Wasn’t that just like Shropshire?

Sinking to the grass, Amy contemplated the place where she had spent the majority of her life. Behind her, over the rolling fields, the redbrick manor house sat placidly on its rise. Uncle Bertrand was sure to be right there, three windows from the left, sitting in his cracked leather chair, poring over the latest findings of the Royal Agricultural Society, just as he did every day. Aunt Prudence would be sitting in the yellow-and-cream morning room, squinting over her embroidery threads, just as she did every day. All peaceful, and bucolic, and boring.

The prospect before her wasn’t any more exciting, nothing but long swaths of green, enlivened only by woolly balls of sheep.

But now, at last, the long years of boredom were at an end. In her hand she grasped the opportunity to leave Wooliston Manor and its pampered flock behind her forever. She would no longer be plain Amy Balcourt, niece to the most ambitious sheep breeder in Shropshire, but Aimée, Mlle de Balcourt. Amy conveniently ignored the fact that revolutionary France had banished titles when they beheaded their nobility.

She had been six years old when revolution exiled her to rural England. In late May of 1789, she and Mama had sailed across the Channel for what was meant to be merely a two-month visit, time enough for Mama to see her sisters and show her daughter something of English ways. For all the years she had spent in France, Mama was still an Englishwoman at heart.

Uncle Bertrand, sporting a slightly askew periwig, had stridden out to meet them. Behind him stood Aunt Prudence, embroidery hoop clutched in her hand. Clustered in the doorway were three little girls in identical muslin dresses, Amy’s cousins Sophia, Jane, and Agnes. “See, darling,” whispered Mama. “You shall have other little girls to play with. Won’t that be lovely?”

It wasn’t lovely. Agnes, still in the lisping and stumbling stage, was too young to be a playmate. Sophia spent all of her time bent virtuously over her sampler. Jane, quiet and shy, Amy dismissed as a poor-spirited thing. Even the sheep soon lost their charm. Within a month, Amy was quite ready to return to France. She packed her little trunk, heaved and pushed it down the hall to her mother’s room, and announced that she was prepared to go.

Mama had half-smiled, but her smile twisted into a sob. She plucked her daughter off the trunk and squeezed her very, very tightly.

“Mais, maman, qu’est-ce que se passe?” demanded Amy, who still thought in French in those days.

“We can’t go back, darling. Not now. I don’t know if we’ll ever . . . Oh, your poor father! Poor us! And Edouard, what must they be doing to him?”

Amy didn’t know who they were, but remembering the way Edouard had yanked at her curls and pinched her arm while supposedly hugging her good-bye, she couldn’t help but think her brother deserved anything he got. She said as much to Mama.

Mama looked down at her miserably. “Oh no, darling, not this. Nobody deserves this.” Very slowly, in between deep breaths, she had explained to Amy that mobs had taken over Paris, that the king and queen were prisoners, and that Papa and Edouard were very much in danger.

Over the next few months, Wooliston Manor became the unlikely center of an antirevolutionary movement. Everyone pored over the weekly papers, wincing at news of atrocities across the Channel. Mama ruined quill after quill penning desperate letters to connections in France, London, Austria. When the Scarlet Pimpernel appeared on the scene, snatching aristocrats from the sharp embrace of Madame Guillotine, Mama brimmed over with fresh hope. She peppered every news sheet within a hundred miles of London with advertisements begging the Scarlet Pimpernel to save her son and husband.

Amidst all this hubbub, Amy lay awake at night in the nursery, wishing she were old enough to go back to France herself and save Papa. She would go disguised, of course, since everyone knew a proper rescue had to be done in disguise. When no one was about, Amy would creep down to the servants’ quarters to try on their clothes and practice speaking in the rough, peasant French of the countryside. If anyone happened upon her, Amy explained that she was preparing amateur theatricals. With so much to worry about, none of the grown-ups who absently said, “How nice, dear,” and patted her on the head ever bothered to wonder why the promised performance never materialized.

Except Jane. When Jane came upon Amy clad in an assortment of old petticoats from the ragbag and a discarded periwig of Uncle Bertrand’s, Amy huffily informed her that she was rehearsing for a one-woman production of Two Gentlemen of Verona.

Jane regarded her thoughtfully. Half apologetically, she said, “I don’t think you’re telling the truth.”

Unable to think of a crushing response, Amy just glared. Jane clutched her rag doll tighter, but managed to ask, “Please, won’t you tell me what you’re really doing?”

“You won’t tell Mama or any of the others?” Amy tried to look suitably fierce, but the effect was quite ruined by her periwig sliding askew and dangling from one ear.

Jane hastily nodded.

“I,” declared Amy importantly, “am going to join the League of the Scarlet Pimpernel and rescue Papa.”

Jane pondered this new information, doll dangling forgotten from one hand.

“May I help?” she asked.

Her cousin’s unexpected aid proved a boon to Amy. It was Jane who figured out how to rub soot and gum on teeth to make them look like those of a desiccated old hag—and then how to rub it all off again before Nanny saw. It was Jane who plotted a route to France on the nursery globe and Jane who discovered a way to creep down the back stairs without making them creak.

They never had the chance to execute their plans. Little beknownst to the two small girls preparing themselves to enter his service, the Scarlet Pimpernel foolishly attempted the rescue of the Vicomte de Balcourt without them. From the papers, Amy learned that the Pimpernel had spirited Papa out of prison disguised as a cask of cheap red wine. The rescue might have gone without a hitch had a thirsty guard at the gates of the city not insisted on tapping the cask. When he encountered Papa instead of Beaujolais, the guard angrily sounded the alert. Papa, the papers claimed, had fought manfully, but he was no match for an entire troop of revolutionary soldiers. A week later, a small card had arrived for Mama. It said simply, “I’m sorry,” and was signed with a scarlet flower.

