"What time is supper, Mrs. Landry?" Paul asked. Grandmère Catherine shifted her eyes toward Paul's parents before replying.

"Supper is at six," Grandmère told him, and then went to join her friends for a chat. Paul waited until she was out of earshot.

"Everyone was talking about your grandfather this morning," he told me.

"Grandmère and I sensed that when we arrived. Did your parents find out you helped me get him home?"

The look on his face gave me the answer.

"I'm sorry if I caused you trouble."

"It's all right," he said quickly. "1 explained everything." He grinned cheerfully. He was the perpetual cockeyed optimist, never gloomy, doubtful, or moody, as I often was.

"Paul," his mother called. With her face frozen in a look of disapproval, her mouth was like a crooked knife slash and her eyes were long and catlike. She held her body stiffly, looking as if she would suddenly shudder and march away.

"Coming," Paul said.

His mother leaned over to whisper something to his father and his father turned to look my way.

Paul got most of his good looks from his father, a tall, distinguished looking man who was always elegantly dressed and well-groomed. He had a strong mouth and jaw with a straight nose, not too long or too narrow.

"We're leaving right this minute," his mother emphasized.

"I've got to go. We have some relatives coming for lunch. See you later," Paul promised, and he darted off to join his parents.

I stepped beside Grandmère Catherine just as she invited Mrs. Livaudis and Mrs. Thibodeau to our house for coffee and blackberry pie. Knowing how slowly they would walk, I hurried ahead, promising to start the coffee. But when I got to our front yard, I saw my grandfather down at the dock, tying his pirogue to the back of the dingy.

"Good morning, Grandpère," I called. He looked up slowly as I approached.

His eyes were half-closed, the lids heavy. His hair was wild, the strands in the back flowing in every direction over his collar. I imagined that the tin drum Paul predicted was banging away in Grandpère's head. He looked grouchy and tired. He hadn't changed out of the clothes he had slept in and the stale odor of last night's rum whiskey lingered on him. Grandmère Catherine always said the best thing that could happen to him was for him to fall into the swamp. "That way, at least he'd get a bath."

"You bring me back to my shack in the swamp last night?" he asked quickly.

"Yes, Grandpère. Me and Paul."

"Paul? Who's Paul?"

"Paul Tate, Grandpère."

"Oh, a rich man's son, eh? Them cannery people ain't much better than the oil riggers, dredging the swamp to make it wider for their damn big boats. You got no business hanging around that sort. There's only one thing they want from the likes of you," he warned.

"Paul's very nice," I said sharply. He grunted and continued to tie his knot.

"Coming from church, are ya?" he asked without looking up.

"Yes."

He paused and looked back toward the road.

"Your Grandmère's still gabbin' with those other busybodies, I imagine. That's why they go to church," he claimed, "to nourish gossip."

"It was a very nice service, Grandpère. Why don't you ever go?"

"This here is my church," he declared, and waved his long fingers at the swamp. "I got no priest lookin' over my shoulder, spitting hell and damnation down my back." He stepped into the dingy.

"Would you like a cup of fresh coffee, Grandpère? I'm about to make some. Grandmère has some of her friends coming for blackberry pie and—"

"Hell no. I wouldn't be caught dead with those fishwives." He shifted his eyes to me and softened his gaze. "You look nice in that dress," he said. "Pretty as your mother was."

"Thank you, Grandpère."

"I guess you cleaned up my shack some, too, didn't you?" I nodded. "Well, thanks for that."

He reached for the cord to pull and start his motor.

"Grandpère," I said, approaching. "You were talking about someone who was in love and something about money, last night after we brought you home."

He paused and looked at me hard, his eyes turning to granite very quickly.

"What else did I say?"

"Nothing. But what did you mean, Grandpère? Who was in love?"

He shrugged.

"Probably remembered one of the stories my father told me about his father and Grandpère. Our family goes way back to the riverboat gamblers, you know," he said with some pride. "Lots of money traveled through Landry fingers," he said, holding up his muddied hands, "and each of the Landrys cut quite a romantic figure on the river. Lots of women were in love with them. You could line them up from here to New Orleans."

"Is that why you gamble away all your money? Grandmère says it's in the Landry blood," I said.

"Well, she ain't wrong about that. I'm just not as good at it as some of my kinfolk was." He leaned forward, smiling, the gaps in his teeth dark and wide where he had pulled out his own when the aches became too painful to manage. "My great, great-Grandpère, Gib Landry, was a sure-thing player. Know what that was?" he asked. I shook my head. "A player who never lost because he had marked cards." He laughed. "They called them 'Vantage tools.' Well, they certainly gave an advantage." He laughed again.

"What happened to him, Grandpère?"

"He was shot to death on the Delta Queen. When you live hard and dangerous, you're always gambling," he said, and pulled the cord. The motor sputtered. "Someday, when I got the time, I'll tell you more about your ancestors. Despite what she tells you," he added, nodding toward the house, "you oughta know something about them." He pulled the cord again and ,this time the motor caught and began to rumble. "I gotta get goin'. I got some oysters to catch."

"I wish you could come to dinner at the house tonight and meet Paul," I said. What I really meant was I wish we were a family.

"What do you mean, meet Paul? Your Grandmère invited him to dinner?" he asked skeptically.

"I did. She said it was all right."

He stared at me a long moment and then turned back to his motor.

"Got no time for socializin'. Gotta make me a livin'."

Grandmère Catherine and her friends appeared on the road behind us. I saw Grandpère Jack's eyes linger for a moment and then he sat himself down quickly.

