Richard found his quarry in the library.

“Selwick!” The Honorable Miles Dorrington flung aside the news sheet he had been reading, leaped up from his chair and pounded his friend on the back. He then hastily reseated himself, looking slightly abashed at his unseemly display of affection.

In a fit of temper, Richard’s sister Henrietta had once referred irritably to Miles as “that overeager sheepdog,” and there was something to be said for the description. With his sandy blond hair flopping into his face, and his brown eyes alight with good fellowship, Miles did bear a striking resemblance to the more amiable varieties of man’s best friend. He was, in fact, Richard’s best friend. They had been fast friends since their first days at Eton.

“When did you get back to London?” Miles asked.

Richard dropped into the seat next to him, sinking contentedly into the worn leather chair. He stretched his long legs comfortably out in front of him. “Late last night. I left Paris Thursday, stopped for a couple of nights at Uppington Hall, and got into town about midnight.” He grinned at his friend. “I’m in hiding.”

Miles instantly stiffened. Anxiously, he looked left, then right, before leaning forward and hissing, “From whom? Did they follow you here?”

Richard shouted with laughter. “Good God, nothing like that, man! No, I’m a fugitive from my mother.”

Miles relaxed. “You might have said so,” he commented crossly. “As you can imagine, we’re all a bit on edge.”

“Sorry, old chap.” Richard smiled his thanks as a glass of his favorite brand of scotch materialized in his hands. Ah, it was good to be back at his club!

Miles accepted a whisky, and leaned back in his chair. “What is it this time? Is she throwing another distant cousin at you?”

“Worse,” Richard said. He took a long swig of scotch. “Almack’s.”

Miles grimaced in sympathy. “Not the knee breeches.”

“Knee breeches and all.”

There was a moment of companionable silence as the men, both fashionably turned out in tight tan trousers, contemplated the horror of knee breeches. Miles finished his whisky and set it down on a low table beside his chair. Taking a more thorough look around the room, he asked Richard quietly, “How is Paris?”

Not only Richard’s oldest and closest friend, Miles also served as his contact at the War Office. When Richard had switched from rescuing aristocrats to gathering secrets, the Minister of War had wisely pointed out that the best possible way to communicate with Richard was through young Miles Dorrington. After all, the two men moved in the same set, shared the same friends, and could frequently be seen reminiscing over the tables at White’s. Nobody would see anything suspicious about finding two old friends in hushed conversation. As an excuse for his frequent calls at Uppington House, Miles had put it about that he was thinking of courting Richard’s sister. Henrietta had entered into the deception with, to Richard’s big-brotherly mind, a little too much relish.

Richard took his own survey of the room, noting the back of a white head poking out over a chairback. He lifted an eyebrow quizzically at Miles.

Miles shrugged. “It’s only old Falconstone. Deaf as a post and fast asleep to boot.”

“And his son is one of ours. Right. Paris has been . . . busy.”

Miles tugged at his cravat. “Busy how?”

“Stop that, or you’ll have your valet baying for your blood.”

Miles looked sheepish and tried to rearrange the folds of his cravat, which had gone from being a perfect waterfall to simply falling all over.

“Lots of comings and goings from the Tuilleries—more than usual,” Richard continued. “I’ve sent a full report to the office. Along with some information helpfully compiled by our mutual friend Monsieur Delaroche at the Ministry of Police.” His lips curved in a grin of sheer glee.

“Good man! I knew you could do it! A list of all their agents in London—and right out from under Delaroche’s nose, no less! You do have the devil’s own luck.” Richard’s back was too far away to reach, so Miles slapped the arm of his chair appreciatively instead. “And your connections to the First Consul?”

“Better than ever,” Richard said. “He’s moved the collection of Egyptian artifacts into the palace.”

Egyptian artifacts might seem a topic beyond the scope of the War Office. But not when their top agent played the role of Bonaparte’s pet scholar.

When Richard created the Purple Gentian, the talent for ancient languages that had stunned his schoolmasters at Eton had come to his aid once again. While Sir Percy had pretended to be a fop, Richard bored the French into complacency with long lectures about antiquity. When Frenchmen demanded to know what he was doing in France, and Englishmen reproached him for fraternizing with the enemy, Richard opened his eyes wide and proclaimed, “But a scholar is a citizen of the world!” Then he quoted Greek at them. They usually didn’t ask again. Even Gaston Delaroche, the Assistant Minister of Police, who had sworn in blood to be avenged on the Purple Gentian and had the tenacity of . . . well, of Richard’s mother, had stopped snooping around Richard after being subjected to two particularly knotty passages from the Odyssey.

Bonaparte’s decision to invade Egypt had been a disaster for France but a triumph for Richard. He already had a reputation as a scholar and an antiquarian; who better to join the group of academics Bonaparte was bringing with him to Egypt? Under cover of antiquarian fervor, Richard had gathered more information about French activities than Egyptian antiquities. With Richard’s reports, the English had been able to destroy the French fleet and strand Bonaparte in Egypt for months.

Over those long months in Egypt, Richard became fast friends with Bonaparte’s stepson, Eugene de Beauharnais, a sunny, good-natured boy with a genius for friendship. When Eugene introduced Richard to Bonaparte, presenting him as a scholar of antiquities, Bonaparte had immediately engaged Richard in a long debate over Suetonius’s Lives of the Caesars. Impressed by Richard’s cool argument and immense store of quotations, he had extended an open invitation to drop by his tent and dispute the ancient past. Within a month, he had appointed Richard his director of Egyptian antiquities. Among the sands of the French camp in Egypt, it was a rather empty title. But on their return to Paris, Richard found himself with two rooms full of artifacts and an entrée into the palace. What spy could ask for more? And now his artifacts had been moved into the palace, Bonaparte’s lair. . . .