The news sent Mama into a decline and Amy into a fury. With Jane as her witness, she vowed to avenge Papa and Mama as soon as she was old enough to return to France. She would need excellent French for that, and Amy could already feel her native tongue beginning to slip away under the onslaught of constant English conversation. At first, she tried conversing in French with their governesses, but those worthy ladies tended to have a vocabulary limited to shades of cloth and the newest types of millinery. So Amy took her Molière outside and read aloud to the sheep.

Latin and Greek would do her no good in her mission, but Amy read them anyway, in memory of Papa. Papa had told her nightly bedtime stories of capricious gods and vengeful goddesses; Amy tracked all his stories down among the books in the little-used library at Wooliston Manor. Uncle Bertrand’s own taste ran more towards manuals on animal husbandry, but someone in the family must have read once, because the library possessed quite a creditable collection of classics. Amy read Ovid and Virgil and Aristophanes and Homer. She read dry histories and scandalous love poetry (her governesses, who had little Latin and less Greek, naïvely assumed that anything in a classical tongue must be respectable), but mostly she returned again and again to The Odyssey. Odysseus had fought to go home, and so would Amy.

When Amy was ten, the illustrated newsletters announced that the Scarlet Pimpernel had retired upon discovery of his identity—although the newsletters were rather unclear as to whether they or the French government had been the first to get the scoop. SCARLET PIMPERNEL UNMASKED! proclaimed the Shropshire Intelligencer. Meanwhile The Cosmopolitan Lady’s Book carried a ten-page spread on “Fashions of the Scarlet Pimpernel: Costume Tips from the Man Who Brought You the French Aristocracy.”

Amy was devastated. True, the Pimpernel had botched her father’s rescue, but, on the whole, his tally of aristocrats saved was quite impressive, and who on earth was she to offer her French language skills to if the Pimpernel retired? Amy was all ready to start constructing her own band when a line in the article in the Shropshire Intelligencer caught her eye. “I have every faith that the Purple Gentian will take up where I was forced to leave off,” they reported Sir Percy as saying.

Puzzled, Amy shoved the paper at Jane. “Who is the Purple Gentian?”

The same question was on everyone else’s lips. Soon the Purple Gentian became a regular feature in the news sheets. One week, he spirited fifteen aristocrats out of Paris as a traveling circus. The Purple Gentian, it was whispered, had played the dancing bear. Why, some said Robespierre himself had patted the animal on the head, never knowing it was his greatest enemy! When France stopped killing its aristocrats and directed its attention to fighting England instead, the Purple Gentian became the War Office’s most reliable spy.

“This victory would never have happened, but for the bravery of one man—one man represented by a small purple flower,” Admiral Nelson announced after destroying the French fleet in Egypt.

English and French alike were united in their burning curiosity to learn the identity of the Purple Gentian. Speculation ran rife on both sides of the Channel. Some claimed the Purple Gentian was an English aristocrat, a darling of the London ton like Sir Percy Blakeney. Indeed, some said he was Sir Percy Blakeney, fooling the foolish French by returning under a different name. London gossip named everyone from Beau Brummel (on the grounds that no one could genuinely be that interested in fashion) to the Prince of Wales’s dissolute brother, the Duke of York. Others declared that the Purple Gentian must be an exiled French noble, fighting for his homeland. Some said he was a soldier; others said he was a renegade priest. The French just said he was a damned nuisance. Or they would have, had they the good fortune to speak English. Instead, being French, they were forced to say it in their own language.

Amy said he was her hero.

She only said it to Jane, of course. All of the old plans were revived, only this time it was the League of the Purple Gentian to whom Amy planned to offer her services.

But the years went by, Amy remained in Shropshire, and the only masked man she saw was her small cousin Ned playing at being a highwayman. At times Amy considered running away to Paris, but how would she even get there? With war raging between England and France, normal travel across the Channel had been disrupted. Amy began to despair of ever reaching France, much less finding the Purple Gentian. She envisioned a dreary future of pastoral peace.

Until Edouard’s letter.

“I thought I’d find you here.”

“What?” Amy was jolted out of her blissful contemplation of Edouard’s letter, as a blue flounce brushed against her arm.

A basket of wildflowers on Jane’s arm testified to a walk along the grounds, but she bore no sign of outdoor exertion. No creases dared to settle in the folds of her muslin dress; her pale brown hair remained obediently coiled at the base of her neck; and even the loops of the bow holding her bonnet were remarkably even. Aside from a bit of windburn on her pale cheeks, she might have been sitting in the parlor all afternoon.

“Mama has been looking all over for you. She wants to know what you did with her skein of rose-pink embroidery silk.”

“What makes her think I have it? Besides,” Amy cut off what looked to be a highly logical response from Jane with a wave of Edouard’s letter, “who can think of embroidery silks when this just arrived?”

“A letter? Not another love poem from Derek?”

“Ugh!” Amy shuddered dramatically. “Really, Jane! What a vile thought! No”—she leaned forward, lowering her voice dramatically—“it’s a letter from Edouard.”

“Edward?” Jane, being Jane, automatically gave the name its English pronunciation. “So he has finally deigned to remember your existence after all these years?”

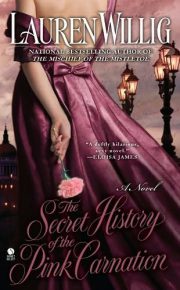

"The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" друзьям в соцсетях.