“I need no equipment but my skin.” I stood proudly before him naked. “A suit creates drag in the water.”

“But you wear a cap.” He smiled. His teeth were better back then, less stress.

“My hair is not cooperative.”

“You mean your hair on top?” He wasn’t looking at my head. As I stood before him, I found it strange that he had no shadow, but I came to realize he allowed nothing to escape his body without permission.

“I do wear mittens,” I explained, “to make fists for good strong strokes, so I don’t over muscle the water.” Forcing myself to do physical things excited him.

His hand strayed between my legs, and he wondered what the ligaments of my clitoris were like—how firm they must be. Such ideal German ligaments deserved a strong man.

“I can’t do any freestyle with your hand there,” I teased.

“Then water-thrash.”

“You’ll have to take off your clothes, too,” I urged. The summer air lay heavily upon my shoulders. It would be months before I realized he took his clothes off for no one, not even his doctor.

On the collar of his tunic were the Iron Cross and the black ribbon of the wounded. Slung across gnarly branches on a tree above us was the Leica II camera that started it all.

“I like to dry swim. Fully dressed. Come now, create fluid motion for me. I’ve had enough today of the robotic action of politicians, my little Evchen.”

Taking his hand from my vee, he lay on the ground, face down and struck a perfect horizontal posture, his nose slightly slanted as he breathed to the side. Then he flutter kicked—small, fast and supple. Most beginners kick too big.

“I was gassed in the Kaiser’s War.” This he said without the slightest hint of pity. “I let air gently fall into my seared lungs when inhaling. I exhale through my mouth.”

“You’re so right,” I answered happily. “Weak swimmers tend to breathe only through their nose.”

Cupping the waves, he sucked on water from the deep darkness that most people fear.

I got on the grass next to him, and he moved me expertly onto his back as we both kept our bodies long, narrow and straight—he face down, me on the top. His tusk stiffened into the sand, and then I felt a slight arch.

“My pretty Evchen, we drink from the same bowl,” he said sweetly.

“Why don’t we do it the real way?” I asked.

“What way is that?”

“You enter my soil.”

“How much more real is that?”

Wanting another aperture, he reined me in digging into the crack of my bottom with his left hand (always saving his right for handshakes). After only moments, I think he was spent. One never knew with Adi. It took a while for me to learn that he stores passion like a special solitude, a sublime way of carrying the burning sun inside himself even as he writhes from his scorching juice.

I fell in love with his middle finger.

I’ve been on many beaches from the age of six. This particular shimmering swim let my body speed through swells and surges faster than any water I had ever know before. From that day, I knew I would always love him no matter what he did to me. For Adi carries magic even when he sleeps. He doesn’t snore, and there’s a soft glow about him when he’s unconscious as he breathes in little staccato puffs of air. I lie beside him thinking: “What is he dreaming? Who has taken him away from me into that other world?” It never leaves me, this fear of being left.

2

THERE WAS NOTHING IN MY CHILDHOOD that made me believe a famous man would want me. Oh, I had the usual dreams of marrying a prince like all young girls. In Bavaria, one heard of royalty and sometimes even saw them in parades. Pages from the Court of Wittelsbach, the Bavarian royal family, were sometimes enrolled in special classes at my school. Our priest, we were told repeatedly, was once a tutor to Prince Heinrich. But the nobility kept to themselves considering people like me as the bürgerliche—poor low life. Once I forgot and greeted one of the elite in the courtyard and was punished by the nuns with a rap on my knuckles. When I told Adi this, he smiled saying he ordered Heinz, his valet, to turn his back and bow when meeting a royal.

Prince von Hessen who survived World War I joined our Nazi Party. Prince Wilhelm became a member of the SS, and Prince Philip marched with the Storm Troopers every year at Nuremberg Party rallies. At first, Adi wanted the nobility in the Party in order to show a new people’s community—Volksgemeinschaft—the bringing together of all classes of society. But he was always suspicious of the Royals because their familes were international and thus a source of information for the enemy. Eventually Adi had most of those snobs thrown into prison for treason. Rommel, to his credit, put a good deal of blame of the World War I defeat on the aristocracy saying they used their privileges to no good end. But Adi was also suspicious of Rommel, a general who was arrogant enough to reprimand his students during their War College days that they need not concern themselves with a historical Clausewitz but with him.

My family is not stylish—just simple and honest. My mother, an ardent Catholic who displays her faith wearing a large red scapula, is a dressmaker who uses pillow feathers in her hat. My father is a teacher of crafts who has little interest in students and considerable interest in the principles of construction. As a child, my building blocks were discarded wood.

I was born on a rainy day and our roof leaked so the midwife delivered me wearing a rain hat and rubber boots. One hand came out first, and perhaps at that moment I was already reaching for Adi.

My sisters Ilse, Gretl, and I grew up in a small house with a wide yard, and we walked between rows of sunflowers taller than we were and went to a Catholic school and waited on the street corner to meet the nuns and carry their satchels. We were always told in our classes that we should be proud of Germany’s great art and literature. An deutschem Wesen soll die Welt genesen. The German spirit will heal the world. Any mention of imperial places like France or Spain would deform our character.

I was good in reading, poor in math, very athletic and was always chosen to be the leader of our exercises that we performed before church each morning.

So my life before Adi was very ordinary. But I wish those haughty Bavarian nobility could see me now.

3

THIS BUNKER IS MY FIRST REAL HOME. Like a ship, you’re born when you enter it. Here is my world of eighteen rooms where clammy air rises like part of the starkness of concrete.