"Grandpère," I cried, but he gunned his motor and turned the dingy to pull away as quickly as he could and head for one of the shallow brackish lakes scattered through the marshes. He didn't look back. In moments, the swamp swallowed him up and only the growl of his motor could be heard as he wound his way through the channels.

"What did he want?" Grandmère Catherine demanded.

"Just to get his dingy."

She kept her eyes fixed on his wake as if she expected he would reappear. She glared and narrowed her eyes into slits as if she were willing the swamp to swallow him up forever. Soon, the sound of his dingy motor died away and Grandmère Catherine straightened herself up again and smiled at her two friends. They quickly returned to their conversation and entered the house, but I lingered a moment and wondered how these two people could have ever been in love enough to marry and have a daughter. How could love or what you thought was love make you so blind to each other's weaknesses?

Later that day, after Grandmère Catherine's friends left, I helped her prepare our supper. I wanted to ask her more about Grandpère Jack, but those questions usually put her in a bad mood. With Paul coming for supper, I dared not risk it.

"We're not doing anything special for supper tonight, Ruby," she told me. "I hope you didn't give the Tate boy that impression."

"Oh, no, Grandmère. Besides, Paul isn't that kind of a boy. You wouldn't even know his family was wealthy. He's so different from his mother and his sisters. Everyone in school says they're stuck-up, but not Paul."

"Maybe, but you don't live the way the Tates live and not get to expect certain things. It's just human nature. The higher you build him up in your mind, Ruby, the harder the fall of disappointment is going to be," she warned.

"I'm not afraid of that, Grandmère," I said with such certainty that she paused to gaze at me.

"You've been a good girl, haven't you, Ruby?"

"Oh, yes, Grandmère."

"Don't ever forget what happened to your mother," she admonished.

For a while I feared Grandmère Catherine would hold this cloud of dread over the house up until and through our dinner, but despite her claim that we weren't having anything special, few things pleased Grandmère Catherine as much as cooking for someone she knew would appreciate it. She set out to make one of her best Cajun dishes: jambalaya. While I helped with that, Grandmère made a custard pie.

"Was my mother a good cook, too, Grandmère?" I asked her.

"Oh, yes," she said, smiling at the memories. "No one picked up recipes as quickly and as well as your mother did. She was cooking gumbo before she was nine years old, and by the time she was twelve, no one could clear out the icebox and make as good a jambalaya.

"When your Grandpère Jack was still something of a human being," she continued, "he would take Gabrielle out and show her all the edible things in the swamp. She learned fast, and you know what they say about us Cajuns," Grandmère added, "we'll eat anything that doesn't eat us first."

She laughed and hummed one of her favorite tunes. On Sundays we usually gave the house a good once-over anyway, but this special Sunday, I went at it with more energy and concern, washing down the windows until every speck of dirt was gone, scrubbing the floors until they shone, and dusting and polishing everything in sight.

"You'd think the king of France was coming here tonight," Grandmère teased. "I'm warning you, Ruby, don't let that boy expect more of you than there is."

"I won't, Grandmère," I said, but in my secret putaway heart, I hoped that Paul would be very impressed and brag about us to his parents so much they would drop any opposition they might have to his making me his girlfriend.

By late afternoon, our little home nearly sparkled and was filled with delicious aromas. As the clock ticked closer to six, I grew more and more excited. I hoped that Paul would be early, so I sat outside and waited the last hour with my eyes fixed in the direction he would come. Our table was set and I wore my best dress. Grandmère Catherine had made it herself. It was white with a deep lace hem and a lace panel down the front. The sleeves were soft bells of lace that came to my elbows. I wore a blue sash around my waist.

"I'm glad I let out that bodice some," she said when she saw me. "The way your bosom's blossoming. Turn around," she said, and smoothed out the back of the skirt. "I must say, you're turning out to be a real belle, Ruby. Even more beautiful than your mother was at your age."

"I hope I'm as pretty as you are at your age, Grandmère," I replied. She shook her head and smiled.

"Go on now. I'm enough to scare a marsh hawk to death," she said, and laughed, but for the first time, I got Grandmère Catherine to tell me about some of her old boyfriends and some of the fais dodos she had attended when she was my age.

When the clock struck six, I lifted my eyes in anticipation, expecting Paul's motor scooter to rumble moments later. But it didn't and the road remained quiet and still. After a little while Grandmère came to the door and peered out herself. She gazed sadly at me and then returned to the kitchen to do some final things. My heart began to pound. The breeze became more of a wind; all of the trees waving their branches. Where was he? At about seven, I became very concerned and when Grandmère Catherine appeared in the doorway again, she wore a look of fatal acceptance on her face.

"It's not like him to be late," I said. "I hope nothing has happened to him."

Grandmère Catherine didn't reply; she didn't have to. Her eyes said it all.

"You'd better come in and sit down, Ruby. We made the food and want to enjoy it anyway."

"He's coming, Grandmère. I'm sure he's coming. Something unexpected must have happened," I cried. "Let me wait just a little while longer," I pleaded. She retreated, but at seven-fifteen she came to the door again.

"We can't wait any longer," she declared.

Dejected, all my appetite gone anyway, I rose and went inside. Grandmère Catherine said nothing. She served the meal and sat down.

"This came out as good as it ever has," she declared. Then leaning toward me, she added, "even if I have to say so myself."

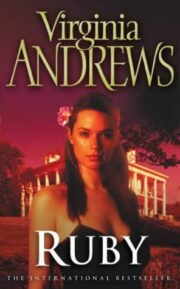

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.