“Treachery,” repeated Amy shrilly, “is when an unscrupulous man deceives innocent young ladies into believing he is a—a person of sense and sensibility! When all the while—”

“Innocent?” roared Richard. “Innocent? You’re the one who’s always picking fights with me! You call yourself innocent? I was innocently discussing Egyptology this afternoon, when you hauled off and started abusing my character!”

“That might be because you’re the one in the employ of Bonaparte!”

“At least I don’t go about throwing stones at other people’s glass houses!”

“Oh no, you’d just guillotine them, wouldn’t you?”

Richard grabbed Amy by the shoulders. “You”—shake—“are absolutely”—shake—shake—“ABSURD!”

Amy stamped her foot. Hard. On Richard’s.

“That’s for calling me absurd!”

“Owwwww!” Richard released Amy somewhat more abruptly than he would have liked. How could one small foot pack such a punch? He’d been attacked by grown men who hadn’t managed to cause him quite so much pain.

Amy backed away from him, visibly seething. “Don’t touch me; don’t talk to me; don’t follow me,” she spat, stalking towards the stairs. “I’m going to bed!”

“That’s the first sensible thing you’ve said all evening!” Richard snapped, hobbling after her.

Amy whirled on one—as Richard now knew—very dangerous little heel. Richard flinched, an involuntary movement that brought a flicker of malicious pleasure to Amy’s blue eyes. It might have just been a stray glimmer of moonlight, but Richard and his aching instep were pretty sure it was malice.

“I thought I told you not to follow me!”

“Do you expect me to sleep on the deck?” Richard inquired acidly.

Amy muttered something unintelligible, and started down the short flight of stairs.

Richard poked her in the shoulder blades, just below her tangled dark curls, which jerked satisfyingly in response. “What was that you said?” he asked.

Amy’s hands clenched into fists at her sides as she kept walking. “I said I’m not speaking to you!”

“Oh, that’s logical,” drawled Richard.

Amy emitted an inarticulate noise of great emotion.

“I say, that doesn’t count as speaking, does it?”

One hand on the door of the cabin, Amy gave an agitated hop that looked like it wanted to be a temper tantrum when it grew up. “Just leave me alone!” she whispered fiercely, yanking open the door. “Stay on your side of the room, and leave me alone!”

“Your wish is my command.” Richard bowed mockingly and disappeared without a sound behind the wall of cloaks.

Amy flounced over to her side of the partition, promptly tripped over the same portmanteau of Miss Gwen’s that she had whacked into earlier, and experienced no difficulty in convincing herself that it was all Lord Richard’s fault. Amy hopped into her berth, nursing her wounded toes. She had no doubt that, in some roundabout way, the storm that had stranded them on this dratted boat was Lord Richard’s fault, too. Most likely some minor deity he had offended getting back at him.

“I hate him, I hate him, I hate him,” Amy muttered as she drifted into sleep.

Within moments, Amy found herself on a balcony outside a ballroom. Through the open French doors came the sound of laughter and music. The candlelight traced intriguing patterns at Amy’s feet, but they failed to hold Amy’s attention.

She was looking over a garden—a large, elaborate, formal garden, with bowers of roses, a false classical temple on a distant hill, and a large, surprisingly unruly hedge-maze smack in the middle of the patterned paths and beds of flowers. And that’s when she saw him. Practically a shadow himself in a dark, hooded cloak, he slipped out of the maze and swung over the edge of her balcony. Amy reached out an eager hand to help haul him over.

“I knew you’d come!” Through the kid of his glove, she could feel the signet ring on his hand, a signet ring that bore a small, purple flower.

“How could I stay away?” he murmured.

Amy clung to his hand. “I so badly want to help you! It’s all I’ve ever wanted! Won’t you tell me who you are?”

The Purple Gentian ran one gloved finger down her cheek in a way that made Amy shiver with delight. “Why don’t I show you?”