Generals, officers, clerical staff acknowledge me. Before, I was hidden. Nobody was supposed to see me. Nobody was supposed to hear me. I was the secret woman.

In this Bunker, we’re staying put at last. In a sense, nesting. There’s bicycles sprawled along the floor and military furniture, horse blankets, field glasses, bull castration tongs, mess kits, tire rods, crowbars for me to contend with. I think of the Bunker as Michelangelo’s block of marble that can be turned into something wonderful even though Adi is against it. A bunker is a bunker. Probably it reflects his background as a corporal in World War I. Having seen conflict from the trenches, he’s down to earth. You don’t have to be born rich to get ahead. You can be a peasant and become a general at twenty-four and rule France at thirty. Little Bonaparte proved the common individual was able to triumph. I’m proud of Adi’s humble origins, but I worry, too, because now that the Allies have reached Berlin, they’ll shoot any corporal they find to make sure there’s never another Führer. Oh, I can’t let myself think about the bleak side of things. Not when ingredients for cakes are carefully saved in a tin box for Adi. They are modest cakes, but our cook, Fräulein Manzialy, who wears a swastika badge on her apron, has found just enough yogurt for icing. Adi’s favorite jellied pancakes are skillfully cooked in the shape of Napoleon’s hat. Yogurt is still unrationed and the beer supply is scarce even when it’s watered down though Adi never touches the stuff, and I only have a half bottle of schnapps now and then. Goebbels, our Propaganda Minister, found a raspberry liqueur that he and Magda drink each night before dinner with cakes in the Greek manner, and his First Adjutant, Lieutenant Wisch, (who wears the Medal of Blood from the beer hall putsch) brings them bottles of Juniper wine in hand painted bottles along with Eiercognac, and Samagonka (a Russian brandy made from beets). From Lieutenant Wisch (who is short and wiry and once was a jockey) we also get plenty of sugar and cheese. Lieutenant Wisch has five Opel Blitz trucks at his command and makes weekly runs to many of the big cities where he is liked by everyone and got to sign his name in the Golden Book of the city of Bonn even though he was born in Schuchten bei Treuberg.

Entering this stout old Bunker, Magda says, is like putting on a drab turtle’s shell. But after finding herself close to so many handsome soldiers, the turtle’s shell is more appealing. She moved a special end-table from her country home to the Bunker—a tiger-oak table with four naked men for legs, their genitals moving fuzzily into a complex of circles and cubes. When I complained it was unsightly, Magda huffed that furniture is the only way to “flower” the Bunker. When Adi accidentally toppled over this end-table breaking off a scrotum, Magda treasured it even more saying proudly to everyone that it was “broken by the Führer.”

I’m grateful for what we have in this damp shelter that groans and laughs depending on slurry bombs. There’s a little too much battleship gray and stark concrete for my taste. But many have less. Fräulein Manzialy never has the onions we crave for onions are used to make poison gas. But what can you do? It’s war. However, she mixes fried potato drippings to day old bread pudding, a succulent combination that leaves our lips moist and glistening.

Staying up late and watching for the first light used to be fun. Maybe it had rained and I could see blue lightning in the sky. Each morning I loved to watch Adi stand before his open window and do chest-expanding exercises that helped keep his right arm rigid for hours with the Nazi salute. But he’s given that up in the Bunker because he hardly salutes any more, and morning and night mean nothing. Every hour is like the last. That sameness leaves me time to realize how special it is to be here, how happy I am to finally be “visible.”

My first day in the Bunker, Adi didn’t come to my room that night as he was working straight through with Bormann, his adjutant, and Goebbels, his propaganda minister. He doesn’t go to bed until early in the morning and only sleeps a few hours, a habit he acquired as a messenger in the army. What little sleep he does get he fights as that awful thief of time. I was disappointed but too excited to be unhappy for long. My first night in our first home! Spreading an army blanket on the floor and leaving my pillow on the bed, I wanted to feel like a corporal on the front, one of Adi’s loyal soldiers. Wasn’t I at the nerve center of the most important command post in the world, in a place I was never allowed to be before, living among soldiers smelling of mud and sweat? Stretching long and straight on the blanket, I let my hands trail on the floor so I could feel the cold. I wouldn’t let myself go to sleep, even for a moment—not for the entire night. Shivering from intoxication, I whispered strange sounds, not out of fear but because of the restlessness you have in a new place. I didn’t use a blanket for I knew that would dull my bliss. I was throbbing with bursts of delight, as a shutter breathes on a window vibrating against the frame when there’s a delicious breeze. My eyes closed from time to time, content in the bowels of time, concrete around me like the Bunker’s own dream.

From the start, I keep my door slightly open during the day to hear life rushing by: gold-tasseled swords at a soldier’s side banging against stiff black boots, strutting captains, majors, and generals all working intimately with history. The bombs above slacken, then come hard rattling the lids on pots and pans, then slacken again. Sometimes a touchy guard at the top heaves a grenade outside the entrance at an imagined enemy. Life moves above, but this life swirling beside my room is a lofty heaven underneath. There’s no war, I decided that first night as I shook with rapture and anticipation, that’s too big or too destructive it can’t be held inside me.

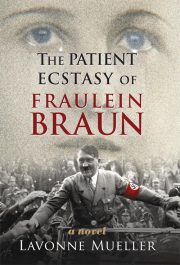

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.