Not even my mother influences me. Only Adi can tell me what to do. And that argument Magda and I had about wearing trousers! Being an athlete, I wear them often. Magda objects saying she can hardly let herself think of any woman in slacks strolling on streets or paths not even Marlene Dietrich before she became a traitor. As pants are better for getting around the hills at the Berghof, Adi says they’re practical. Even Goebbels said it was all right. But Magda is a prisoner of fashion—in the Black Splotch or up above. During the early war years, she wore outlandish shawl-jackets and coats with silver filigree and big brass buttons along with soft angora sweaters and dresses that emphasize her insinuating arms. But evening visits with various officers left telltale fuzzy angora signs on their uniforms, and she was forced to stick with clinging silk. And I have stayed with trousers at the Berghof.

Magda may think she’s the only one who knows all about social graces, but I taught the Führer how to eat an artichoke. We were at the Berghof when Fräulein Manzialy decided to provide the Führer with a little variety in his stable of vegetables. When she placed the artichoke before him, Adi gave a loud “Achtung! How am I supposed to eat this thing?”

I quickly took a fold, dipped it in butter, and put it in his mouth. He loved the taste and I began plucking each flap one by one and placing it between his lips. Soon he continued on his own so passionately that I became jealous. I wanted to be an artichoke. Later, he would devour the layers of an artichoke to the spirited chords of Die Meistersinger on a record that Marshal Italo Balbo, the much-decorated flier and Italian minister of aviation, gave him.

It’s strongly rumored that Magda was first married to an “aryanized” Jew she met at the smoky Sterneckerbrau Beer Tavern in Munich shortly after she had bedded a Hohenzollern prince for six months. Being so impressed with uniforms, she was instantly dazzled by this Jew’s field gray jacket with the bronze lion of the Freikorps Epp. Even at the beginning, he was different. He had a great deal of money and had to have sex three times a day. Just like food. And sometimes snacks. It wore her out though she got used to it and after a while enjoyed such frequent romps. Being a Jew, he had a mysterious way about him, so she plucked all her pubic hair and buffed her vulva to a high shine for him. He just put it in and took it out. He didn’t pump. Slowly… in. Slowly… out. Then he gushed, usually on the floor. So there was no dripping, no lingering drool, regular as their meals and teatime. If he was fully satisfied, she didn’t know. That was no concern of hers. He was a busy man making money. And she had no mess sticking to her thighs, no contraceptives to worry about. They did have a “possible” child, so the “drool” could have gotten in at least once. But nobody thinks her first child was from this Jew, however, as she’s had so many lovers.

This man, Magda tells me referring to her present husband, Josef, wants hours of what he calls foreshadowing. Hours. After his breakfast soup, he smears jam on her breasts, licking them off—two breasts along with two toasts and two coffees. In between meetings, he gallops to her room, dips a finger in her, a toe, a shoehorn, what does it matter. Later, it’s those dangly ears of his, thick and crude like sandpaper, propaganda ears meant only to hear what he wants. “I have to listen to his jealous tirade about Luther, the first real and only Minister of Propaganda whose theses posted on the door at Wittenberg spread around the country in 10 days. Think of it, Magda, he whines—10 days. What have I done in 10 days?” Finally, at bedtime, he jumps on her. This time there’s his cream clotting her carefully trimmed small hairs. Magda’s shiny painted lips are tense as she sneers. Who would have thought it possible that a Jew could please her more than a Reichsminister?

What’s it like to be rammed all the time, so finely tuned? Of course Goebbels is far from being the Führer. “Josef does that all the time?” I asked.

“All the damn time. And you?”

“With the Führer?”

“Eva, who else would I mean?”

Magda longs for Adi, sleeping at night with Mein Kampf between her legs and telling me how she dreams about licking his mustache. She tried to be with him all the time at official dinners before the Bunker days, when I was invisible and the lucky nobody. She would sit next to him in one of her shimmery beaded dresses with glass buttons, her one eyelid tinted pink and the other light green. Not known to the people of Germany, I was bad publicity. But Magda is the correct one who looks like a woman who gets her hair done more than anybody else and represents what is good in the German housewife. She was the official hostess, everywhere but at the Berghof. Even there she tried to win Adi’s attention, charm him, be clever for him… once holding up a stamp with his picture saying she was sending it to Roosevelt for his stamp collection.

When Goebbels said he respects his wife so much that he and his officers always get up and stand when Magda walks by, Göring once said in my ear: “She’d rather have those men lie down for her.”

For Adi’s birthday two years ago, Magda asked Josef to compose a pageant about the bravery of German soldiers. After it was written, she discovered the scenes took place on the battlefield. Magda cast the play using real war wounded from our hospitals to portray the heroic sick and dying in the script. Didn’t Riefenstahl select peasants from villages for her movies?

The Goebbels’ gardener from her summer home cleared the early April grass for a massive outdoor performance. At SS hospitals, Magda sought theatrical examples of suffering. Doctors objected to their patients being moved, even for a one evening performance. When she promised them an invitation to the pageant with a chance to meet the Führer, they usually gave way and even helped her find the most damaged men. She discovered an old blind vet of World War I who continuously hallucinated and raved all day from his bed about the Turnip Winter when his parents starved to death. Josef wrote a special Greek-like chorus for him.

