“I’m going to pass on the double-dating,” I say. “But thanks.”

“Don’t thank me yet,” she says. “I’ll probably bring it up again.”

After the next turn, which takes us near the top of Cardinals Peak, Heather and I step off the narrowing dirt road and into knee-high brush. She sweeps her flashlight back and forth. What sounds like a small rabbit bounds away.

Another dozen steps and the brush mostly clears. It’s too dark to see all five Christmas trees at once, but when Heather’s flashlight hits the first one, my heart warms. She slowly scans the beam until I see them all. We spaced them several feet apart so one won’t overshadow another in the sunlight. The tallest is already a few inches taller than me, and the smallest barely reaches my waist.

“Hey, guys,” I say as I walk among them. Still holding the newest tree with one arm, I touch the needles of the other trees with my free hand.

“I came up last weekend,” Heather says. “I pulled some weeds and loosened the ground a bit so tonight will be easier.”

I set the burlap sack on the dirt and then face Heather. “You are becoming Little Miss Farmer Girl.”

“Hardly,” she says. “But last year it took us forever to clear the weeds after dark, so—”

“Either way, I’m going to pretend you enjoyed yourself,” I say. “And whatever the reason, you would not have done it unless you were an awesome friend. So thank you.”

Heather politely nods and then hands me the trowel.

I look around until I find the perfect spot. A new tree, I believe, should always get the best view of what’s happening below. After I kneel into the dirt, which is soft thanks to Heather, I begin digging a hole large enough to contain the roots.

The last two years we made the trek, we took turns carrying the tree. Before that we wheeled it up here in Heather’s red wagon. It has become like my own little tree farm, a way to keep a part of me here after my family heads back north.

I wonder again if, next year, I’ll have the chance to cut down the oldest tree.

This season was supposed to be perfect, not bogged down with what-ifs. They’re all around me, though, in everything I do. I don’t know how to fully enjoy any of these moments without wondering if it’s the last.

I untie the twine that holds the burlap around the roots. When I peel the fabric away, the roots stay mostly in place, still covered in soil from back home.

“I’m going to miss these hikes,” Heather says.

I set the tree into the hole and spread out some of the roots with my fingers.

Heather kneels beside me and helps me scoop dirt back into the hole. “At least we have one more year,” she says.

Unable to look at her, I sprinkle another handful of soil around the base of the tree. I clap the dirt from my hands and then sit on the ground. Pulling my knees to my chest, I look down the dark hill to the city lights. Out there Heather has lived her entire life. Though I may stay here only a short while each year, I feel like I’ve grown up here, too. I exhale a deep breath.

“What’s the matter?” Heather asks.

I look up at her. “There may not be another year.”

She looks at me with a furrowed brow but doesn’t speak.

“They won’t say it to me,” I tell her, “but I’ve overheard my parents discussing this for a while. They might not be able to justify coming down here another season.”

Now Heather looks out at the town.

From this high up, when the season gets under way and all the lights go on, it’s easy to spot our Christmas tree lot. Starting tomorrow, a rectangle of white lights will surround our trees. But tonight, the place where I live is a dark patch near a long street with headlights driving past.

“This year will tell us for sure,” I say. “I know my parents want to be here as much as I do. Rachel and Elizabeth, on the other hand, love the idea of me staying in Oregon for Christmas.”

Heather sits down on the dirt beside me. “You’re one of my best friends, Sierra. And I know Rachel and Elizabeth feel the same way, so I can’t blame them—but they get you the whole rest of the year. I can’t imagine you and your family not being a part of my holidays.”

I really don’t want to miss my last full season with Heather, either. It’s something we’ve known was coming from the beginning. We’ve talked about senior year with such apprehensive anticipation.

“I feel the same way,” I tell her. “I mean, I am curious about what the holidays would be like back home—not dealing with school online and getting to do Decemberish things in my hometown for once.”

Heather looks up at the stars for a long time.

“But I would miss you,” I say, “and all of this way too much.”

I see her smile. “Maybe I could come up there for a few days, visit you over the break for once.”

I lean my head against her shoulder and look out. Not up at the stars or down at the town, but away.

Heather leans her head against mine. “Let’s not worry about it right now,” she says, and neither of us say anything more for several minutes.

Eventually, I turn back to the smallest tree. I pat the soil around it and slide some more dirt toward its thin trunk. “Let’s make this year extra special no matter what,” I say.

Heather stands up and looks out at the town. I take her hand and she helps me up. I stand beside her, not letting go.

“What would be amazing,” she says, “is if we put lights on these trees so they could be seen by everyone down there.”

It’s a beautiful thought, a way to share our friendship with everyone. I could open the curtains over my bed and look up at them every night to fall asleep.

“But I checked on the hike up,” she says. “This mountain doesn’t have a single electrical outlet.”

I laugh. “The nature in this town is so behind the times.”

CHAPTER FIVE

With my eyes still closed, I hear Mom and Dad shut the door as they leave the trailer. I roll onto my back and take a deep breath. A few extra moments are all I want. Once I get out of bed, the days will tumble forward like dominoes.

