The enemy, Adi assures me, have their terrible losses.

My Adi lies in bed, undressed and no longer timid about appearing naked, his mind still vivid and bright, that hidden masterpiece behind his forehead. Finally at rest, he’s Wagner lying on a sofa as Tristan, waiting beyond words or gestures or musical instruments in the helpless love for Isolde. I look down on Adi in the dark. As His body curls in a question mark, I place my hand on His head. For love of this man, I accept my fate. This is my gift, Vorsehung, providence. A little pillbox by the bed.

Yes, yes. I accept everything. I believe in His heart that includes all the bombs above and all the death and brokenness. I hold to His vision as those wildflowers at the Berghof hold to the earth. Without Him, I would die stupid.

“Louis IV said on the day he died, ‘Quand j’étais roi. When I was king.’”

“That was a silly Frenchman. You’re still the Führer. Now… say… I love you,” I urge.

“You know how I feel, my little soup-soul.”

“I want you to tell me.” I have a conjugal firmness in my voice.

“I married you didn’t I, sweet Evchen?”

He reaches for my arm, but I pull away. He lifts up on his side and looks down at me, surprised. Slowly he smiles. “I’m going to put you in for a decoration.”

But I don’t smile back.

Silence. Then he puts his fingers to his lips and moves them as he did Blondi’s lips when he wanted her to talk. “I… love… you.”

HE LOVES ME!

I do everything Magda says. Placing the worker’s cap over my hair, I sweat and rub the smell of Magda’s men between my legs, here in my Bierstuben, this smoky little cave just for him. I yodel, loud and clear, my mountain farmer’s voice of lushness and wildness that will define me.

All the following I have written so it lives forever on these pages:

My V-Volk is tossed against the wall now useless. He sniffs smelling Magda’s men and my worker’s sweat. His rutted beak, ruby red, striated, is bulging. With my factory hat still hiding my hair, I lean slowly over Him. Spending time with His fingers—he uses ALL of them (no longer needing to save his right ones for shaking hands)—he moistens his palms from the concrete walls to prepare my cleft, that tail of my heart, slithering in, sloughing. My blood increases by His probing. He expands, a slow steady slog, loamy, muzzy. He’s opening another map, this new road I have for Him, thrusting into a town, a field, a bridge. Swelling larger and larger, I think I’ll break. It’s dissection, being flayed, my earth frothing, abraiding. He’s my husband, guided by the heave of blood. Mein Gott. Ja! Ja! Everything begins to work inside, one strut after another in sickle movements, smooth ramparts of his hind part. His tip is Venice white, Munich cabbage pies slogging. Geli’s skin soaks me in formaldehyde. The smell of his mother’s illness. Blondi’s long canine uterus stretches me longer. Holding my organ in his hand, He divides skin flaps, frees up my ribs, strokes me, His giddy fingers deep, nicking away at my insulation, at my perfume of urine and stomach juices. I didn’t expect to feel so heavy, soaked with glorious connective tissues. He goes deeper into blood vessels more elegant than brocade, nerves and ducts like chiffon. I’m held within by the gravity of him as he loses his hands in my skin. Let it go, forget tender, forget. Ja… ja… ja… ja! Everywhere the back of His flinty tongue. Sehr beautiful. Ja. Sehr beautiful… ja… ja… osterblocken flowers roiled from His glans. Danka, danka… I love you, I love you I scream to my Adi who now lets me fill His eyes. My bulging under lips, faster… faster… shooting down stars in my satin purge. Me, opening his strength, racing to a gorge so glowing, phosphorous. I will shatter. Please shatter. I… am… splintering, light as spiders, breaching white peacocks, weedy, this Volkstrum agony. Nein, let me… nein, let me, let… me. Stilts of ecstasy as I bang, chug into myself, tearing apart the dark warmth of my brain.

We rise from the bed slowly, my body filled with soft ripples coming down from such exaltation. If we had time, I would press against him briefly. Being so charged, I could ignite us again. But this is selfish thinking. We have a stronger purpose, and he’s already begun to put on the common soldier’s uniform to place the Iron Cross on the left side of his tunic. He holds a picture of his mother tightly in his hand.

I put on the black dress with pink roses stitched near the neck, smooth the material down against my firm swimmer’s hips. I press a yellow tulip between my breasts.

He’s silent. It’s what Goebbels calls “Teutonic solemnity.” And I can only say Rilke’s words to comfort him:

Und wenn dich das Irdische vergass,

Zu dem stillen Erde sag: ich rinne.

Zu dem raschen Wasser sprich: Ich bin.

“And if the earth forgets us

tell the silent earth: I flow.

And to the rushing water say: I am.”

We arrange ourselves on Adi’s blue and white sofa where dots of blood linger from his piles. Soon more of his blood will crest the velvet. It’s early morning, but we only know that because of the small ticking clock on the table next to us. All the concrete blocks surrounding us seem closer than ever.

He’s brushing his hair with my “E.H.” brush, stroking so hard the bristles bend. When he holds the brush out to me, I drop it on the floor and calm down his hair with my hands.

Cyanide vials are held by his fingers so much shorter now. He’s withered wonderfully, thinned, relaxed. Wrinkles are gone from his face and he’s lost the unseen presence of conquest. Only his genius remains. He’s not what one will expect of a dead man. How beautiful will be the corpse of a man who doesn’t drink or smoke.

St. Perpetua, the strange saint we studied in school, was killed by a Roman pagan by guiding his sword to her throat. I put my hand on His and guide the capsule in his fingers to my lips.

