“Where did you get the white mice?” I asked.

“Shipped direct from the old Knickerbocker Hotel off Times Square in New York.”

“Be serious.”

“Ratten hinaus! Donated by the science labs at Dachau where rats are kept.”

“Why Dachau?”

Goebbels has a policy of ignoring questions he doesn’t wish to answer. “I’ve always been careful with film. Enemies can easily hide there. I wrote to six American movie companies with offices in Berlin ordering an immediate dismissal of all Jews working for them—to stamp out that Friedrichstrasse crowd. I consider myself an advocate for natural culture.”

“Did you demand Proof of Descent from every film actress? Even the ones of a more personal interest?”

Again he ignores my question. “It’s always so pleasant to be with you, Eva.”

“I never congratulated you for getting an honorary doctorate from the University of Breslau.”

“I get many honorary doctorates, my dear.”

“Is that why you insist on people calling you Herr Doktor?”

“Doktor G will do, though pretty girls can continue with Josef, of course.” His look is outright jaunty.

“You know what some of your men call you?”

“Gobbespierre. After Robespierre.” He smiles. “Though I’d never admit it, I find that dashing.”

“They say you spend your time with literary chauffeurs.”

“Who is they?”

“Bormann.”

“What do you expect from an illiterate?” He suddenly looks down at his feet. “Eva, tell me honestly. Have you secretly despised me?” Running his fingers through his thin hair, he touches my arm to show that he now wishes to be more personal.

“Never,” I lie.

“Even a little? For not serving in World War I? For this tedious lament I carry around for the humble Russian soul? The very country that wants to eat us up. Do you hate me for being a cripple?”

“I never think of that.” But I do.

“I like a little bitterness with everything. I’ve been with women in Africa who have tattooed breasts. Some with two toes. Split feet are admired in many tribes.”

“How do you know that?”

“I’m the propaganda minister, am I not?”

I know that if Adi has only one man left, Josef will be the one.

“Let me show you.” Before I can demure, he unlaces his shoe, and I see the soft, pink deformed foot so sly and shifty it makes me think of that wobbly soft bunch inside his underwear. “Do you find it ugly?” he asks. He sees that I hesitate. “At what point do we declare something beautiful? Was all that scratching on cave walls deliberately made to be beautiful? You may prefer the normal or the regular, Evie, but Kant tells us that we instinctively look for form in whatever we behold. Even this. My foot is an aesthetic lesson.”

In between her lovers, Magda uses this “aesthetic” appendage often, claiming his deformity as a tool to pry her wider. That opening which issued six babies into the world hardly needs to be stretched.

Adi, who informs me repeatedly about the best and brightest future race, won’t acknowledge Goebbels’ deformed stem. “Look in any alley,” Adi says talking about everyday people who limp and lope through life, “good common Germans.” But must Goebbels be short as well? Is that why the Herr Doktor likes Russian literature so much? He can hide in the wide tall sweep of Russian characters.

“I was once temporarily impotent,” Goebbels confesses. “I went to a Buddhist temple and was told to have my penis bitten by a wasp. An old Buddhist custom. It did take care of the matter.”

“Was it painful?“

“On the contrary, though it did burst a blood vessel. But that’s all over with. Even my tapeworm is gone. Do you remember the party at the Sans Souci Hotel when I gave the Führer all those Donald Duck films?”

“But Josef, you told me yourself that silly Mr. Disney erased all the udders from cows in his cartoons.”

“He was quite right to do so. We must think of our children.”

“I would rather see films with real people. Real people don’t turn on their axis. Real people aren’t jumping mushrooms, spiderwood faces, purple cornflower horses, leaves with bloodless veins.”

“I adore fantasy, Eva. After all, I live in the country of the Brothers Grimm. I prefer the natural literature of the people, the Volkspoesie like the Grimms’ Kinder und Hausmärchen for the children. But remember, all those people in the Grimms’ tales acquired methods of thievery.”

“Only against monsters and witches.”

“Ah, then you do know the Grimms.”

“Adi loves fantasy and cartoons. So I have to be familiar with them. But those things are why he hates to dance, and I’m forced to waltz with doorknobs.”

“Das Lech is why he hates to dance, my dear.”

“I’d hold him so tightly not a drop of his essence would dare leak away.”

“Dancers are considered traitors.”

“Not unless they jitterbug.”

“Dance—and one forgets the war, Eva.”

“I would think it’s helpful to forget the war from time to time.”

“If it’s so helpful, waltz with me. Here. Now.” He gives off a forced Bohemian flair.

“There’s no music.”

“There’s imposed realism.” Goebbels takes my hand and begins to sing softly, “Es wird ein Wunder Geschehen.” It’s the popular inspirational song being sung these days… “A miracle will happen.”

“When will it happen?” I chant back.

“Miracles take time.”

17

SINCE ADI HATES TO DANCE, I see no reason to refuse Josef. We float around his office desk that is really a butcher-block table from the burnt out Rheingold Restaurant that once held dissected chickens and slippery ducks coated in oil. Now instead of hens, it holds cluttered requisitions for supplies that are nowhere to be found. I’m lighter on my feet than Magda, and he can move closer to me as my breasts are small, firm and resilient. He does lean against my orbs that become soft claws. Feeling a sense of modest revenge, I think of Magda and her little double, Helga, and beg him to tell me about his mistresses, all those actresses. He gave them up for a short while at the Führer’s insistence. But he couldn’t stay away from them, and Adi had to announce that a wife should not be annoyed over anyone as silly as an actress. If I were one, Goebbels might forget himself. But I’m Eva Braun.

