Handing me a pansy, he’d say, “When I see a flower, my hand sees it first.” That’s how much he misses those painting days when he wouldn’t sketch people. He was right to concentrate on blossoms that could never betray him.

If we came across wildflowers he didn’t know, we’d give them names. I would start: “This is a Russian loser.” He’d add, “Rommelous Vainous.” And we’d laugh.

From painting, he learned about politics. The space around an object is there for the taking. Space. Untouched. Vulnerable. Brush in his hand, he could be anything. Paint couldn’t see him, but he could see paint. There was joy in sending one line running into the next—lines like soldiers, one depending on the other. He’d command strokes to look long when they were short, approach at one angle, then withdraw, make things brighter when they were dull. He moved trees from place to place. Those artist hands painted words even when he gave speeches, his gestures drawn so fully and colorfully. “Paintings are such splendid lies,” said this once poor artist who lived in an attic room on Schleissheimerstrasse.

Blondi’s bark would intercept any further thoughts on art. She’s always interrupting, something my two little Scotties never do. Smelling of dried urine, she oozes spittle on her jowls. She pivots in place like an idiot toy, turning around exactly seven times before lying down. Her mouth hangs open and her tongue droops to the side like a lecherous old prostitute. With a funny crate-nose, cold and wet, she also has wiry hair that makes her look bulky. She has chronic problems with irritated anal glands, a condition that gives off an awful oily smell. Because she’s always biting at imaginary insects like a horse chewing on its flank, the base of her tail is getting thin. Even when I divert her with a bone, she eats stones. Hot spots, areas of moist irritated skin, are on her back and hips—Adi calls them “Berghof sores” and treats them with iodine. Most irritating of all, she’s such a stupid pacifist she’ll sleep right next to a cow or cat if you let her.

The click of her toenails on the Bunker concrete drives me mad. She’s a poor sleeper and has nightmares, stomping her feet in her dreams. When they both emerge from Adi’s room, she half-wags her tail, a kind of salute that’s suppose to impress me. I’d be more impressed to see her tail out stiff and her body stuffed hanging on the wall next to Frederick the Great.

The three of us walk from room to room in this concrete—Blondi with her large tongue hanging out covered with dust. With Adi she neither snarls, snaps, whimpers nor splays her legs to spread ugly toes in a web when she walks as she does with me. Believing in sled dog rations, he feeds her fatty meat, forgiving a creature its inability to survive on vegetables. “That girl has stools that weigh almost two pounds,” he says triumphantly as I watch her squirm on the concrete rubbing worms out from her rear.

I dream about the old days—days above ground when the smell of dogs was not pungent. And that wonderful time Adi let me go to Berlin. Not to walk beside him. My visits were only “privately” official. I understood that. The fat housewives of Berlin know nothing about love outside their houses and chubby little brats. It was Goebbels who talked the Führer into including me, especially for that one great historic moment of cleansing German literature. “She can’t miss it,” Goebbels urged. Adi finally agreed, his consent influenced by the headaches I helped to lessen by rubbing warm oil on his forehead and placing liver slices over his eyes at night. Though grateful to me, he worried that a liver essence might have entered his retina.

He never insists that meat be verboten at his dinner table for a warrior who fights for Germany needs a belly full of bloody beef to attack. His generals eat like pigs. Adi reports to them, “Do we not have in common with Blondi a four-chambered heart? Don’t we both come from an egg? Don’t we both drink the same water?” Adi encourages women in every kitchen in Germany to mount a sign in runic script over the stove: “German Shepherds Divide Us from the French.”

At a staff meeting, he gave lessons to his officers who were fishermen on how to detach the hook without injuring the fish’s jaw so the creature could be released back into the water. He wanted no fish to be slaughtered.

That important day in Berlin, I carried a torch along with 30,000 students as we marched down Unter den Linden. Smart enough to tuck a pair of walking shoes in my bag, I wore them even though I desperately wanted to stroll in my laced black calf-high heels. This was fashionable Berlin. With sensible clogs, I’d be like a student. I’ve always looked young. Swimming and walking give me flawless skin. So I appeared quite youthful. With a wreath of heather on my head, I wore my full white dirndl skirt and blue sweater.

Before the main building of Berlin University, we sang patriotic songs as the SS threw books out the library windows and then dragged oxcarts of volumes like so many Joan of Arcs through the streets to be burned… 20,000 books to be incinerated not far from the statues of Alexander and Wilhelm Von Humboldt. A charming blond boy put a mangled book on Alexander’s stone head. How imaginative these young people were, how proud I was to be in their midst. If they only knew they were brushing up against the very woman who lives with their God.

In the square before the Opera House, “Gobbespierre” strolled proudly to the pyre. There was excited pushing and shoving but nothing out of control. For a small man, Goebbels’ hands are surprisingly broad and he angled them like a raft surfing through the thick slush of the common man. I couldn’t detect his limp. Maybe it was his posture or the handsome young men beside him in their SA plus-four knickers and brown shirts.

Goebbels likes to make important speeches at night when people aren’t quite so alert after a hard day’s work, when he can use blazing torchlights to whip them into a frenzied patriotism.

One student began to chant, “Optimus magister bonus liber.” Goebbels shouted along with him, “The best teacher is a good book. Get rid of slimy teachers.” I found it humorous that Josef Goebbels, who wrote a book that couldn’t get published, was now about to destroy all the published ones.