On opening day, Mom always wakes up ready to go. I’m much more like Dad, and I can hear his heavy boots on the dirt outside, shuffling toward the Bigtop. Once there, he’ll plug in a large silver urn of coffee and one of hot water, and then arrange the packets of tea and powdered chocolate that we put out for customers. The first hot drops of coffee will be poured into his thermos, though.

I pull the tube-shaped pillow from under my head and hug it against my chest. After Heather’s mom competes in the ugly Christmas sweater contest, which she’s won twice in the past six years, she cuts off the sleeves and makes them into bolster pillows. She sews up the cuff end, stuffs the sleeve with cotton, and then sews up the other end. She keeps one sleeve for her family and the other one goes to me.

I hold the one I got last night at arm’s length above me. It’s a mossy green fabric with a dark blue rectangle where the elbow was. Within that rectangle, snowflakes fall around a flying purple-nosed reindeer.

I cuddle the pillow tight and close my eyes again. Outside, I hear someone moving toward the trailer.

“Is Sierra around?” Andrew asks.

“Not right now,” Dad says.

“Oh, okay,” Andrew says. “I figured we could work together and get things done faster.”

I squeeze the pillow even tighter. I do not need Andrew waiting outside for me.

“I believe she’s still sleeping,” Dad says. “But if you need something to do by yourself, double-check the outhouses for hand sanitizer.”

That’s my dad!

I stand outside the Bigtop, still not fully awake but ready to welcome our first customers of the year. A father and his daughter, who’s maybe seven years old, step out of their car. Already scanning the trees, he places a gentle hand on her head.

“I always love this smell,” the father says.

The girl takes a step forward, her eyes full of sweet innocence. “It smells like Christmas!”

It smells like Christmas. This is what so many people say when they first arrive, as if the words were waiting to be spoken the entire drive over.

Dad appears from between two noble firs on his way to the Bigtop, probably hoping for more coffee. First, he greets the family and tells them to let any of us know if we can help. Andrew, in a tattered Bulldogs baseball cap, walks by with a watering hose draped over his shoulder. He tells the family he’ll be happy to carry a tree to their car when they’re ready. He doesn’t even glance in at me—thanks to Dad—and I bite down on a grin.

“Is your cash drawer ready?” Dad asks, refilling his thermos.

I walk behind the checkout counter, which has been draped in shiny red garland and fresh holly. “Just waiting to see what the first sell will be.”

Dad hands me my favorite mug, painted with pastel squiggles and stripes like an Easter egg (I figure there should be something around here that’s not Christmassy). I pour in some coffee and then tear open a packet of powdered chocolate and dump it in. Then I unwrap a small peppermint candy cane and use it to mix it all together.

Dad leans his back against the counter, surveying the merchandise in the Bigtop. He points his thermos at the snow-white trees he finished spraying this morning. “Do you think we have enough of these for now?”

I lick chocolate powder from the thinning candy cane and then drop it back into the mug. “We have plenty,” I say, and then I take my first sip. It may taste like a cheap peppermint mocha, but it works.

Eventually, that first father and daughter come into the Bigtop and stop at the cash register.

I lean over the counter toward the little girl. “Did you find a tree you like?”

She nods enthusiastically, a tooth adorably missing from the top of her smile. “A huge one!”

It’s our first sale of the year and I can’t suppress my excitement, along with a deep-rooted hope that we’ll do well enough this year to justify at least one more.

The father slides a tree tag across the counter to me. Behind him, I can see Andrew pushing their tree, trunk first, through the open end of a large plastic barrel. At the other end is a screen of red-and-white netting. Dad grabs the trunk and pulls the rest of the tree out with the netting, which unfurls and wraps around the branches. Once through, the branches are all folded safely upward. Dad and Andrew twist the tree in the netting, cut the end free, and tie a knot at the top. The process is similar to how Heather’s mom stuffs her sweater sleeves to make pillows, except way less ugly.

I ring up our first tree and wish them both a “Merry Christmas!”

At lunch, my legs are tired and achy from loading trees and standing behind the register for hours on end. In a few days, I’ll be more used to this, but today I’m grateful when Heather shows up holding a bag of Thanksgiving leftovers. Mom shoos us off into the Airstream, and the first thing Heather does when we sit at the table is open the curtains wide.

She lifts her eyebrows at me. “Just improving the view.”

As if on cue, two guys from the baseball team walk by carrying a large tree on their shoulders.

“You have no shame.” I unwrap a turkey-and-cranberry sandwich. “Remember, you’re still with Devon until after Christmas.”

She pulls up her feet to sit cross-legged on the bench, also known as my bed, and unwraps her own sandwich. “He called last night and went into this twenty-minute story about going to the post office.”

“So he’s not a great conversationalist,” I say. I take the first bite of my sandwich and practically hum when the Thanksgiving flavors hit my tongue.

“You don’t understand. He told me that same story last week and it was just as pointless then.” When I laugh, she throws her hands in the air. “I’m serious! I don’t care about that grumpy old lady in front of him trying to ship a box of oysters to Alaska. Would you?”

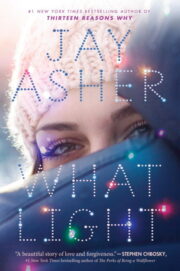

"What Light" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "What Light". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "What Light" друзьям в соцсетях.