As Helga puts her arms around Uncle Führer’s waist, he pats her hair. Taking a sugar cube from his pocket, he lifts Helga’s face, fondles her mouth, parts her lips lovingly to place a sugar cube on her tongue. Is he thinking of Geli?

“Sugar! Sugar! We want sugar,” chant the children, forgetting their humming, their waving fingers frantically clawing at Uncle Führer’s bulging pocket. As he hands out sugar cubes, he also gives one to Magda, Hans, and me. Loudly sucking, Hans speaks about a breakout as he rubs his Gold Wounded Badge (which he was awarded after five injuries) and flexes his chest so that his other medals jingle softly. He reminds me of a skilled piano player who never comes to the end of his keys, who leaves a vague hint of the final note.

“No talk of that in front of the children,” Adi says softly.

Magda hands the crying Heidi to Adi who cuddles the child gently saying: “Engelchen. Little angel. How well you cry.”

“Oh, my, oh, my,” says Hans to the children. “I’ve eaten the wrong end of my sugar cube first. To digest it, I have to get upside down.” He stands on his head and lets his legs slap loudly against the damp wall.

The children scream excitedly. Even Helga leaves Uncle Führer’s side to examine the rush of blood that turns Han’s face bright red. Adi moves the baby’s head to see Hans. Sitting on the floor, Magda smiles in glory as we adore and entertain her children. She uses them for her own vanity.

Adi used to play hopscotch with the children. One of his secretaries who visited New York taught him the game. When he found out hopscotch was once a religious game in which the final square is heaven, Adi forbade the children to ever play it again.

Once Adi was driven to a toy shop followed by scout cars and riflemen on motorcycles. He bought baby booties for Magda’s approaching delivery. Placing one bootie on each of his thumbs, he cooed to them much to the astonishment of the clerk. The next year he bought the children a rocking horse and when the tail was broken, he made one from his belt.

Adi leans down to little Helmut who has a constant running nose. “Now do you know what month it is?”

“April, Uncle Führer.”

“And what comes after April, Helmut?”

“May.”

“Very good. And what comes after May?”

“September, Uncle Führer.”

“Excellent. You’re a bright boy.” Adi straightens, then looks down with pleasure at Helmut’s curly blond hair.

“But Uncle Führer,” Helga says indignantly, “September does not come after May.”

“Helga, sometimes it does.”

Fräulein Manzialy trots in from the kitchen to ask her Führer if he wants the surprise now.

“Surprise! surprise!” the children scream. Falling gracefully to the floor, Hans is forgotten.

“Ja,” Adi says, handing the baby back to Magda. “Bring the surprise.”

As Adi goes to his bedroom, the children follow. But he closes his door on them, and they stand outside pounding and calling, “Uncle Führer. Uncle Führer.” After a few minutes, he opens the door dressed in lederhosen for he wants to be a common man especially with the little ones. Did not the Kaiser wear a gray uniform like an ordinary soldier?

Fräulein Manzialy rattles a saucepan for a dinner bell, then enters with a large glass of buttermilk for Adi, plum juice for the children, warm bread and a tray of corn on the cob, buttered and slippery.

“Corn on the cob. It’s wild food. The Red Skin natives of Canada eat it,” Adi tells us while adding three spoons of sugar to his buttermilk.

“But so do the Americans.” Magda is reluctant to touch a cob.

“Americans only eat from tin cans,” Helga corrects.

Adi forms a caricatured smile.

“It’s American Indians who eat it,” I add.

“We would do well to study such Indian skills of warfare.” Hans eats a slice of bread as he carefully eyes the corn. “I’ve researched how Americans killed their Indian inferiors. And how their plantation owners ghettoized black people.”

“American plantation owners? I’ve heard they were stupid,” Magda says.

“Plantation owners in antebellum South were known to conjugate Latin verbs.” Adi’s head is down isolating his face. A gentle man who wouldn’t even harm a dish, he moves his palm like a caress over the bowl and anyone seeing such a sweet gesture could not help but love corn.

“Latin has to be better than their awful American slang.” Looking intently at her corncob, Magda smiles.

“I hear their great hero, Frank Sinatra, didn’t weigh enough to make the draft, Mein Führer,” Hans offers.

