“In his defense, he wasn’t driving,” Rachel points out. Before I can respond, she holds up her hand. “But I get it. You saw that as a sign of impending alcoholism. Or bad decision making. Or… something.”

Elizabeth shakes her head. “You are way too fussy, Sierra.”

Rachel and Elizabeth always give me a hard time about my standards with guys. I’ve just watched too many girls end up with guys who bring them down. Maybe not at first, but eventually. Why waste years or months, or even days, on someone like that?

Before we reach the double doors that lead back into the halls, Elizabeth takes a step ahead and spins toward us. “I’m going to be late for English, but let’s meet up for lunch, okay?”

I smile because we always meet up for lunch.

We push our way into the halls and Elizabeth disappears into the bustle of students.

“Two more lunches,” Rachel says. She pretends to wipe tears from the corners of her eyes as we walk. “That’s all we get. It almost makes me want to—”

“Stop!” I say. “Don’t say it.”

“Oh, don’t worry about me.” Rachel waves her hand dismissively. “I’ve got plenty to keep me busy while you party it up in California. Let’s see, next Monday we’ll start tearing down the set. That should take a week or so. Then I’ll help the dance committee finish designing the winter formal. It’s not theater, but I like to use my talents where they’re needed.”

“Do they have a theme for this year yet?” I ask.

“Snow Globe of Love,” she says. “It sounds cheesy, I know, but I’ve got some great ideas. I want to decorate the whole gym to look like you’re dancing in the middle of a snow globe. So I’ll be plenty busy until you get back.”

“See? You’ll hardly miss me,” I say.

“That’s right,” Rachel says. She nudges me as we continue to walk. “But you’d better miss me.”

And I will. For my entire life, missing my friends has been a Christmas tradition.

CHAPTER TWO

The sun barely peeks up from behind the hills when I park Dad’s truck on the side of the muddy access road. I set the emergency brake and look out on one of my favorite views. The Christmas trees begin a few feet from the driver’s side window and continue for over a hundred acres of rolling hills. On the other side of the truck, our field continues just as far. Where our land ends on either side, more farms carry on with more Christmas trees.

When I turn off the heater and step outside, I know the cold air is going to bite. I pull my hair into a tight ponytail, tuck it down the back of my bulky winter jacket, bring the hood over my head, and then pull the drawstrings tight.

The smell of tree resin is thick in the wet air, and the damp soil tugs at my heavy boots. Branches scratch at my sleeves as I pull my phone from my pocket. I tap Uncle Bruce’s number and then hold the phone against my ear with my shoulder while I pull on work gloves.

He laughs when he answers. “It sure didn’t take you long to get up there, Sierra!”

“I wasn’t driving that fast,” I say. In truth, taking those turns and sliding through mud is way too fun to resist.

“Not to worry, honey. I’ve torn up that hill plenty of times in my truck.”

“I’ve seen you, which is how I knew it would be fun,” I say. “Anyway, I’m almost at the first bundle.”

“Be there in a minute,” he says. Before he hangs up, I can hear the helicopter motor start to turn.

From my jacket pocket, I remove an orange mesh safety vest and slip my arms through the holes. The Velcro strip running down the chest holds it in place so Uncle Bruce will be able to spot me from the air.

From maybe two hundred yards ahead, I can hear chainsaws buzz as workers carve through the stumps of this year’s trees. Two months ago, we began tagging the ones we wanted cut down. On a branch near the top we tied a colored plastic ribbon. Red, yellow, or blue, depending on the height, to help us sort them later while loading the trucks. Any trees that remain untagged will be left to continue growing.

In the distance, I can see the red helicopter flying this way. Mom and Dad helped Uncle Bruce buy it in exchange for his help airlifting our trees during the harvest. The helicopter keeps us from wasting land with crisscrossing access roads, and the trees get shipped fresher. The rest of the year, he uses it to fly tourists along the rocky coastline. Sometimes he even gets to play hero and find a lost hiker.

After the workers ahead of me cut four or five trees, they lay them side-by-side atop two long cables, like placing them across railroad tracks. They pile more trees on top until they’ve gathered about a dozen. Then they lace the cables over the bundle and cinch them together before moving on.

That’s where I come in.

Last year was the first year Dad let me do this. I knew he wanted to tell me the work was too dangerous for a fifteen-year-old girl, but he wouldn’t dare say that out loud. A few of the guys he hires to cut the trees are classmates of mine, and he lets them wield chainsaws.

The helicopter blades grow louder—thwump-thwump-thwump-thwump—slicing through the air. The beat of my heart matches their rhythm as I get ready to attach my first bundle of the season.

I stand beside the first batch, flexing my gloved fingers. The early sunlight flashes across the window of the helicopter. A long line of cable trails behind it, dragging a heavy red hook through the sky.

The helicopter slows as it approaches, and I dig my boots into the soil. Hovering above me, the blades boom. Thwump-thwump-thwump-thwump. The helicopter slowly lowers until the metal hook touches the needles of the bundled trees. I raise my arm over my head and make a circular motion to ask for more slack. When it lowers a few more inches, I grab the hook, slip it beneath the cables, and then take two large steps back.

Looking up, I can see Uncle Bruce smile down at me. I point at him, he gives me a thumbs-up, and then up he goes. The heavy bundle pulls together as it lifts from the ground, and then it sails away.