“My actresses cry out in passion with a chaotic welter of so many voices and with such projection,” he brags. “Each has her own special nostrum.”

Josef wants to kiss me. It’s quite all right, we’re comrades, are we not? We love the same man. What is a simple moment in the eternal? He takes nothing from the Führer who never kisses.

Adi won’t kiss me on the mouth as he’s kissed no one on the mouth except his mother because the tongue can have a yellow coating indicating bacteria or cracks across the width revealing loss of nutrients—teeth marks along the edges mean bad digestion. My Adi can’t know what’s under the tongue, wet and hiding. As a boy, he saw a prostitute in Linz stooped in the shadows and shining a flashlight on her legs. Leering at him, she tried to get the few coins in his pocket that he thoughtlessly rattled as he walked. The prostitute then shined the light on her mouth and lifted her chunky tongue and he saw parasites there—tiny swarming parasites nesting in a cove of glistening pink. Two entire chapters of Mein Kampf are devoted to the evils of such women.

Josef says I’m silly to think he’d desire anything but the mouth beneath my nose. He simply wants me to kiss back and is patient. He uses his two bony fingers to purse my lips, then gives me a quick peck.

Afterward, my lips droop. Positioning his thin lips against mine again, he tries for a longer press. Different rhythms and pressures will sort out the superior ones. It’s scientific selection. When he sticks his thick tongue into my mouth, wiggling it, nearly gagging me, the great selector finds the perfection he’s after. “Schmeckt gut. Tastes so good,” he says. He ends with what he calls a Florentine Kiss. Napoleon invented it: Squeezing a partner’s ear lobes as his lips pucker on the woman. Why this is so Napoleonic, I can’t say. Pushing me against the wall, one hand on his groin, he projects a cry of passion like the actresses he so admires. Pulling away abruptly, and smoothing down his spent cull, he stares at me. I can read his mind. Never has he been so physically close to his Führer. Before he rushes off to the map room, he tells me, “The one thing I really miss, Eva, is my couch at home. A couch as deep as the one in Baudelaire’s poem.” Heading back to the map room, he softly whistles the miracle song.

Adi can’t tell I’ve been hastily kissed. Nor would he care. He’s immensely happy because he just had a night without dreams. Dreams disturb him. He sleeps so little, two or three hours. He’s afraid some errant thought will enter his subconscious and to avoid any invasion of his mind, he sleeps as little as possible.

Adi begins the day hopefully predicting there will be a rivalry between the Russians and Western Allies. That happens in a coalition. “Do you think the English will permit all Germany to go to Russia? They’ll fight among themselves, and we’ll be triumphant.” This is a device Adi uses, never settling into the moment but living in the days ahead. Projecting the future, he remains calm in the present. He tells me his prediction so I’ll enjoy eating the poppy seed strudel that Fräulein Manzialy baked with ingredients she’s saved over many weeks. He holds out a covered butter dish and instructs me to lift the lid. Underneath is a gift of a new toothbrush so hard to get these days in Berlin as even the big department stores are depleted. “Today, we broadcast on the Volksempfanger to our civilians that thousands of English soldiers in our prison camps will prefer to fight with us rather than fall into the savage hands of the Russians.” And I eat a second piece of strudel.

He holds out an iron that was given to him by Bormann. A Berlin woman was pressing the uniform of her son when she was killed. Her face was blasted off, but her arms remained ever ready, the iron clenched in mangled fingers. The good German housewife, careful to first take out the wrinkles in her son’s clothes before leaving the Reich forever. Now the iron is a monument as Adi puts it on a shelf next to the picture of his mother.

Nothing is without purpose. Adi tells me this over and over. You learn that when you paint. What if there was no oxygen? Oil painting would be impossible. Air is needed to harden the linseed oil. That’s the science of painting. The science of war is about little things like the air a mother breathes and a simple iron or a common domestic object like the bathtub. Napoleon’s crucial decisions were made in a tub where he always soaked his scabby skin.

Generals cause him the most pain, trying to get around his orders and making up maneuvers of their own. With the Russians practically on top of us, they expect Germany to surrender. This makes him furious and irritates his already spastic colon. Adi is fond of recalling the artist John Singer Sergeant who would dart behind a special screen in his studio in the middle of a portrait painting to vent his anger at the sitter—glaring and making faces from this sanctuary. Adi ordered Bormann to find him a “sargeant screen” so he could stick out his tongue and wag his fist at General Krebs, General Weidling and all the others. Bormann wrote up a screen requisition, but so far none has materialized.

It would have helped to have a screen to dash behind when dealing with Wallis Simpson. She and her husband first came to visit us at Berghof in 1937. The duke had told everybody that a war between England and Germany was out of the question, so we all rather liked him for that even though Adi hated skinny Wallis for what he called her “fake-countess insignia.” Ribbentrop, whom Adi let be ambassador to England, adored Wallis and constantly sent her flowers using party money. Adi put a stop to that, and Ribby had to bring her apfelstrudels that the Chancellery cook made for the Reich staff. Ribby didn’t believe in spending his own money on official matters.

What did the duke see in her? I’m amazed at the preference of men, particularly men in high places. They’re the ones most easily won over by simple flirtation. I know that from my own experience observing men in Munich. Goebbels enjoyed telling me that Napoleon was easily won over by the ladies. Apparently, the emperor’s clever way with military things left him more vulnerable in the bedroom. Not that Mein Führer is easily under the spell of women. Never. He’s always in control. Even when he’s out of control. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

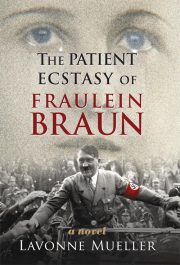

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.