Usually, at this point in the dream—because Amy had dreamed this same dream, not once, but several dozen times, down to the very colors of the flowers in the garden—Amy woke up, anxious, bereft, and more eager than ever to track the real Gentian down to his lair.

But tonight she watched with quivering anticipation as the Gentian painstakingly undid the knot holding his cloak at his throat, as he slowly pushed back the enveloping hood to reveal a head that glinted gold in the candlelight and a pair of shrewd and mocking green eyes.

“I’ll wager you didn’t expect to see me,” drawled Lord Richard Selwick.

Amy woke with a gasp of horror.

“Drat him!” You would think the nasty cad could at least leave her to dream in peace! Amy punched the pillow, rolled over, and went back to sleep. Lord Richard invaded her slumbers once more, but this time Amy didn’t mind. She dreamed with great satisfaction of pushing Lord Richard off the side of the boat, and then sticking out her tongue at him as he thrashed in the cold waters of the Channel.

On the other side of the cabin, Richard’s slumbers were equally uneasy—even though he had no idea that Amy was mentally chucking him into the Channel. He had lain awake for some time, alternately fuming over his own behavior and that of Amy. He had dismissed a ridiculous voice in his head (which sounded unsettlingly like Henrietta’s) that rather caustically informed him that if he wanted Amy’s attention behaving like a seven-year-old was not the best way to go about it. “She started it,” Richard grumbled, and then felt even worse, because, devil take it, he had sunk to the level of arguing with people who weren’t even there. If he continued like this, he’d be more fit for Bedlam than espionage.

Richard fell asleep while mentally drafting an instructional pamphlet for the War Office entitled Some Thoughts on the Necessity of the Avoidance of the Opposite Sex While Engaged in Espionage: A Practical Guide. The title itself took him some effort to get just right. By the time he finished composing Item One (“Under no circumstances allow yourself to be drawn into conversation, no matter how well read the young lady in question, or how fine her eyes”), Richard slid seamlessly into a familiar nightmare.

He was just outside Paris, making his way through the Bois de Vincennes to the rendezvous with Andrew, Tony, and the Marquis de Sommelier. Percy was to meet them at Calais with his yacht and the Comte and Comtesse de St. Antoine. Another successful week’s work for the League of the Scarlet Pimpernel.

Richard wasn’t feeling particularly buoyed with success; he was still brooding over that last call on Deirdre. She had been arranging flowers from Baron Jerard when he had arrived. Baron Jerard! What sort of rival was that! Forty if he was a day! Richard would be willing to wager the man couldn’t sit the back of a horse for the duration of a hunt, much less pull off dashing rescues with half the military might of revolutionary France in pursuit. It had been the way Deirdre said his name when Richard asked about the flowers that had set Richard off. “Baron Jerard called,” she’d said, and there was just a hint of something secret, something almost smug, only his Deirdre, his perfect, beautiful Deirdre would never possibly be smug. That’s when Richard rashly spilled his secret.

But when he’d told her . . . well, what he wasn’t supposed to tell her, she’d just kept on arranging Jerard’s pestilential flowers, and trilled, “La, you are droll, my lord!”

“What will it take to convince you, the head of a Frenchman on a platter?” Richard had cried in anguish, and stormed from the parlor.

Geoff poked Richard in the ribs. “Richard, something’s not right.”

Blinking, Richard realized they were already at the small shack they used for their rendezvous. And Geoff was right—something was quite, quite wrong. There should have been a scrap of scarlet cloth in one of the rough rectangles that passed for windows. The door of the shack hung ominously ajar.

The two old friends exchanged a long look, and crept silently along the side of the shack. “Ready?” Richard breathed. Geoff nodded, and they exploded into the hovel. Only to find one man lying twisted on the floor, his clothes dark and wet with his own blood.

Tony.

And then Geoff uttered the words that Richard couldn’t erase from his brain, not with a hundred bottles of port. “Someone must have tipped them off.”