Miles looked as though he had been handed a pile of Christmas presents in July. “And your office with it?”

“And my office with it.”

“Damn it, Richard, this is brilliant! Brilliant!” Miles so forgot himself as to raise his voice above a whisper. Quite far above a whisper.

At the far end of the room, old Falconstone stirred. “Whaaat? Eh, what?”

“I quite agree,” Richard said loudly. “Wordsworth’s poetry is quite brilliant, but I shall always prefer Catullus.”

Miles cast him a dubious glance. “Wordsworth and Catullus?” he whispered.

“Look, you were the one who shouted,” cast back Richard. “I had to come up with something.”

“If it gets around that I’ve been reading Wordsworth, I’ll be booted out of my clubs. My mistress will disown me. My reputation will be ruined,” Miles hissed in exaggerated distress.

Meanwhile, Falconstone had staggered to his feet, and did a bizarre little dance as he tried to catch his balance with his cane. Spotting Richard across the room, his face darkened to match his burgundy waistcoat.

“Blasted cheek showing your face here! After you been consorting with them Frenchies, eh, what?” Falconstone roared with the complete lack of shame of the extremely deaf and the complete lack of grammar of the extremely inbred. “Blasted cheek, I say!” He tried to poke at Richard with his cane, but the effort proved too much for him, and he would have gone tumbling had Richard not steadied him.

Glowering, Falconstone yanked his arm away and stalked off, mumbling.

Miles had jumped to his feet when Falconstone had charged Richard. He looked at his friend with concern. “Do you get much of that?”

“Only from Falconstone. I really do have to get around to freeing his son from the Temple prison one of these days.” Richard resumed his seat and drained the remainder of his scotch in a single swallow. “Don’t be such an old woman, Miles. It doesn’t bother me. Look, I prefer Falconstone’s rantings to all those debutantes twittering about the Purple Gentian. Can you imagine what I’d have to put up with if the truth got out?”

Miles cocked his head thoughtfully, sending a lock of floppy blond hair tumbling in front of his eyes. “Hmm, adoring debutantes . . .”

“Think how jealous your mistress would be,” Richard said dryly.

Miles flinched. His current mistress was an opera singer as well known for the range of her throwing arm as that of her voice. He had already courted concussion by flirting openly with a ballet dancer and had no desire to repeat the experience. “All right, all right, point taken,” he said. “Oh, damnation! I promised her I would have supper with her before the opera. She’ll probably break half the dishes in the house if I’m late.”

“Most of them over your head,” commented Richard helpfully. “Since I prefer you with your head all in one piece, you’d better relay my assignment quickly.”

“How right you are!” Miles replied fervently. He struggled to collect himself and regain the gravity incumbent upon a representative of the War Office. “All right. Your assignment. We’re pretty sure that Bonaparte is using the peace to plot an invasion of England.”

Richard nodded grimly. “I thought as much.”

“Your job is to uncover as much as you can about his preparations. We want dates, locations, and numbers, as quickly as you can get them. We’ll have a string of couriers posted from Paris to Calais to relay the information as you find it. This is it, Richard!” Miles’s eyes glowed with sporting fervor, like a hound on the trail of a fox. “The assignment. We’re relying on you to keep old Boney out of England.”

A familiar tingle of anticipation rushed through Richard. How had Percy been able to give this up? The rush, the excitement, the challenge! Heady stuff, to know the safety of England depended upon him. Of course, Richard didn’t delude himself that he was the country’s sole hope. He knew the War Office had a good dozen spies scattered around the French capital, all striving to uncover the same things. But he also knew, without false modesty, that he was their best.

“The usual code, I suppose?” They had developed the code their first year at Eton as part of an elaborate plan to outwit their bullying proctor.

Miles nodded. “You’ll leave for Paris in two weeks?”

Richard rubbed his forehead. “Yes. I have some personal business to take care of—and I’ve promised my mother to squire Hen around to scare the fortune hunters away. Bonaparte should be away at Malmaison for most of next week, anyway, and I’ve left Geoff to keep an eye on things while I’m gone.”

“Good man, Geoff.” Miles rose and stretched. “Now if he were here, the three of us could have a bang-up night of carousing just like old times. I guess it’ll have to wait till we’ve foiled old Boney once and for all. Cry God for England, Harry, and St. George, and all that.” Miles was frantically trying to rearrange his cravat and smooth down his hair. “Damn. No time to stop off at home and get my valet to tidy me up. Oh well. Give Hen a kiss for me.”

Richard shot him a sharp look.

“On the cheek, man, on the cheek. God knows I’d never try anything improper with your sister. Not that she isn’t a beautiful girl and all that, it’s just, well, she’s your sister.”

Richard clapped his friend on the shoulder in approval. “Well said! That’s exactly the way I want you to think of her.”

Miles muttered something about being grateful that his sisters were a good deal older. “You turn into a complete bore when you’re chaperoning Hen, you know,” he grumbled.

Richard raised one eyebrow at Miles, a skill that had taken several months of practice in front of his mirror when he was twelve, but had been well worth the investment. “At least I didn’t let my sister dress me up in her petticoat when I was five.”

Miles’s jaw dropped. “Who told you about that?” he demanded indignantly.

Richard grinned. “I have my sources,” he said airily.

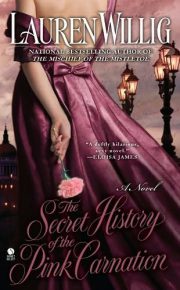

"The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" друзьям в соцсетях.