A crescent moon hangs over our farmhouse. Looking out from my upstairs window, I can see the hills roll off into deep shadows. As a child, I would stand here and pretend to be a ship’s captain watching the ocean at night, the swells often darker than the starry sky above.

This view remains constant each year because of how we rotate the harvest. For each tree cut, we leave five in the ground and plant a new seedling in its place. In six years, all of these individual trees will have been shipped around the country to stand in homes as the centerpiece of the holidays.

Because of this, my season has different traditions. The day before Thanksgiving, Mom and I will drive south and reunite with Dad. Then we’ll eat Thanksgiving dinner with Heather and her family. The next day we’ll start selling trees from morning to night, and we won’t stop until Christmas Eve. That night, exhausted, we’ll exchange one gift each. There isn’t room for many more gifts than that in our silver Airstream trailer—our home-away-from-home.

Our farmhouse was built in the 1930s. The old wooden floors and stairs make it impossible to get out of bed in the middle of the night without making noise, but I stick close to the least creaky side of the stairs. I’m three steps from the kitchen floor when Mom calls to me from the living room.

“Sierra, you need to get at least a few hours of sleep.”

Whenever Dad’s not here, Mom falls asleep on the couch with the TV on. The romantic side of me wants to believe their bedroom feels too lonely when he’s gone. My nonromantic side thinks falling asleep on the couch makes her feel rebellious.

I hold my robe around me and slip my feet into tattered sneakers by the couch. Mom yawns and reaches for the remote control on the floor. She turns off the TV, which blackens the room.

She clicks on a side lamp. “Where are you going?”

“To the greenhouse,” I say. “I want to bring the tree in here so we don’t forget it.”

Rather than loading our car the night before we leave, we place all of our bags near the front door so we can look them over one more time before the drive. Once we hit the highway, the road ahead is too long to turn back.

“And then you need to go right to bed,” Mom says. She shares my curse of not being able to sleep if I’m worried about something. “Otherwise, I can’t let you drive tomorrow.”

I promise her and close the front door, pulling my robe tighter to keep out the cold night air. The greenhouse will be warm, but I’ll be inside only long enough to grab the little tree, which I recently transplanted into a black plastic bucket. I’ll put that tree by our luggage and then Heather and I will plant it after dinner on Thanksgiving. This will make six trees, which started on our farm, that now grow atop Cardinals Peak in California. The plan for next year has always been to cut down the first one we planted and give it to Heather’s family.

That’s one more reason this can’t be our last season.

CHAPTER THREE

From outside, the trailer may look like a silver thermos tipped on its side, but the inside has always felt cozy to me. A small dining table is attached to the wall at one end, with the edge of my bed doubling as one of the benches. The kitchen is compact with a sink, refrigerator, stove, and microwave. The bathroom feels smaller every year even though my parents upgraded for a bigger shower. With a standard shower, it would have been impossible to reach down and wash my legs without doing stretches first. At the other end of the trailer from my bed is the door to Mom and Dad’s room, which has barely enough space for their bed, a small closet, and a footstool. Their door is shut now, but I can hear Mom snoring as she recovers from our long drive.

The foot of my bed touches the kitchen cabinet, and there’s a wooden cupboard above it. I press a large white thumbtack into the cupboard. On the table beside me are the picture frames from Rachel and Elizabeth. I’ve connected them with shiny green ribbon so they’ll hang one on top of the other. I tie a loop at the end of the ribbon and hook it onto the thumbtack so my friends back home can be with me every day.

“Welcome to California,” I tell them.

I scoot to the head of my bed and slide the curtains apart.

A Christmas tree topples against the window and I scream. The needles scratch the glass as someone struggles to pull the tree upright again.

Andrew peeks around the branches, probably to make sure he didn’t bust the glass. He blushes when he sees me, and I glance down to make sure I put on a shirt after showering. Over the years I have taken a few morning showers and then walked around the trailer in a towel before remembering a lot of high school guys work right outside.

Last year, Andrew became the first and the last guy to ask me out down here. He did it with a note taped to the other side of my window. It was meant to look cute, I guess, but what I pictured was him tiptoeing in the dark mere inches from where I slept. Thankfully, I was able to tell him it wouldn’t be smart to date anyone who works here. That’s not an actual rule, but my parents have mentioned a few times how uncomfortable that might be for everyone involved since they work here, too.

Mom and Dad met when they were my age, and he worked with his parents on this very lot. Her family lived a few blocks away, and one winter they fell so hard for each other, he returned for baseball camp that summer. After they married and took over the lot, for extra help they began hiring ballplayers from the local high school who wanted extra holiday cash. This was never a problem when I was young, but once I entered puberty, new and thicker curtains were hung up around the trailer.

While I can’t hear Andrew, I see him mouth “Sorry” from the other side of the window. He finally gets the tree upright and then shimmies the stand back a few feet so the lower branches don’t touch any tree around it.

There’s no reason to let our past awkwardness keep us from being cordial, so I slide the window partly open. “So you’re back for another year,” I say.

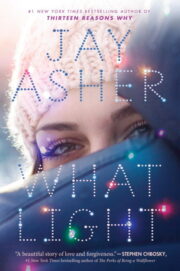

"What Light" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "What Light". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "What Light" друзьям в соцсетях.