We will die never knowing we are dead, side by side, a capsule soon on our tongues. We have only to bite down.

My notebook is on my lap, the pencil still in my hand. Adi is proud of me, proud that I’m happy to record each and every glorious moment till the end.

All I ever thought about down here, wished about, dreamed about was that I’d never be left behind. I hear the shells above. The Bunker shudders. The naked lights sway and flicker. Adi is beside me. When Bormann finally burns us, that trail of smoke we leave behind will be the “one long truth.”

I wish I could taste His ashes, my mouth pulpy with His power, destruction full of meaning, twilight of the Gods.

How much smoke will we make to taint the wind up above? Will my diary survive?

“Say something,” I implore Adi.

Holding his gun firmly, he’s silent.

“A genius always says something poetic on his deathbed.”

My husband leans the back of his head against the sofa carefully forming his words through the sifting dust. His lips slowly move.

“Mohnstrudel,” he says.

I know that nestled in our eternity, I will find this strudel for him no matter how hard it may be.

The shelter throbs and then moans in the seizure of a second tremor, the concrete gorging on us.

I will not let Him shoot the Führer. I take his gun. He doesn’t resist, and the sheer weight of the weapon reminds me I’m still alive. I lift the Walther 7.65 Caliber with my strong swimmer’s left hand, prop the barrel against His right temple while I hold tightly to my pen, ready to record every second to the end. The capsule on my tongue lightly touches my teeth.

Oh, history, you are mine now!

Pulling the trigger… I start to bite down as I… am… do… innnnnnnnnnnng…

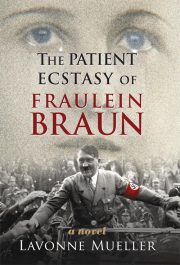

Reader’s Guide

with

Author’s Note

and

Discussion Questions

Author’s Note

This book does not pretend to be the history of Hitler and the Third Reich. I wish to give a portrait of a madman in the eyes of his mistress, Eva, who does not see him as mad. Her point of view allows us to go beyond the “crazy/sick” understanding that according to Primo Levi is almost to justify his actions. Henry Fielding in Joseph Andrews referred to his characters as “species,” something more than individuals and less than universal. That applies to my rendition of Hitler’s court.

We cannot indict only Hitler. His political sycophants were enamored and in awe of him as were many German citizens. Equally dangerous were the “common” men and women such as Eichmann, Hoss, Stangl, Magda Goebbels and Eva Braun.

It is tricky to write about a villain. Irwin Shaw attempted this in his novel The Young Lions, in which he portrays a psychological portrait of the Nazi soldier Christian Diestl. It would be easy to turn Diestl into a one-dimensional character. Yet Shaw makes him a tender lover and intellect, sensitive to black market dealings and the rough manners of his fellow soldiers. Yet Diestl accepts Nazism and the mass killing of Jews. Most critics believe that keeping Diestl from becoming only evil personified is the craft of true art.

Hitler is thus complex. Simplicity in marking the evil person—which Irwin Shaw avoided—would be a trap here as well. Hitler was capable of being brave, receiving the 2nd class Iron Cross in World War I, something rarely given to a corporal. He was a vegetarian who did not drink or smoke and was the first in advocating “no smoking” in a scientific move against cancer. He loved his mother, was thoughtful to his secretaries, always speaking to them kindly and bringing them chocolates. Yet… he masterminded machinery to kill men, women and children in a ruthless manner. There have always been wars, but none have ever included such organized assembly-line extermination, particularly of civilians.

I have taken Flaubert’s advice to keep a “singularity of vision” by placing Hitler in the primacy of Eva’s subjective reality. With my own imaginative interpretation, layered by archival documents, textbooks, memoirs, and news clips, I hope to render the intensity of a more complete vision to the reader in order that he or she may possibly learn from this operatic villainy.

I have been fortunate in being helped and inspired by such wonderful people as Barney Rosset, Howard Stein, and Glenn Young. And I have been enormously informed by historical information, mostly by the following books:

The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, William L. Shirer

Stalin, Simon Sebag Montefiore

Hitler’s Words, Gordon W. Prange

The Course of German History, A. P. Taylor

The Memoirs of Ernst Von Weizsaecke, Ernst Von Weizsaecke

Rommel—The Desert Fox, Desmond Young

War Diaries 1939–1945, Field Marshal Lord Abenbrooke

The Fall of Berlin 1945, Anthony Beevor

Strange Victory: Hitler’s Conquest of France, Ernest May

The Last Days of Hitler, Hugh Trevor-Roper

The Battle for Germany 1944–45, Max Hastings

Discussion Questions

1. What is it about Adolf Hitler that perpetually captures the public imagination decades after the end of World War II? What other historical figures from that period continue to be explored in popular books and movies today? When will the fascination with Hitler finally end? Will it ever?

2. What makes Lavonne Mueller’s novel different from other portrayals of Hitler in books, movies or documentaries?

3. Has Mueller’s approach changed your own perception of Hitler?

4. What effect does the claustrophobic setting in the bunker have on the action of the novel and the behavior of its characters?

5. How well does the old bromide “behind every great man is a woman” apply to Adolf and Eva?

6. Hitler, we are told, is married to Germany. How does this condition shape Eva’s destiny?

7. What if Hitler had won the war? How would a victorious Hitler deal with his realtionship with Eva? Would they ever have become man and wife?

8. How would you characterize their relationship? Is it similar to other relationships you know? Women sometimes feel they are in relationships with unbending monsters—dictators who control their every move. Or is Hitler forever in his own category of evil?

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.