“We have little to learn from Americans themselves.” Taking a napkin with faded beet marmalade stains, Adi puts it carefully by his plate. “The English are another matter. Their industrial leaders through the years have developed a superior base. And I am sorry that I have not managed to bring the English and German people together… though we started out with promise.”

“Didn’t Lloyd George give you a signed photograph of himself?” Hans asks.

“It read: ‘To Chancellor Hitler, in admiration of his courage, his determination and his leadership,’” I recite proudly.

Adi looks at me pleased.

Not to be outdone, Magda chirps: “Henry Ford admired you as well, Mein Führer.”

“Because I’ve always known that America’s outstanding achievement is technology.”

“Of course Ford was smart enough to be an anti-Semite,” Hans adds.

“Didn’t you once wish to make an alliance with America’s Ku Klux Klan?” Magda asks.

“The Klan was not political enough,” I tell her.

Helmut is making little soft balls of bread and using the crust to build a fort, his running nose snorting. The other children are restless and sip at their juice making loud smacking sounds. Helga looks at the Führer with adoration.

“I have no respect for U.S. troops. They like all the comforts of home at war. They’ve dishonored the influence of Baron von Steuben who was George Washington’s drillmaster. West Point used to have the spirit of von Steuben.” Adi finishes his buttermilk in one long gulp.

“I’m mostly interested in America’s Civil War, especially the details of Stonewall Jackson’s maneuvers in the Shenandoah Valley,” Hans says.

“Yes, yes. I have studied their Civil War.” Adi picks up a crust from Helmut’s bread-fort and chews it briskly.

“But look how idiotic they are now. FDR wants to drop thousand of bats over Tokyo to frighten the Japanese.” Hans hisses between his teeth in disgust.

“The bats died in transit.” Adi frowns for even an animal like a bat deserves respect.

“The Americans have so much space in their country, why do they want to come here?” I ask.

“A country never has enough space,” Hans answers.

“Anglo orchestras are not performing the great Wagner but play silly songs as… ‘Yes, We Have No Bananas.’” Magda begins singing in a throaty tone while looking knowingly at Hans.

“Nobody orders sauerkraut in the U.S.” I’m eager to show that I’m keeping up with the news. “And the Allies go around kicking dachshunds.”

Adi finds this hard to believe.

Picking up a cob, Hans asks, “You just bite at it, Mein Führer?”

“Do you have false teeth?”

“I’m twenty-eight, Mein Führer.” His face tenses in disbelief as he flexes his fingers anxiously.

Adi notices minor mannerisms in people. Looking at the pilot’s twitching hands he asks: “Are you impatient with me?”

“Oh, no, Mein Führer.”

“General Weidling can’t eat a corncob. Nubby bits of husk get under his upper plate. I had hoped he would give up meat as he has to use a spoon for every manner of eating. I try to keep his suffering in mind.”

“How unfortunate for Herr Weidling, a man so refined and appreciative of Wagner,” Magda says.

I report without thinking, “After his nephew’s plane went down, Göring was plagued with toothaches.”

“Toothaches? Even in a castle?” Magda asks slyly.

“He does like staying in medieval places. It was fun to visit him at Castle Veldenstein.”

“Göring is no longer my concern,” Adi interrupts without emotion.

Butter glows on the cobs as I realize I’ve said the wrong thing. How happy Magda must be.

“Those awful green elk-skin jerkins with leather yellow buttons that Göring wears. And his silly scarlet sword belt inlaid with gold.” Magda giggles. “He has more electric train sets than my children.”

“Not now,” I add. “Not since you only let the children take one toy with them.”

Magda’s face flushes in anger. “Something that awful Hermann would say.”

“Enough about Hermann Göring,” Adi snaps. “He’s not relevant.”

“Musical corn,” Hans says, chomping rhythmically and attempting to change the subject. He holds the cob respectfully.

“Corn and music are necessary opposites,” Adi says.

Adi puts a cob in each of the children’s hands, even the baby. Only able to suck the oil, the baby licks the grease as light yellow spit drips into runnels down her fat neck.

Two furry rats scurry along the wall, and I’m thankful Magda and the children can’t see them. To hear their infantile screams is aggravating.

