act of killing so difficult,” Ramcke adds. “One has only to pull the pin.” In his uniform pocket, Ramcke carries a tin of loose gold nuggets that he shuffles with his fingers like worry beads.

Corporal Rupp calmly leans his small frame against the wall near Adi and stares with coldness at General Keitel. “You read too many diplomatic correspondences, Herr General, such as all those papers detailing the glider assaults of the Witzig’s group. Nevertheless, your presence is necessary for the genius of inactivity.”

Moving close to Götz, General Ramcke mockingly whispers, “I tried to get you a cashmere bathrobe, Mein Führer.”

Götz ignores the malicious mockery.

General Keitel’s ears turn red and his jaw quivers. He murmurs unheard words in fury while flapping the field glasses around his neck.

“To have generals standing around does contribute to morale.” Corporal Rupp gives a half-smile, like Blondi’s half-wag, and his ropy lips hold the smirk for several minutes.

“Didn’t Wordsworth talk about wise passiveness?” adds Goebbels hoping to calm matters.

“You can quote an Anglo at a time like this?” General Ramcke shouts.

“Well, we’re fighting them, aren’t we?” Götz shouts.

“Rupp, your impertinence is outrageous,” Rancke slams back.

“Remember, General Ramcke, I’m not a Nazi. Strictly a soldier,” Götz declares.

Adi likes dissent. It’s what he calls expanding. It makes his officers accountable for what they plan. But he moves on to more important things. “Herr Rupp, as you know, I’m particularly interested in the concept of German instinct and its importance against whatever struggles befall us.”

“There’s only unreason in times of war, Mein Führer,” reports Götz. “My official statement on the matter. You can verify that in the SS Questionnaire of 1934 which I completed at the Brown House in Munich.”

“Doesn’t unreason have to be adequately reasoned?” asks Goebbels.

“Not if it’s spontaneous.” Corporal Rupp tosses written reports to the floor.

The generals scramble to pick up the scattered papers. All this heated bickering, Adi knows, is widening everyone’s thinking.

“Your official reports have nothing to do with what takes place on the front,” Corporal Götz Rupp says.

“Are you saying we lie?” General Ramcke screeches.

“Official reports contain meaningless details.” Corporal Rupp smashes a page on the floor with his foot. “The victor will be the country that no longer has any forms left. We have axed the Church, but we still honor Saint bureaucracy.”

“The front is getting thicker. Every day. We’ll be unable to even cover it with forms. 3,000 km and growing. Anywhere you look, it’s the front. Up. Down. Sideways. Length! Colossi!” As his nose swells wider, Ramcke could defeat Götz by sniffing him down.

“Generals. Let us calm down with a brandy. Courvoisier,” Goebbels blusters. “Mein Führer allows Courvoisier in his presence as it’s Napoleon’s favorite.”

The day the French armistice was signed, Adi spent one full hour at Napoleon’s Tomb in silent meditation. So of course they drink Courvoisier.

“It was wrong to put Napoleon’s Tomb down in a hole, Adi announces. “I wish to be placed high.”

“We must not think of such things regarding you, Mein Führer, our youthful, vigorous leader. Better to remember our Führer’s visit to the Paris Opera Building where you knew more about the architecture than the director and took over the guided tour yourself,” Keitel adds.

“Ah. The French occupation,” Ramcke sighs. “Those were the good days. We nailed the French that time… even getting our nasty hereditary enemy to sign the armistice in the very railroad car used for the surrender of imperial Germany on November 11, 1918.”

“And the glory of the Führer condemning General de Gaulle to death in absentia,” Goebbels offers proudly.

“It was the French military court who condemned him. They wanted Vichy to stay in control,” Götz corrects.

“It’s all the same,” Goebbels claims with arrogance.

“We conquered France for one reason,” Götz alleges. “To force England to be peaceful.”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Keitel shouts.

“Are we forgetting the elegance of our Führer in this whole matter? He—not any Frenchman—was the one who arranged for the remains of Napoleon’s son to be moved to Paris to rest beside his father,” Krosigk declares.

“That so-called son was only the emperor of France for two weeks,” Götz sneers.

“Corporal Rupp, I must remind you, it was a carefully planned gesture to have my name associated forever with Napoleon,” Adi adds calmly.

“No need to dwell on France. That’s in the past,” Goebbels states curtly.

Outside the map room, Hans’ beautiful hairy hand is reaching for a bowl on the table, taking a banana and stripping it until the curved firm pulp is exposed. He extends the tip to Magda and her fleshy white arm, looking like the plump rounded stem of a vase, reaches for it. Hans moves her arm away and places two fingers gently on her front teeth, lowers her head and purses her lips so she can only suck.

As Heinz Linge walks by, he sees both fixated on one banana, puts down his tray of tea and sweets, and seizes another banana under peaches and apples in the fruit bowl. His white service gloves are off gray and hard to keep clean from the Bunker dust. He holds out the banana, and Hans bats it away like some enemy artillery directed at his aircraft.

“The German people have proved unworthy,” Adi says. “I could have accomplished something even with a Weimar constitution if it were not for the traitors in our midst.”

“Yes, yes,” I hear Goebbels agree as his wife’s sucking is down one third of the banana. Der Chef Pilot rolls his eyes feverishly as his hand supports the disappearing soft curve. I feel a surge of delight. Banana dramas are hard to find in the Bunker.

“My Führer, more speeches and more parades, more postcards,” General Ramcke offers in a rasping voice. “But no more films like Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. She ignored the professional military. There were only quick glimpses of a few officers. She favors, of all things, the Labor service.”

Goebbels’ voice booms from the map room in a personal shrill grievance. “The Poles flouted the Corridor and went right on wandering down to the sea. They have the audacity to say you lied. Didn’t you straighten up the Eastern border?”

“You can print that in Das Reich. See that civilians get the paper free at least once a week. Announce it on the radio,” Adi orders.

“Introduced with a few soft drums. Then Beethoven,” Goebbels adds.

“The ‘fifth,’” Adi says.

I continue to scribble down their words hurriedly as Heinz Linge steps briskly out of the map room carrying an empty tray while Magda sucks down the remains of the banana’s flesh. With Hans’ eyes closed, Magda licks the heel of his hand for the finish. Then a child is heard crying, and Magda rushes off, the ugly screech of her chair on the concrete an abrupt indignity.

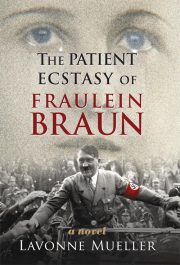

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.