Magda got distracted by the handsome doctors in their black and silver uniforms with twin serpents on the shoulders. Stopping by a florist shop on the Potsdammerplatz, she’d send mauve orchids to some of them. One in particular was Dr. Egon Pfennig who stated that he was in no way to be considered a putschist and was merely a simple doctor-soldier of Germany who knew what was going on in his country but didn’t understand it. From the old Swabian nobility, he once belonged to a student dueling fraternity at the University of Berlin and could list the scar on his neck as an identifying mark on his passport. She imagined his strong muscular back to be striped in craters deep enough for her long sculpted fingernails to travel down. Dr. Pfennig’s father was a Pour le Merite pilot of World War I, and he and his son wrote letters to each other in Latin, and she dreamed of Latin love letters.

Dr. Pfennig, handsome in a bloodstained rubber apron over his uniform, was cooperative in allowing his patients to be actors for the pageant although he did refuse to let them walk in a procession Goebbels proposed before the performance. Dr. Pfennig thought the drama might be helpful in the recovery process as so much research in medicine was discovering that the mind is capable of healing the body. What better way to be healed than to lie sprawled before their Führer?

Fearful of deserters from the front, Magda would brutally rip the bandages off the wounded when the doctors and nurses were not around in order to make sure she was not casting malingerers—even though each man displayed a wounded receipt with dates stamped and fastened to his chest. It created a lot of re-bandaging for the nurses.

But Dr. Pfennig had one curious fault. He was faithful to his wife, Lilo. Magda had never come across such a thing before.

There were attractive wounded to choose from. I would accompany Magda and Dr. Pfennig on audition tours. We found a captain with one arm and half a lung who insisted on wearing a regulation Foreign Office parade uniform designed by Ribbentrop instead of the hospital gown. Then there were the dreary young boys in drab brown Party uniforms who sat listlessly in the clinic halls flapping their empty sleeves to pass the time. Magda dismissed these with a regal smile. But she was excited about a colonel with one leg who was in the Sixth SS Panzer Army and had seized at least two bridges and one crossroad and complained that his only regret was not being able to march in the future victory parade through Brandenburg Gate. Another good choice was the major from the Africa Corps who had fought with Rommel and claimed cooking breakfast eggs with him on sizzling tanks’ tops. Dr. Pfenning, ever the scientist, said such eggs could only be fried with a blowtorch.

All her tricks were tried on the Herr Doktor Pfennig, but Magda only succeeded in getting him to kiss her hand. And that “kiss” did not linger. It was a snappy sullen sweep of his upper lip. With a soft lilting lisp, she’d say: “Doctor, are you not without a spare minute so we can be alone with these matters?”

“As you can see, I do most of the things here. Even the Kaiser’s son, Friedrich Wilhelm, with all his staff helping can’t find spare moments in these times of war,” the doctor answered.

“You’re mistaken. Friedrich Wilhelm viewed my newly acquired Rembrandt, Man in a Golden Helmet. And we were quite alone.” The pouches under Magda’s eyes pulsed with hidden secrets.

When the play was finally cast, with over one hundred wounded to be carted by ambulances to the Goebbels’ summer estate, Magda was nearly an invalid herself so much was she suffering with longing for Dr. Pfennig. Who was this Lilo who had such a hold on him?

Having had a dull Weimar Republic upbringing, Lilo was taught by dubious Jewish teachers and probably even Jewish professors at the University of Würzburg, all of them with Anglophile tendencies. She had studied medicine herself, but gave it up when her first child was born. Tall and thin, she had no thighs to speak of and when the war started, she volunteered to operate the searchlights that spotted Allied planes in the night sky. When Magda asked Josef if this was an important duty, he only laughed saying: “The English fly way too high for any little girl’s flashlight.”

“Then why does the Führer bother giving such assignments?” Magda asked.

“The Führer refuses to draft women. In a spirit of bonhomie, he threw them a crumb. The rise of Germany is a male event. It’s not that we don’t respect women. We respect them too much to contaminate them in battle. In World War I, we shelled Paris from 70 miles away with huge guns called Big Bertha after Krupp’s wife. That’s the kind of respect I’m talking about.”

So this silly Lilo Flakwaffen-Helferin was some kind of heroine to her husband. Magda made sure that Josef’s remark reached the doctor’s ear.

On the night of the pageant, Josef ordered many torches to burn on the grounds of their estate. Hindenburg lanterns were placed in the trees to illuminate the stage. Swastika wreaths were spread in front of the grassy stage where chairs were set up in long even rows. Josef decided to call his masterpiece Turnip Winter, as the old “turnip vet” seemed to him a prime protagonist. Though Magda wore a very narrow skirt and a corselette waistband that pushed up her breasts, I was dressed simply in a pale blue suit with a white collar and pocket flaps of cotton gingham. While my hair was styled more natural and fell softly around my face, Magda’s was swept up in an oversized platter.

Ambulances arrived, and the wounded were placed on various black markers on the stage of grass. Magda had ordered dozens of white scarves for the actors feeling bare necks were inelegant. Cries of pain were heard which annoyed Josef who wanted “pain” only on cue. Bandages on arms and legs leaked ringlets of blood on the ground. Two soldiers held out both arms held rigid in plaster. The doctors called these patients “stukas” because their arms looked like the wings of a Stuka dive-bomber. Josef was delighted with the “stukas” who saluted him in the official way of the armless—by leaning back their heads with their chins held high.

Musicians were ordered to warm up loudly in order to drown out the incidental groaning noise.

Attempting to demonstrate a showy mercy, Magda put a cup of water to a soldier’s lips though Dr. Pfennig advised her not to as the man had been shot in the lungs and water would drown him. Magna was determined. The man drank from her cup and died, and his body was hurriedly carted away, his white scarf fluttering behind.

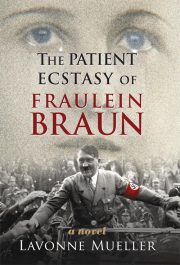

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.