“Whenever I hear the word culture, I reach for my gun. Das Knaben Wunderhorn, old German folk songs that belong to our country, have no author’s name. That’s what we should honor.” Goebbels’ voice was shrill and pierced my ear like a stab. Nobody is more a lover of culture than Goebbels, but he was speaking for those who can’t handle words and ideas wisely, like people who can’t save money and are constantly in debt. Somebody has to make sure pennies as well as words are prudently parceled out.

“Better to turn a Nazi into a great artist than to turn a great artist into a Nazi,” Goebbels shouted. An open trailer rolled behind him carrying airplane wings marked with dark black crosses. There was cheering.

I felt the warmth of a young student pushing up against me. He wore an old postman’s jacket and began to rub his legs against mine, enjoying his own kind of camaraderie. He whispered his name in my ear: “Karl.”

“It’s necessary to execute devious books,” Karl told me. He had a high forehead and beady eyes without lashes.

“And the greatest book is Kampf.”

“You can hardly call that a book.” Karl’s hands, with the long tapering fingers of a good Aryan, were rubbing my back.

“Then what?” I asked indignantly.

“Experience. Didn’t all the medievalists turn from books to the earth itself? Like Copernicus—looking at the sun. The Führer’s book is the sun.”

I was happy I’d listened to Goebbels’ long-winded musings about Copernicus. “Ah, yes. The sun.”

“Like each of these.” Karl’s hands went under my sweater and squeezed my breasts as I leaned against his reedy chest.

“Do you mean—the life force?”

“The milk that is life’s knowledge,” he said. “A true Nietzsche thing unto itself.”

Göring explained to me that the Nietzchean Uberman was free from God. “To believe in nothing?” I asked proudly, showing off to Karl.

“To believe in prediction. Which comes from nothing. The Führer is at the center of experimental learning. He has used all technical application to predict the master race.” Karl took his hands away, and they hung long and lonely at his side.

“And just what laboratory is conducting these experiments for the Führer?” I asked shyly, knowing full well that unlike this young student, I could ask my question to the Führer himself.

“Ghettos.”

“Are you speaking of resettlement camps?” I asked.

“With a shaved head you can spot one instantly. Their skull gives them away. For science has provided the Führer a supreme view of the world. He’s dissecting inferiors for a brute understanding with the caveat of lösung. Solution.”

Karl’s thumbs moved to my armpit.

“Are they in discomfort?” I asked.

“Who?”

“The inferiors. Those being studied while resettled.” I was thinking of my mother’s Jewish cook who made cakes from a hand-printed recipe book when I came home from school as a child.

“Discomfort is subjective and cancels out a definition.” Karl’s ring began to rotate slowly in the moist hollow under my right arm. Then he giggled. “They say Freud has a phobia about riding trains; he calls it Reisefieber. He should stay in Germany. Our trains for his kind are short in duration. One way.”

“What do you mean?” My voice was weak. I was feeling slow radiating pleasure from my armpit.

“Jews have no political concerns. Our major objective is order. The Führer is the world authority. He knows what’s best for us, even what is best for the Jews and gypsies without any help from diplomats and their shabby compromises. He’s our mathematician.”

Grinding his ring in my underarm moss, Karl suddenly yanked his hand away pulling out hairs so that my skin smarted and a jolt of warmth traveled to the tips of my fingers. I was abruptly moved along by the crowd, and Karl was lost. As I stared at the volumes being torched, his words made me proud.

A student pointed to Erich Kastner who was watching his books burn. Nobody was attempting to harm a hair on his body, so why was Kastner so stricken? Was it because that silly Heinrich Heine once said that a country that burns books will burn people? How ridiculous.

Holding out a flask, a buxom girl with a pustular rash on her face offered it to me. I held it over my mouth and sipped dripping Scotch without touching my lips to the rim, then handed the flask to the young man next to me as I felt a searing warmth reach my stomach.

Goebbels lit the pyre. “Proust,” he yelled, and tossed him in.

“Proust,” screamed students who threw one Proust after another into the fire, the pages losing detail in the wrinkles and shrivels of darkening soot. Goebbels held up a bag of madeleines. “Filthy French pastry,” he yelled, opening the bag and tossing the soft cookies into the fire.

A schoolboy wearing leggings, a brown shirt and red armband with swastika grabbed a madeleine and stuffed the cake between his legs. “Let Proust taste this.”

Everyone cheered. A sickening sweet scent suddenly floated up. (I remembered those burning madeleines when I later smelled the strange scorched sweetness of decaying bodies in bombed streets.)

Leather and oilskin covers were burning in red gold smoke, the many authors Goebbels always bragged about knowing. I no longer had to be intimidated by any titles.

Opinions and arguments withered in flames smooth and silk as liquid. Where did words go? This splendid fire was on our side as it writhed with a strange life of eddies and swirls. Fire, that symbol of the sun, was now billowing and glowing in the spines of so many unhealthy writers. Streaks of raging blue-red grew higher. Pages began to stir—alert and twisting as though in glowing agony. Inferior sentences stood out—bulging from the page and resisting their fate with a miracle of sparks glinting from below. Blistering heat burst the ink bellies turning what was left of so many idiot thoughts into shiny white ash, the sturdy bindings left behind like flat hot skulls.

A housewife reached beside the flames to salvage thick half-burned covers for her cooking fire. Stokers punched the fire with long black poles adding fuel and holding up book-skeletons before slamming them down.

With his Kriegsverdienstkreuz Medal at his neck, Bormann looked on calmly. He already existed in a world without books and liked to quote Adi who said surviving these awful authors forever was a great deliverance.

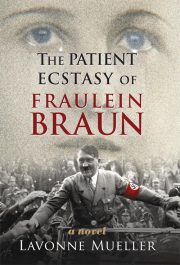

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.