Adi puts his teeth on the tender golden nubs to show the children how to eat it. They laugh, smearing the rare and hard-to-find creamy butter on their chins. Little wattles of yellow get wedged between their teeth. Helga looks like a squirrel munching and chewing. I smile. But Helga won’t be laughed at. Not since her monthlies began. She’s a woman. Throwing the cob down, she frowns at me. Adi puts his arm around Helga and lets her nibble from his own cob. Side by side, their lips move slowly along the yellow grist.

“Chew briskly,” Adi tells the children. “Chew manly. Teeth should chomp in d-major.” Taking exaggerated mouthfuls, I see his bleeding gums. As they make loud crunchy sounds, the children chuckle. He takes a napkin and with a magic touch folds it into a toy dog with jaws.

“You’re orchestrating the music of digestion. Make symphonies, my little ones.” His napkin-puppet slides the cob from Helga’s lips and tosses the yellow carcass on the table.

Helga hasn’t forgiven me for laughing at her. Sitting close to Adi, she refuses to glance in my direction. I don’t like her getting all Adi’s attention, not so close to my wedding day. I’ve been good to Helga, taking care of her when she got a sore throat last week, making a compress by stuffing oats in a wool stocking to lay on her throat, helping Fräulein Manzialy simmer soup for her like my mother used to make, hot milk with semolina. We added bits of horsemeat, but I would never tell Adi. Horses are very precious to him.

Magda triumphs in Helga’s hold on the Führer, placing the youngest on a blanket so they both can look up at him with admiration. Underneath her skirt, large thighs are folded in a hollow dip between her legs as she sits on the floor. It’s rumored that Dr. Morell enlarged her labium for she has the biggest crotch I’ve ever seen, and Hans’ eyes stare longingly at this hollow that Dr. Morell said was already so huge a baby could wiggle out feet first.

Magda also has rutty noises when she makes love, she confides, little belches due to her excessive vagina. Dr. Morell keeps her up to date with these medical side effects because of his research on the rabbits of Ravensbrück.

Göring tells me hundreds dip into Magda’s waters daily but not one has an idea. What does it matter when handsome men in heavy reindeer-skin coats gravitate to her? Long automatics in black leather sheaths send her into uncontrollable craving. Taught the pleasures of the body by hummingbirds, she imagines long spouts penetrating her flower.

Partial to our elite ski units, she reminds me that a ski trooper covers more ground in the winter than an infantry soldier in the summer. Magda likes men who cover large territories. Last winter, Captain Helwig Vielwerth came skiing to the Berghof wearing his sweater with a German Eagle and swastika on the front, an officer who uses adjutants to caddy his skis up the mountain. The first to greet him, Magda held out a mug of hot chocolate with whipped cream as she took the situation map from the Herr Captain that he’d been ordered to give Bormann. Soon Magda and Helwig were on the slopes together for hours, Magda using a pair of special white skis that her husband took from a shipment destined for our soldiers in Russia. She adored making love in the snow, but only when there wasn’t any wind chill. It was frigid enough without the howling gales and rustic enough being ravished by the swirl of careless white flaky snow. She didn’t like her eyes getting red rimmed from the cold, but it was worth it when she saw the captain trail-reading noiselessly for uncharted paths, his toe-binding making it easy to kick off his skis quickly as soon as he found a protected spot to lay her down. But keeping his skis on was her suggestion as that’s the way she liked it. Bending before her, he would crouch as before an inviting hill, and she’d open her long fur jacket so he could enter her vigorously—just as he would enter the pathless wilds. Helwig is an expert in terrain skills and knew all the ways of winding through a forest, moving through any woods as smoothly as in the open landscape. Her pubes would get little frozen skin patches, and he’d sweetly tap her frostbit mound to make a clinking sound… clink… clink… clink. This would inflame them with added desire, and they’d go on and on until his yank cramped and the slopes became dim from the setting sun. Magda was rewarded with hundreds of snow fleas jumping from one of her thighs to the other.

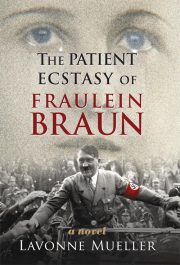

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.