“Damn her!” Richard cursed, as he thrashed in his sleep. “Damn her!”

Chapter Eight

Voices in the foyer jolted me out of Amy’s world.

Expecting to hear only waves lapping against the keel of a boat, the sound of laughter in the next room knocked me unwillingly back into the twenty-first century. I blinked to rid myself of the last phantom images of tarry decks and canvas sails. It took me a moment to remember where I was; my head felt as muzzy as though I’d just taken a double dose of cold medicine. A quick glance around informed me that I was still sprawled out on the Persian rug in Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s drawing room and the fire next to me had burned down to mere embers from lack of tending. I had no idea what time it was, or how long I’d been reading, but one leg seemed to have gone numb, and there was a vague ache in my shoulders.

I was experimentally stretching out one stiff leg—just to make sure it still worked—when he appeared in the doorway.

It was the Golden Man. He of the photograph on Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s mantel. For a moment, in my befuddled state, caught between past and present, I half fancied that he’d just strolled out of the photograph. All right, I know it sounds silly, but I actually took a quick look to make sure the man in the picture was still where he ought to be, frozen in perpetual laughter next to his horse. He was. And on a second glance at the man in the doorway, I picked up the differences I had missed the first time around. The man in the photograph hadn’t been wearing gray slacks and a blazer, and his blond hair had been bright with sun, not dark with wet.

He also hadn’t been wearing an unspeakably chic woman on his arm.

She was about my height, but there the resemblance ended. Her long, glossy dark brown hair floated around her face as though it was auditioning for a Pantene commercial. Her brown suede boots were as immaculate as if she had just walked out of the Harrods shoe department, and her smart little brown wool dress screamed Notting Hill boutique. They made an attractive pair, like something out of Town and Country: Mr. and Mrs. Fabulously Fabulous Show Off their Gracious Home.

It was enough to make one feel like a miserable mugwump.

I was so deep in mugwump land that it took me a moment to realize that not only was the smiling, golden man of the photograph not smiling, his expression was positively explosive. And it was aimed at me.

“Hi!” I struggled to my feet, a few yellowed pages tumbling from my lap as I levered myself up with one hand, the other hand clutching the bundle of letters. “I’m Elo—”

Golden Man stalked across the drawing room, snatched up the papers I’d left on the floor, flung them into the open chest, and slammed the lid shut.

“Who gave you leave to take those papers?”

I was so shocked by the transformation of the friendly man of the photograph that my brain and my mouth stopped working in partnership.

“Who gave me . . . ?” I glanced down dumbly at the papers in my hand. “Oh, these! Mrs. Selwick-Alderly said—”

Golden Man bellowed, “Aunt Arabella!”

“Mrs. Selwick-Alderly said I could—”

“Serena, would you go fetch Aunt Arabella?”

Chic Girl bit her lip. “I’ll just go see if she’s ready to leave, shall I?” she murmured, and hurried off down the hallway.

Golden Man plunked himself down on the chest, as though defying me to snatch it out from under him, and glowered at me.

I stared at him in dismayed confusion, automatically clutching Amy’s letters closer to my coffee-blotched sweater. Could he be under some sort of misapprehension about my intentions towards his family papers? Maybe he thought I was an appraiser from Britain’s equivalent of the IRS, come to charge his aunt great gobs of money for possessing a national treasure, or a rogue librarian, come to steal the papers for my library. After all, if there was art theft, maybe there was document theft, too, and he thought I was a dastardly document thief. I didn’t think I looked particularly dastardly, just disheveled—it’s hard to look dastardly when one has wide blue eyes, and one of those easy-to-blush complexions—but maybe document thieves came in all shapes and sizes.

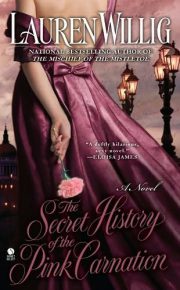

"The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" друзьям в соцсетях.